Cycling Globe to Sierra Vista, Arizona: Made it to the Mexican Border

28 September - 6 October 2021

Segment 9 of the Western Wildlands Bikepacking Route (270 miles, 435 km)

Monsoon Mists

Although hot, dry weather is the norm in Arizona, there is actually a rainy season. July to the middle of September is known as the monsoon season, when warm winds off of the Gulf of California bring most of the year’s precipitation to the American Southwest in the form of frequent afternoon rainstorms. Then things dry out. By the end of September, the probability of monsoon showers is usually pretty low.

That’s critical for planning, because virtually all the dirt and gravel roads in Arizona become impassible when wet. We were forewarned many times to avoid off-road cycling in this area after it rains. With that in mind, we had intentionally ridden the WWR at a pace that would delay our arrival in southern Arizona until late September, after the main threat of rain had passed - or so we thought.

It didn’t quite work out that way. Instead, 2021 was Arizona’s wettest monsoon season in seven years, including a near-record number of days with measurable rainfall - extending well into September. When we arrived in Globe, Arizona, we learned that the forecast included several days of sustained rain. So we settled in to wait out the storms. We ended up delaying our departure from Globe for three days.

When the weather finally cleared, we were itching to get back on the road. It had rained overnight, leaving a damp chill in the morning air. The forecast said there would be no more rain, but the sky still looked ominous. Low, gray clouds hung over the surrounding mountains, obscuring the scars left by a wildfire that had burned through the nearby national forest last June. Rows of Mediterranean Cypresses, one of southern Arizona’s most striking ornamental trees, sliced through the gloom with their dark, dagger-like silhouettes.

We hadn’t seen many of the tall, pointy Mediterranean Cypress trees before arriving in Globe. Then, suddenly, they were everywhere. Globe, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Moisture from the monsoon rains hung in the air, blanketing the surrounding mountains with low, wispy clouds. Tonto National Forest, Arizona Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

The local wildlife seemed to enjoy the cooler temperatures. As we headed southward into Tonto National Forest, birds flitted around us, darting across the road and scattering into the brush. We spotted several large flocks of quail, typically catching just a glimpse of their blue-gray backs as they flew away when we rode by. Fortunately, a few lingered long enough for us to enjoy watching them strut across the sand with their fancy, black-plumed hats.

But the star of the show was a big, furry spider. Over the years we’ve often heard about how easy it is to see tarantulas in Arizona. Yet even though we’ve spent a fair amount of time in the state, we’d never come across one - probably because we tended to visit in the springtime. It turns out that late-summer into fall is the best time for tarantula-spotting. That’s when the males venture out from their burrows to seek a mate. And south of Globe we met our first fellow out looking for romance - a Grand Canyon Black Tarantula. He was a fine specimen. We wished him luck in his search.

Echoes of a Wildfire

As soon as we began our ascent into the Pinal Mountains, we entered the area burned by the massive Telegraph Fire of 2021. It was one of the biggest fires ever recorded in the state. Just a few months before we arrived, throughout the month of June, the Pinal Mountains near Globe, Arizona were on fire. Nearly 200,000 acres (80,000 ha) of land were scorched - most of it within the Tonto National Forest. In fact, the reason we were even traveling on US Hwy 77, instead of on a remote dirt road, was because the official WWR route remained closed to recreation as a result of the Telegraph Fire. Rainwater quickly runs off of the burnt vegetation and layer of ash (instead of being absorbed by the soil). That creates dangerous conditions, even more prone to flash flooding than usual. So the backroads through the national forest remained closed, and would stay that way until the monsoon rains were no longer a threat.

Map of the area burned by the 2021 Telegraph Fire near Globe, Arizona. The fire burned nearly 200,000 acres (80,000 ha) before being brought under control in early July 2021. Image courtesy of Inciweb.NWCG.gov (National Wildfire Coordinating Group).

We saw ample evidence that flooding had recently been a problem, even along US Hwy 77. Fluorescent orange traffic cones lined portions of the highway where rushing water had swept through roadside ditches, leaving deep gullies. In some places, the erosion was so bad that dirt had washed away from under the road. Fortunately the traffic was light, because occasionally we had to ride in the center of the traffic lane to avoid spots where the asphalt was crumbling away into the trenches below.

For 12 miles (19.5 km) we cycled through the Telegraph Fire burn area. It was good to see that life was rebounding there, in response to the monsoon rains. Grasses and other short, brushy plants were growing in thick, green clumps. Quite a few of the cacti seemed to have survived the fire as well. But the bigger bushes and trees were charred and blackened, with their leafless limbs silhouetted against the hills.

The Telegraph fire in Arizona’s Pinal Mountains was one of the largest in the state’s history. A number of surrounding communities were evacuated, and 51 structures were burned. Fortunately there were no human casualties. Tonto National Forest, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

When we reached the top of Pinal Pass, we were ready for a short break. A small picnic area just before the crest of the ridge offered the perfect opportunity for a rest stop, with a grandly scenic view across a v-shaped canyon. The grass-covered slopes were still dotted with the ghostly forms of scorched trees. And the thick gray clouds that had haunted us all morning still cast their shadow over a distant mountain. But the clouds were beginning to dwindle. Overhead, the sun was already peeking through, casting a warm glow on the nearby hills.

Refreshed by our break, we sailed through the pass in a matter of minutes. What greeted us on the other side was a valley starkly different from the open fields and undulating slopes we had just climbed. Over the next 15 miles (24 km) we plummeted 3,000 ft (915 m) downward through rocky canyons capped with sheer cliffs. Multiple road signs warned truckers to check their brakes before negotiating the steep gradients with tight curves. Other signs helpfully pointed out places where motorists could pull off the road to let their brakes cool, or where runaway trucks could plow into piles of sand if their brakes failed.

The southern slopes of the Pinal Mountains were carved by rugged, stony canyons, capped by sheer cliffs. For cyclists, the descent on US Hwy 77 is fast and fun, but also a bit challenging because of a narrow road shoulder. Pinal Mountains, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

It didn't help that the road’s shoulder, which had been nice and wide most of the way uphill, had narrowed considerably. It was basically useless for cycling downhill at high speeds - causing us to ride most of the way in the primary traffic lane. With our senses on heightened alert, we kept one eye on our rearview mirrors for fast-moving vehicles approaching from behind, and the other ahead to avoid colliding with any cars or trucks that might swing wide while coming around a turn. Fortunately, the miles flew by as we sped downhill at 35-45 mph. In less than an hour we reached the wide Gila River Valley, where we cycled over more moderate terrain towards the town of Winkelman. Just before reaching the valley, we re-joined the official WWR route, thus completing the Telegraph Fire detour.

Another Encounter with the Arizona Trail

By the time we reached Winkelman, Arizona, we were missing the cloudy skies that kept us cool all morning. The bright afternoon sun had burned off most of the cloud cover, just in time for us to reach the lowest elevation of the day’s ride. Winkelman sits in a deep valley at the confluence of the Gila and San Pedro Rivers, so most roads out of town require heading uphill. And the WWR route will always steer towards the highest mountains it can find. That meant we were facing a 2,300 ft (700 m) climb, with virtually no shade, just as the temperature was pushing into the low 90s F (33+ C). We stopped at the convenience store in Winkelman to savor one, last cold drink. Then we pedaled out of town to tackle the next mountain pass.

Just outside of Winkelman the WWR route leaves Hwy 77 behind, to ford the San Pedro River on a gravel road. There’s no bridge, so the WWR route information duly warns cyclists not to cross the river if it’s flowing strongly. That wasn’t a problem for us - there was just a trickle of water in the river. More disconcerting was the fact that there were “Private Property, No Trespassing” signs at the entrance to the dirt road that implied using the road could get you in trouble. Private property rights are taken very seriously in rural Western communities, and you don’t want to have an encounter with an angry property owner. So, we were unsure at first whether we should proceed.

But after double-and-triple-checking our route map, we were sure that the WWR followed this road. Furthermore, a recent conversation we had with a lawyer in Idaho who works on western land issues reminded us that landowners can sometimes get overzealous with posting their property, blocking what should be public rights-of-way.

We talked ourselves into believing that the signs meant you shouldn’t enter the land on either side of the road, but that traveling on the road must be okay (even though the signs looked like they applied to using the road). And so we headed towards the San Pedro River crossing. Even so, we continued to have misgivings and hustled through as fast as we could. The map showed that this road would connect with another paved road in 0.5 miles, and we hoped to make it to the other side without encountering anyone.

Still, you can only go so fast through sloppy mud. Our hearts sank when we heard a truck approaching from the other direction while we were still pedaling slowly up the far bank of the river. As it rumbled into sight ahead of us, we braced ourselves for the possibility that we would have to talk our way out of a sticky situation. We both let out a big sigh of relief when the truck passed us by. The driver was more focused on finding the least bumpy path through the jumble of rocks and mud than worrying about a couple of crazy cyclists.

From there it was all uphill. We had the benefit of a couple of miles on a paved road, but before long we were back on the gravel. For the rest of the day we would cycle on dirt roads through a patchwork of private and state-owned lands.

These are “working lands,” which the state uses to raise revenue through grazing and agricultural leases (usually to neighboring landowners). As such, they don’t have any of the amenities you might expect at a state park. Moreover, members of the general public are not allowed to cycle, camp, hike or otherwise use the property without first obtaining a recreational permit from the state. A roadside sign prominently reminded travelers of the permit requirement. Luckily, these permits are easy to obtain online, and we had purchased ours before entering the state. So we were good to go.

A sign like this one alerted us that we were about to enter Arizona state trust lands. Fortunately, we had purchased our recreational use permit before entering the state. Tortilla Mountains, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Although there weren’t any trees that could provide shade for hot and sweaty cyclists, there were still some interesting plants. The vegetation in the Sonoran Desert has an incredible variety of shapes and forms, unlike the shade-deprived sagebrush landscapes that we had ridden through farther north - where nothing seemed to grow more than a couple of feet high. There were plenty of tall plants, and even a few rugged trees. Most of them don’t cast much of a shadow because they are either leafless, or their leaves are very tiny. But the real kicker is their thorny defenses. Every single one comes bristling with skin-piercing needles or dagger-like spines. There’s no shade to be had under a barbed mesquite tree that has a bed of prickly-pear cacti surrounding its trunk.

Still, we couldn’t help but be impressed by the myriad of trees and tree-like plants that look so foreign to folks like us, not raised in the desert. In addition to the majestic saguaros and spindly ocotillos, there were jumping chollas (so named because if you even get close to them, a piece of the stem will break off, clinging to your clothing by it’s fishhook-barbed spines) and the eerily green palo verde (Arizona’s state tree).

As the afternoon wore on, we started looking for a place to camp. But try as we might, we couldn’t find any sites that wouldn’t put us and our gear at risk of multiple puncture wounds from the myriad variety of spines. It’s always a bit of a gamble when wild camping, and we started to worry that this time we might lose the bet. It can be surprisingly difficult to find a campsite in places no one has ever camped. Rocks, spines, flash flood areas, dense vegetation, dead snags, uneven ground, wind, and sharp lava rocks (just to name a few), are all things that have provided campsite challenges on this trip.

Then we got lucky. Ahead of us we saw a large, level, gravel parking area. It was a trailhead where the Arizona Trail (AZT) crossed our route. We hadn’t seen the AZT since our adventure just north of Flagstaff, and didn’t realize we’d be crossing paths again. But this turned out to be just the break we were looking for. We parked our bikes and walked up and down the trail for a short distance in both directions, hoping that hikers might have cleared a campsite nearby. Unfortunately, there still weren’t any good spots big enough for our tent.

It didn’t matter in the end. The parking lot itself turned out to be a great spot to camp. It was spacious, level, and thorn-free. We pitched our tent close to the vegetation on the far side of the lot, away from the road. Desert birds serenaded us at dusk, and only one car passed by during the entire time we were there. The autumn sun set fairly early, glowing a hazy red as it edged towards the horizon around 6pm. The image was captivating.

No, it’s not the planet Jupiter or one of Tatooine’s setting suns. It’s a desert sunset in a remote corner of Arizona. Tortilla Mountains, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

After sunset, we set up our sleeping bags in the dark. Once again we decided to pitch just the mesh inner tent. But unlike the last time, when our view was obscured by a forest of ponderosa pines, we now had a sweeping view of the night sky. The waning moon wouldn’t rise until after 11pm, so the stars shown in all their glory. We laid there for a while, gazing upwards. The Milky Way was a bright river of light. We even saw a few shooting stars before drifting off to sleep.

Even though no cars drove by in the dark, it was not exactly quiet. A couple of great horned owls hooted on-and-off all through the night. It seemed odd to us that such a large owl would hang out where there were no tall trees. Yet it seems that great horned owls are one of the most common owls in the desert. In addition, there was a pack of coyotes that went into fits of communal yapping half a dozen times. It made for a fitful night’s sleep.

Remember to Keep Drinking

The air was surprisingly humid in the morning, considering we were in one of the driest parts of the country. When we awoke, anything that was exposed to the air inside the tent was damp. That’s definitely one of the downsides of sleeping without a waterproof cover. Our clothes, packs and sleeping bags were all coated with a thin sheen of moisture. Hoping that they would dry quickly in the desert sun, we waited until after sunrise before getting out of bed. But the air was still quite humid. We had a fairly long day of cycling ahead, so we packed up our wet gear with the plan to air it out later.

Right out of camp the route continued its uphill trajectory. For the next nine miles (15 km) we ground our way up to the top of the ridge. Along the way, the desert’s fascinating plants and animals continued to surprise and delight us.

Soaptree yucca was one of our favorite desert plants. This shaggy giant was over 10 ft (3 m) tall (not including the flower stalks). Tortilla Mountains, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the way we spotted this beauty - a Desert Blonde Tarantula. Seeing tarantulas march across the road never gets old. Tortilla Mountains, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

From the top of the ridge we could see our destination, the town of Oracle (pop. 3,600) nestled on the far slopes of the Pinal Mountains. It was still more than 20 miles (32 km) away, on the opposite side of a broad, dry valley. And as a consequence of our later-than-usual start, the temperature was rising fast.

We knew the last few miles of the ride would be on pavement, easing the difficulty of the final climb into town. So we figured we’d push on through as quickly as we could. Our hope was to arrive in Oracle before the afternoon got too hot. With a 10 mile drop before the final ascent, that seemed doable. We headed downhill, setting a fast pace.

Unfortunately, with our single-minded focus on getting to the end as quickly as possible, we forgot a fundamental rule of cycling in the desert - to drink plenty and often. We’re particularly susceptible to not taking in enough liquids when there’s a long downhill section. It’s just easier to keep going than to stop and take a drink. And when you’re cycling down a bumpy, off-road descent, you’re unlikely to reach for your water bottle while riding because taking your focus off the road and your hand off of the handlebars can be risky. As a result, we didn’t drink enough and didn’t stop for any breaks until quite late in the day.

When we finally dragged ourselves into town, we were both a bit dehydrated. Of course, we stopped at the first opportunity and guzzled down some chocolate milk and gatorade. That helped a lot. But then we made another critical error. We couldn’t remember if our hotel room had a refrigerator, so we opted not to buy some extra fluids to take with us. That was unfortunate, because the only hotel in town was more than a mile from any place where you could buy food or drinks. The end result was that we didn’t drink enough after checking into the hotel, while taking care of essential business like showers and laundry.

By the time we finished our chores we were dehydrated again. We had to force ourselves to find the energy to walk the two miles, round trip, to the closest convenience store for some provisions. After lugging it all back to our room, we finally were able to focus on resting, eating and drinking. It made a big difference, but we both still felt a bit weak and cranky. Before heading to bed, we decided to take a rest day in Oracle to recuperate.

A Bit of California in Arizona

Oracle, Arizona has a laid-back charm reminiscent of small towns in California. One of the first things you notice when traveling along the main thoroughfare, American Avenue, is the prevalence of home-grown art and antique shops. The sign outside the Oracle Visitors’ Center proudly announces that they have pieces for sale by local artists. But one could just as easily stop to browse in half a dozen other art boutiques, galleries and trading posts that overflow with quirky, desert-themed artwork.

We really felt like we had been transported to California when we went out for breakfast at the Oracle Patio Cafe. Seated on a back patio covered by a wooden trellis and nestled among stone walls, we selected from a menu of made-to-order dishes with a heavy emphasis on ultra-fresh, and often unusual ingredients (daikon radish sprouts, anyone?). Of course, the condiments on the table included coarse-ground, pink sea salt and organic peppercorns. Although it seemed a bit pretentious compared to the small town, mom-and-pop diners we had become accustomed to, we had to admit that the large portions were delicious - and just the thing we needed to help restore our energy. We would recommend the Cafe to anyone passing through Oracle.

Back at the hotel, PedalingGuy noticed a sheen of dark oil on several components of his back wheel hub. A closer inspection revealed that a small amount of oil had leaked out of his Rohloff Speedhub. Our natural reaction was to worry that something was wrong, especially since we had changed the oil in our hubs for the first time not that long ago. PedalingGuy cleaned off the oil, checked to ensure that the drain screw was tight, and visually inspected the other seals. Everything looked okay. Rohloff says that it’s not a problem if a bit of oil leaks out, because only a small amount is needed for proper operation of the gears. So, we decided not to worry about it unless the problem continued (it has not).

It’s always disconcerting when one of your components leaks oil. But a visual inspection of PedalingGuy’s Rohloff Speedhub didn’t reveal any obvious problems. So we decided not to worry about it. Oracle, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

El Rancho Robles, where we stayed in Oracle, bills itself as a “guest ranch.” It was built in the 1920s as a dude ranch, where city folks could ride horses and have a “western” experience. These days, guests can camp or rest in one of the hotel-style rooms in a remodeled ranch building (e.g., the stables where we stayed). The property is old enough that the trees and other landscaping are quite mature, which seems to attract quite a lot of wildlife. We spent part of the evening strolling around the grounds, looking for wildlife, and enjoying the tranquil setting.

Visiting with a very big American Century Plant. El Rancho Robles, Oracle, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Muddy Waters in the Desert

In less than 40 minutes after departing from Oracle, we cycled over the ridge that separates the town from the broad, scenic San Pedro River Valley. The San Pedro River is special for a number of reasons, including the fact that it is the longest remaining, free-flowing desert river in the USA. For much of its length, water still courses through its channels year-round. This anchors a complex ecosystem including a tree-lined riparian corridor that winds across desert plains, bordered by 9,000 ft (2,750 m) tall mountains. An astonishing 2/3 of the regularly-occurring species of birds in the USA use the San Pedro River Valley as either breeding habitat or a migration corridor.

We cruised down a fairly gentle slope on a quiet road, to a plateau overlooking the valley. There, in the town of San Manuel, we treated ourselves to a quick breakfast before completing the descent to the river itself. The final 700 ft drop into the valley was beautiful. We cycled through forests of saguaros towards the green ribbon of mesquite trees that lined the riverbanks, with the cliffs and slopes of the Galiuro Mountain Range in the distance.

For the rest of the day we followed the San Pedro River upstream. The route profile in our navigation software made it look like we would be cycling up a very gentle grade. But in reality, that moderate slope was virtually unnoticeable. It was completely overwhelmed by the wild undulations of the road as it careened up and down over small ridges that separated deeply eroded desert washes. It seemed as though every 10 minutes we were warned by signs not to cross the next wash if it was flooded. Fortunately, they were all dry. It was also helpful that the gravel road surface was pretty good for cycling. As a result, we were able to gain enough momentum charging down each precipitous hill to make it at least half-way up the subsequent, steep embankment. That made the roller-coaster ride a bit easier to handle.

During the monsoons, desert washes can become treacherous with fast-rising water. Each arroyo came with a sign warning travelers of the danger. Fortunately, all were dry when we passed through. San Pedro River Valley, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

For the next 40 miles (65 km) we pedaled up and down across those washes, within the broad San Pedro River floodplain. But the river itself was rarely in sight. Instead, we hugged the margins of the riparian area. Often the road was out in the open desert where there was no shade, a short distance from the river’s mesquite and willow fringe. But as the day progressed, the trees along the river grew bigger, and the road spent more time in the shadows. There were even a few stretches where there was quite a bit of shade from big, old mesquite trees. Every moment spent cycling in the shadows was bliss, and it helped keep up our energy well into the hot afternoon.

When we did see the San Pedro River, usually from the top of a bridge over the main channel, it looked like a river of chocolate milk - and not just because we were thirsty. The water was laden with brown sediment, probably churned up by recent rains.

A rare sighting of the muddy San Pedro River, from a bridge. San Pedro River Valley, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

We’d stop periodically to marvel at the natural wonders along the way. During one break, a white-lined sphinx moth hovered around PedalingGal’s bike for more than a minute, checking out her brightly colored straps and panniers. Red seemed to be its favorite color. Later, we spotted one of the few cactus flowers we’ve seen this year. The peak season for cactus blossoms is from April to June, so we were fortunate to come upon one so late in the year.

When we saw this giant, we just had to stop for one more saguaro photo. San Pedro River Valley, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

A Community’s Kindness

Given the hot and harsh conditions, the 60 mile (97 km) stretch of isolated gravel road between San Manuel and Benson, Arizona ordinarily would have required us to haul as much as 19 L (appx. 42 lbs) of water. But the thoughtfulness of one rural community made that unnecessary. We were able to carry much less water because half way between San Manuel and Benson lies the Cascabel Community Center. And they have made sure cyclists know about the facility, and feel welcome to stop there for water and a rest in the shade.

The center is not visible from the dirt road we were on, because it sits out of view on top of a steep hill, with a helicopter landing pad (most likely used for medical evacuations). What’s more, there isn’t actually a town nearby, just some widely dispersed ranches. There are no other buildings within sight. It seemed like a community center without a community. In effect, the community center serves people scattered over a large, sparsely-populated geographic area (unlike most community centers we were familiar with, which are usually in towns).

Since we were expecting a few homes nearby instead of an isolated building, we accidentally rode a short distance past the community center before realizing our mistake, and turning around. But after locating the turn and pushing our bikes up a steep embankment, we found our oasis. In the heat of the afternoon, we rested at a picnic table in the shade, drank several liters of water from the center’s spigot, and snacked on some gorp. It was very refreshing. The water wasn’t cold, but it was cool enough - way better than the water in our bottles that had been baked by the desert sun. When we were finished, we filled up our water bottles with another six liters, and headed back down to the dirt road we had been following. We didn’t see a single other person while we were there.

Warm thanks to the community of Cascabel, Arizona, for sharing their community center with cyclists passing through on this remote stretch of road. Cascabel, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Once we passed Cascabel, we started to see a few more cars and the road surface got a lot worse for cycling. The smooth, hard-packed dirt we had enjoyed since leaving San Manuel changed into a continuous series of washboards. That slowed our pace significantly.

Then we hit another snag. We had planned to ride 8.5 miles (13.7 km) further up the road to reach a stretch of Arizona State Lands where we could camp. But when we got there, both sides of the road were lined with barbed wire fences - presumably because these lands were being used for grazing, and they wanted to keep the cows off the road. We didn’t see any gates in the fence that would allow us to pass through, or to find a place to camp. We would have to bike another five miles (8 km) before reaching the next patch of public land. If that land was also fenced off, we faced the prospect of having to cycle all the way to Benson, Arizona for the night. The town was still many miles away, and we’d almost certainly arrive there after dark - not something we were looking forward to.

Around 52 miles (84 km) into our ride, we finally saw a gate in the fence. Even better, it was posted with an Arizona State Lands sign. A recreational use permit was required to camp there, but we had obtained one before entering the state, so no worries.

There was a decent camping spot close to the main road, but we thought it would be preferable to be farther away. So we hiked a long way up the dirt side road looking for something better. We couldn’t find anything. There were no cleared campsites, and all of the natural clearings either had a lot of animal dung (cows and sheep), had cacti too close for comfort, or looked like they were prone to flooding (there was a dry wash nearby). Even where dispersed camping is allowed, it is often very difficult to find a camping spot on public land. Having a rather large tent like ours makes it all the more difficult. After a while we decided that being down by the main road wouldn’t be so bad, after all.

In the end we were happy with our decision. Our main concern had been that we’d have to listen to noisy traffic, or deal with dust from cars passing on the dirt side road. But only one car passed us on the gravel around sunset. And shortly after that we stopped hearing any cars out on the main road. It was a totally peaceful night.

Because we had to ride so far from Oracle to find this campsite, we ended up having a very short ride the next day. It would be a quick, 16 mile (26 km) jaunt into Benson. That turned out to be a good thing.

When we woke up in the morning, everything in the tent was soaking wet - much wetter than our last damp camp. Even though it didn’t rain, the air was full of moisture. You’d think we would have gotten wise to this by now, but it seemed counter intuitive to us. For the first few months of the trip the mornings were always dry. But now that we were in the desert, there was a lot of dew.

Since it had been our last night of camping for the trip, and since it was fun to see the stars, feel the breeze, and possibly see any animals that might come close in the night, we had decided to pitch just the inner tent again and brave the morning dew. The downside, of course, was that our sleeping bags, pads, pillows, clothing and gear were now all sopping wet. We had a bit of a mobile phone signal, and the weather app said that the humidity was 84%! Not what we were expecting in the desert.

Fortunately, we had time to spare. So even though we were conditioned to wake up at first light, we laid in our warm sleeping bags waiting for the sun to dry things out. It took quite a while, but eventually our stuff was dry enough to pack. We finally hit the road a little bit after 10am.

Finally dry enough to pack. Even though we were in the desert, the humidity reached 84% during the night, soaking all of our gear with a heavy dew. San Pedro River Valley, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

The ride into Benson, Arizona was fast, pleasant, and relatively uneventful. We did get a kick out of crossing Tumbleweed Lane (our bikes are Tumbleweed Prospectors).

A bunch of Tumbleweeds, on Tumbleweed Lane. Benson, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Fissures, Fences and Fairbank

What a day. Well, actually, the first hour or so was a piece of cake. Then we hit the dirt.

Pretty soon we got our first signal that things could get tricky. A road sign had an ominous message we had never seen before: “Earth Fissures Possible.” What?! We weren’t sure exactly what to make of that sign. No “earth fissures” were visible at the moment. But we certainly wondered what might be in store for us down the road.

A road sign like this does not inspire confidence. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

At about 12 miles into the ride we hit our first obstacle. It wasn’t a fissure, but a fence. We had just entered the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, and the road we were traveling on came to a dead end at a locked gate. The site is actually a parking area for people visiting the St. David Cienega - a remnant wetland that is said to represent what most of the valley would have looked like before settlers trapped out all the beaver and channelized the San Pedro River in the 1800s. Unfortunately, you can’t see the cienega from the parking area. It lies half a mile away, obscured by surrounding shrubs.

Our primary concern, though, was how we would get our bikes to the other side of the barrier. It wasn’t immediately obvious. We walked back and forth along the road a number of times, looking for a break in the barbed wire fence. But we couldn’t find any. We were beginning to think that we would have to lift our bikes over. But before tackling that unpleasant task, we decided to walk over and read an informational sign about the cienega, posted further down in the parking lot. As we got close to the sign, PedalingGuy spotted a break in the metal fence, hidden behind a bush. We happily pushed our bikes through.

We almost missed this break in the fence, hidden behind a bush. St. David Cienega, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Beyond that fence, the road conditions deteriorated quickly. The next 3.7 miles (6 km) were some of the toughest cycling of the day. The WWR materials refer to this stretch as a 4x4 track, but it’s really just an unmaintained maintenance track for a gas pipeline. And it was riddled with fissures of all sizes. There were small, narrow gullies that tried to grab our tires as we rode by. And there were massive erosional cuts that had washed away whole sections of the road. Most of the hills were very steep and strewn with rocks. It took us nearly two hours to maneuver our way through this obstacle course.

Picking our way through an obstacle course of “earth fissures,” both small and large. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

At this point, the road had completely washed away, with a chest-high cliff of sand on the far side. We had to push our bikes up a short-but-steep, brush-covered hill, two people per bike, to get them back on the road. California Wash, San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

One of the hills was so long and steep, with a loose surface, that we had to push our bikes up one at a time.

Things improved a bit when we reached the end of the 4x4 track. The next section of the route followed an old railroad grade. But this was no well-groomed rail trail, and it presented its own set of challenges. The gravel was loose and mushy, dragging at our tires. And the trail was overgrown with mesquite and creosote bushes. We had to constantly weave back and forth, slipping in the loose gravel, to avoid getting impaled on the thorny branches that reached out to scratch us. At least the railroad grade had bridges across the fissures, which by this time had become mini canyons.

We were lucky there was a bridge over this mini canyon. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the railroad route, we stopped to take a look at some ruins from an old Spanish land-grant, the Boquillas Ranch. This was not the main townsite of the ranch (which was further south). But the crumbling brick walls were still impressive. Every room seemed to have it’s own fireplace, which helped to date the building from before electric and gas heat found its way into the region. The break also gave us a chance to shake the sand out of our shoes, and brush off the dozens of burrs that were clinging to our socks and shoes.

Just up the trail from the Boquillas ranch, we came to another locked fence. It really was perplexing that these gates were all locked. A sign posted on the fence made it clear that the trail was intended for use by bikes and horses, in addition to hikers. But there was no way to get through this time. We had to unload our gear and lift our bikes over the gate. That’s certainly a pain for cyclists. But what would someone on horseback do? For all practical purposes, they wouldn’t really be able to use the trail.

Beyond the gate, the trail became even more overgrown with vegetation. All of these trees were covered with thorns. We had to gingerly maneuver our bikes through the gauntlet. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Try as we might, we weren’t able to avoid a few casualties from the thorn bushes and sharp rocks. Within a few minutes of leaving the Boquillas Ranch ruins, sealant began to spew out of a hole in PedalingGuy’s back tire. He tried rolling the damaged part of the tire in loose dirt to block the leak, but to no avail. PedalingGuy ended up with punctures in both his front and back tires that were serious enough to require Dynaplugs to stop the air from escaping. PedalingGal also sprung a leak in one of her tires, but fortunately the sealant was enough to plug the hole. We marked all of the punctures with a Sharpie pen so we could keep an eye on them, and perform additional repairs later if needed.

Just when we thought we’d already had plenty of excitement for the day, we were surprised and somewhat amused to see a double-line of massive boulders creating a barrier across the trail. In addition to the boulders, there were lines of metal fence posts that were spaced too close to each other for our handlebars to fit through. We had to lift each bike over the rocks and bars, one at a time. At least we didn’t have to remove the panniers this time. Perhaps this wouldn’t be that much of an obstacle for riders on unloaded bicycles. But it sure was a headache for us. And it called into question the sincerity or competence of the trail managers in calling this a horse path. Presumably these barriers are meant to keep out motorized vehicles. But they would be pretty effective in stopping most uses other than hiking. Perhaps that is why the trail was so overgrown.

There’s no doubt about it. This section of the WWR was a challenge. And it was frustrating that many of the obstacles could have been avoided by better fence designs. When we finally reached the final gate, where the San Pedro Trail ended at a paved road, we had covered only 9 miles (14.5 km) in 4.5 hours.

But we don’t want to leave the impression that we regret the ride. Even though it was slow going, we were in no hurry. There weren’t any insurmountable obstacles. Moreover, the scenery was dramatically beautiful - a broad, arid valley bordered by rugged mountains, under a picture-perfect, blue sky studded with puffy, white clouds. Once we passed the first locked gate back at St. David’s Cienega, we didn’t see another soul for nearly five hours. Whenever we stopped to catch our breath, we remembered what a joy it was to be there.

The Dragoon Mountains provided a dramatically beautiful backdrop to our ride. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Of course, there was one final gate to negotiate when we reached the end of the trail at North Kellar Road. Fortunately, there wasn’t any lifting involved. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

North Kellar Road Trailhead of the San Pedro Trail. San Pedro Valley, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

It was after 2pm by the time we pushed our bikes out of the National Conservation Area, and onto a wide gravel road. Fortunately we had only 13 miles (21 km) to go before reaching our destination for the night. We headed down the road, eager to make tracks after our slow progress earlier in the day.

However, we did make one, final stop. The route passed by the ghost town of Fairbank, Arizona, and we decided to have a look. Located about 0.25 miles down a gravel side road, Fairbank was quite different from other ghost towns we had visited up in Idaho and Montana. Those northern towns were typically occupied for less than 50 years, and the buildings had the look of temporary structures (often log cabins). But people lived in Fairbank for nearly 100 years, with a few residents still present as late as the 1970s. For the most part, the buildings are pretty substantial, like the schoolhouse built of locally-quarried stone. In fact, it looks remarkably similar to a lot of tiny, rural towns - just without the people. On the other hand, the informational signs posted outside each building are a potent reminder that this town is now a museum.

We were both hot and tired when we reached Fairbank. So it was wonderful to take a break at a picnic table for visitors, tucked in a shady grove of trees. Drinking water was available from a spigot nearby, and it was just the thing to help boost our energy for the remainder of the ride.

Re-Living the Old West

Tombstone, Arizona has an infamous reputation, arising from its wild days as a gold-rush town. But rather than shun its lawless past, Tombstone has heartily embraced it. The tone is set as you approach town, where a billboard reminds you that Tombstone is the site of the O.K. Corral. Anyone familiar with western lore has heard of the corral, where the three Earp brothers (including Wyatt Earp, of course) and Doc Holliday got into a deadly gunfight with a gang of local outlaws. “Gunfight Daily!” proclaims the billboard. And the message is accentuated by the image of four mustached cowboys pointing their guns directly at you.

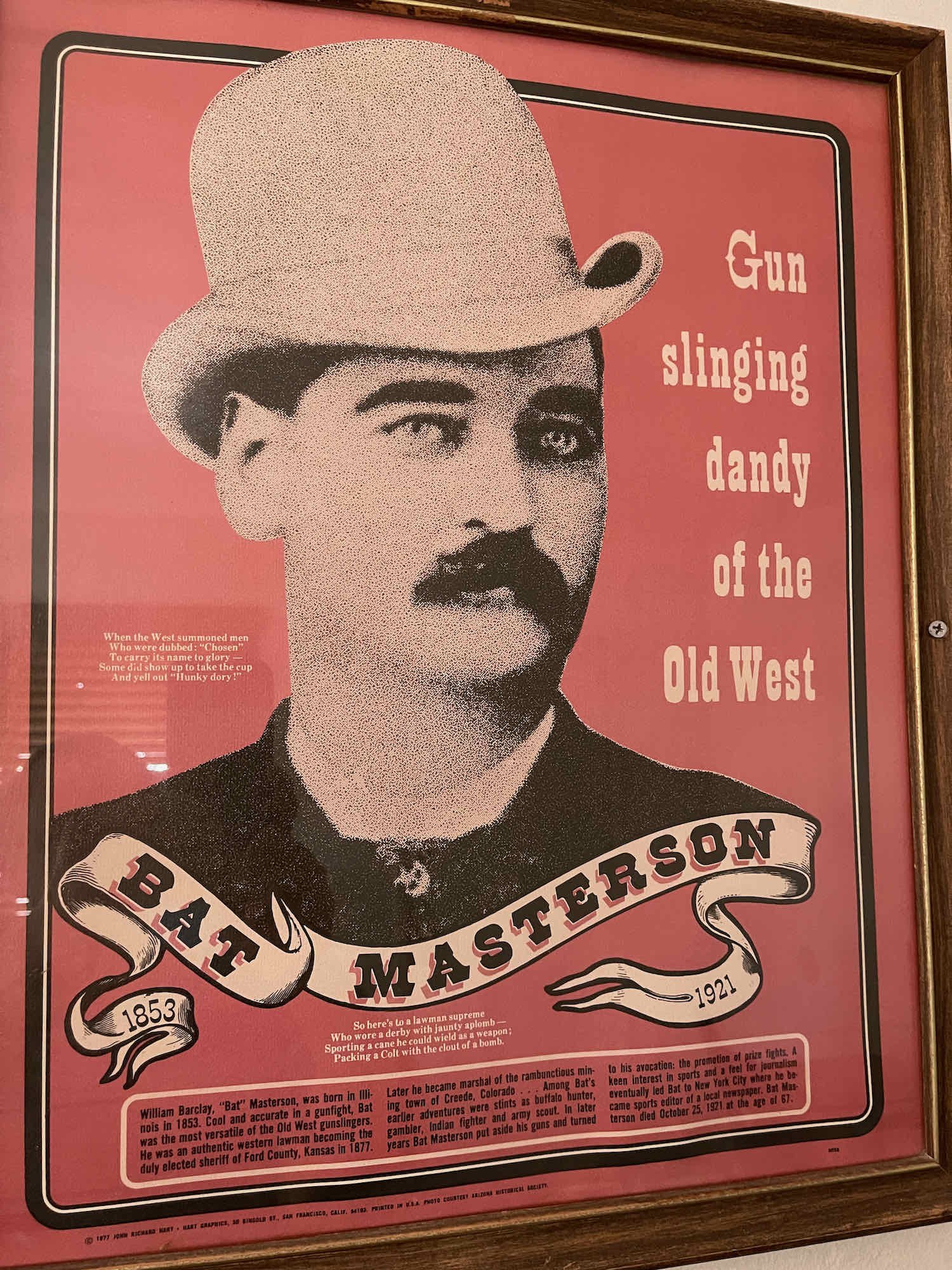

Everything about Tombstone celebrates the Wild West era. At our hotel, each room was named for a famous gunslinger. We stayed in the Bat Masterson room (Mr. Masterson was a friend and fellow-lawman of the Earps). Many of the buildings in town are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. And the ambiance of wooden sidewalks lined with lovingly-restored storefronts, populated by folks in leather vests and riding boots, and the occasional side-arm, can almost make you feel like you’ve been transported back 140 years. Although there are some actors who reenact the the O.K. Corral shootout, many of the people you see are local residents or visitors who break out their western gear and hand guns when they come to town.

Tombstone’s two main streets have been restored to evoke the town’s gold-rush glory days. Tombstone, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Colorful personalities from the Wild West are frequently invoked by local businesses. You can visit Wyatt Earp’s Oriental Saloon, where the famous lawman once owned a share of the gambling tables. There’s also Doc Holliay’s Saloon and Big Nose Kate’s Saloon - neither of which were actually ever connected with their namesakes. (Big Nose Kate was Doc Holliday’s companion). And the 1993 movie Tombstone can be seen playing on big-screen TVs in many restaurants and bars. If you enjoy Western cowboy icons and culture, this is your town.

Dinner in Big Nose Kate’s Saloon is an experience steeped in Old West symbolism. You can even watch the 1993 movie named after the town on a big-screen TV while you eat. Tombstone, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

A Quick Stop at the San Pedro River

We had decided a while ago that we wanted to avoid camping too close to the US-Mexico border. This year has seen record numbers of illegal crossings from Mexico, making the border region even more sketchy than usual. And in the past we’ve seen enough questionable activity along remote stretches of the border on other trips, that it just seemed prudent to limit our exposure at night.

As a result, we cycled straight to Sierra Vista from Tombstone, rather than heading directly for the border on the WWR. That way, we could ride to the Mexican border by following a loop out of Sierra Vista that could be completed in a single day (avoiding the need to camp). Since the ride between Tombstone and Sierra Vista was only 19 miles (30.5 km), that left us plenty of time to stop for some gallery-forest birding along the San Pedro River - which lies about halfway between the two towns.

This crossing of the San Pedro River was about 70 miles further upstream (to the south) than our previous crossing, north of Cascabel. And, wow, the river had changed. Here, the banks were lined with tall cottonwood trees and the water was almost clear. The shaded paths along the river looked very inviting compared to the surrounding desert.

Cottonwood gallery forests line the upper San Pedro River. We couldn’t resist the urge to go down and walk among the shadows along the riverbank. San Pedro River, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

An abandoned bridge over the river provided a convenient place to lock our bikes. San Pedro River, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

A nice variety of forest birds, like this Red-naped Sapsucker, were hanging out in the cottonwoods. San Pedro River, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

We enjoyed a pleasant stroll among the stately trees. But it wasn't too long before we started to worry about finishing our ride before the afternoon heat set in. So, we headed back to our bikes, and pedaled the remaining miles to Sierra Vista.

A big flock of Gambell’s Quail lived in an undeveloped lot next door to our hotel in Sierra Vista. Each morning the dapper birds would sneak through the hotel’s parking lot, hunting for food along a fence line. We got a big kick out of seeing them each day. Sierra Vista, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Made it to Mexico!

Sierra Vista, Arizona is less than 20 miles (32 km) from the US-Mexico border, as the crow flies. But the WWR takes a slightly longer path. Since we would be returning to the same hotel in Sierra Vista that night, we had the luxury of leaving most of our gear behind, and taking only the essential items we would need for a day’s ride. Our bikes felt incredibly light and responsive when we headed out the door. It was the first time in months we had been on them without being loaded down with all our gear.

Once again, we rode towards the San Pedro River. Following a 50-mile (80.5 km) loop, we pedaled southward on quiet gravel roads, past widely-spaced ranch homes. There was even an alpaca ranch. And you could tell from some of the roadside signs, that folks in these communities relied on each other to get things done.

Our final run for the border would follow the San Pedro Trail, from the Palominas Trailhead. Not far from a new sign that marked the trailhead, a shriveled up, old sign warned us that illegal activities like smuggling were common in the area. It made us feel glad that we wouldn’t need to camp nearby.

We reached the Palominas Trailhead on a gorgeous, cloudless morning. The 9,500 foot high Huachuca Mountains made for a stunning backdrop to our ride. San Pedro Trail, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

From the Palominas Trailhead it was just four miles (6.5 km) to the edge of the United States. How hard could it be? We were about to find out.

The trail was bumpy, but mostly rideable for the first two miles. The biggest headache was that road repairs had been made in several spots using gravel that was either in really big chunks (about the size of a tennis ball), or really deep and squishy. There was also one large, dry arroyo with a very soft, sandy bottom that bogged us down even with our big tires. We had to push our bikes for about 50 yards (50 m) to get across the deep sand.

But those were minor annoyances. Once we passed a border patrol watch tower, while wondering if any border petrol agents would come out and ask us what we were up to, things got a bit trickier. The trail started to get more overgrown.

It turns out that the amount of vegetation, especially tall grasses, is correlated with the annual rainfall, which was at record levels this year. Thorny mesquite trees reached out across the trail, trying to snag our clothes and scratch us - causing us to weave back and forth to save our skin. Then, with about a mile to go, the vegetation took over completely. Dense grasses that grew taller than our heads covered the path so thoroughly that at times we couldn’t even find the road surface we were trying to ride on. We had to choose between just plowing ahead with limited visibility, or walking our bikes. In the end, we did a bit of both.

The thorny mesquite trees were still out to get us. We had to weave back and forth on the trail to avoid getting snagged by their outstretched limbs. San Pedro Trail, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Trying to decide whether to plow ahead through the jungle of tall grass, or play it safe and walk. We tried both strategies at times. You can see the border fence less than a mile away. San Pedro Trail, US-Mexoco Border, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Within 100 ft (30 m) of the border, we popped out of the vegetation onto an open road that parallels the border fence. The land immediately adjacent to the fence has been totally cleared of vegetation, presumably to watch for illegal activity. We crossed over the road, and posed for a victory photo next to the fence. After nearly four months of cycling, we made it!

Ta-da! Reaching the border fence marked the symbolic end of our cycling adventure from Canada to Mexico on the Western Wildlands Bikepacking Route. San Pedro Trail, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

The Road Home

We had reached the symbolic end of our Canada-to-Mexico bikepacking trip. But, of course, we still had to get home. The first requirement was to cycle back to Sierra Vista.

After bushwhacking and pedaling our way back to the Palominas Trailhead, we stopped for a break at some shaded picnic tables near the trailhead parking lot. As we sipped warm water and nibbled on gorp, we took a moment to reflect on the amazing journey we had just experienced.

On a lengthy bike packing tour, so many things can go wrong that might prematurely end the trip. We felt incredibly fortunate that we were able to make it all the way from one border to the other. We had our share of struggles, but the memory of those was already beginning to fade. The moments that came to mind most readily were the ones where we overcame obstacles, and had the chance to see remote corners of America that few other people have the opportunity to experience. More than anything else, we felt lucky.

Refreshed from our rest, we hit the road on our bicycles for the last leg of the trip. Our route back to Sierra Vista took us on paved roads that climbed into the foothills of the Huachucua Mountains. With a nice, wide shoulder to ride on, the miles passed quickly.

Heading back to Sierra Vista, our route took us into the foothills of the Huachuca Mountains (ahead). Palominas, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the way there still was plenty to see. We spotted an unusual church high up on the mountainside. And a strange, white object hanging in the sky turned out to be a border patrol, radar balloon.

Over the next few days we bought duffle bags for our gear, arranged for our bikes to be shipped to our house, and our bodies to be driven to the Tucson airport, where we caught a flight home.

A couple of frozen yogurt bowls, smothered in sweet toppings, helped us celebrate our victory. Pretty soon we’ll have to cut back on the calories. But one last splurge couldn’t hurt. Sierra Vista, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

We wouldn’t want to end this story without thanking the great staff at Sun & Spokes bike shop in Sierra Vista for safely packing and shipping our bikes back home to us. They really did a great job. Thanks, guys!

It’s always nerve-racking to leave your bike in someone else’s hands for packing and shipping. These guys were very helpful and did a great job. Thanks to Chris and Alex at Sun & Spokes bike shop in Sierra Vista for getting our bikes back to us safely. Sierra Vista, Arizona, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.