TransMexico Norte Part 1: Cycling from Mazatlan to Durango, Mexico

2 - 20 May 2023

2-3 May - Ferry from La Paz to Mazatlán (13.8 mi, 22.2 km)

3-5 May - Layover in Mazatlán

6 May - Mazatlán to Concordia (35.7 mi, 57.5 km)

7 May - Rest day in Concordia

8 May - Concordia to La Capilla de Taxte (26.5 mi, 42.6 km)

9 May - La Capilla de Taxte to El Palmito (21.7 mi, 34.9 km)

10 May - Rest day in El Palmito

11 May - El Palmito to Wild Camp along Hwy 40 (18.7 mi, 30.1 km)

12 May - Wild Camp along Hwy 40 to La Ciudad (16.3 mi, 26.2 km)

13 May - La Ciudad to El Salto (35.5 mi, 57.1 km)

14 May - El Salto to Parque El Tecuan (28.6 mi, 46.0 km)

15 May - Parque El Tecuan to Durango (34.5 mi, 55.4 km)

16-20 May - Layover in Durango

Farewell to Baja

We had spent the past 3.5 months cycling back and forth across and along the length of Baja California. The remote and rugged Baja Divide Bikepacking Route served up some of the most challenging cycling we had ever attempted. It pushed us to the limits of our abilities, while immersing us in the culture of Baja’s tough, yet deeply generous, desert ranching communities. It was bittersweet to say good-bye.

But the road ahead beckoned us, and it was time to shove off across the Sea of Cortez where we would resume our cycling journey in mainland Mexico. During our layover in La Paz we had purchased tickets on the big ferry that runs three times a week to Mazatlán, run by Baja Ferries. In the early afternoon on our final day in Baja, we re-packed our panniers so that we could leave our bikes below deck on the ferry. Everything we needed for a comfortable, overnight passage was stowed in our backpacks, which we would carry onboard. Around 1pm, we cycled northward out of the city.

The ferry to Mazatlán doesn’t actually leave from La Paz at all. The port lies nearly 12 miles (19 km) north of the city in a place called Pichilingue, which seems to exist solely as an industrial-sized terminal for big ships. (The official population of Pichilingue is 5 people.) To get there, we left the city on a well-maintained bike path for several miles, then followed roads that hugged the coast all the way to the port. We had been off our bikes for a while, so the 8-10 medium-sized hills along the way made us work a bit harder than we should have. But overall it was a pleasant and fairly uneventful ride.

Heading out of La Paz on the well-maintained bike path. La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Baja Ferries treats cyclists like pedestrians, not vehicles. So when we cycled up to the entrance of the ferry terminal, an official directed us to the pedestrian boarding area. That surprised us at first, because on most ferries we’ve taken - all around the world - it’s been more common for bikes to queue up and board with the motorized vehicles. But we had to admit it was nice to be able to wait inside the terminal, rather than outside with the cars and trucks.

The ferry wouldn’t depart until 7pm, but we had heard that it was good to arrive very early to avoid long lines. If you’ve pre-paid as we did, the process for boarding the ferry involves bringing your receipt to a ticket window to get your ticket and boarding pass, and passing through a luggage inspection area. The ferry is quite popular, so the lines can apparently get quite long.

But when we arrived at around 2:30pm, there were hardly any other passengers present. We got our tickets without any wait at all. A helpful gate agent then recommended that we park our bikes next to the entrance for the baggage inspection area (which would not open until 5pm). At that point, we settled into a couple of the not-so-comfortable chairs for the two hour wait.

Our bikes waiting to board the ferry from La Paz to Mazatlán. Pichilingue Ferry Terminal, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The wait ended up being a bit shorter than expected, since they started the boarding process closer to 4:30. We were thrilled when the staff let us through the gates first - before all of the other pedestrians. That was really nice, because we didn’t have to maneuver our bikes through a crowd of people with lots of luggage and quite a few young children. The baggage inspection process was extremely cursory. All they did was ask us to open our handlebar bags for a quick look by an official. Then we passed through a metal detector with our bikes, setting off all kinds of alarms, which didn’t seem to phase anyone. And before we knew it we were wheeling our bikes up and into the belly of the ferry.

Another official showed us to a spot along the wall inside the ferry where we could leave our bikes. It was then that we learned they expected us to tie our own bikes to the wall. We hadn’t planned for that. But luckily we had a bunch of extra guy-line rope, which we used to lash the bikes together and tie them to some metal eyelets on the boat. It wasn’t elegant, but it worked.

From there we trudged up several flights of stairs with our backpacks, handlebar bags, bike helmets, and a bag of snacks. We had pre-booked a cabin in hopes of arriving in Mazatlán reasonably well rested. Once we were on board, registration was easy, and a steward helped us find the right cabin quickly. The room was small, but it was actually a bit bigger than many other ferries we have been on. It was very clean and comfortable, with plenty of room to stow our luggage out of the way.

Then we went for a walkabout. The outdoor deck area of the huge boat was surprisingly small. Passengers only had access to one deck at the stern of the boat. Plus, there was no way to get close to the outermost railing for a good view. The perimeter of the deck was fully blocked by lifeboats and other equipment, or cordoned off with yellow “hazard” tape. The lack of railing access was so complete that we came to the conclusion the ferry company did it on purpose, so they wouldn’t have to worry about losing any passengers overboard. Unfortunately, it made taking photos or enjoying the scenery a lot more difficult.

Dinner, which was included in the price of the ticket, was served in the boat’s restaurant before shoving off from the dock. A line of people had formed, waiting for the restaurant to open at 5pm. But by 5:30 the line was a lot shorter, so we headed in to see what they had on offer. The food was served cafeteria style with three different entrees to choose from, plus sides of frijoles, mashed potato’s, tortillas and a small, fresh salad. Jello for dessert. The food was good enough, and we enjoyed a filling meal.

After dinner we went back outside on the deck to watch the boat’s departure from the harbor. We were intrigued to see that there were a handful of tugboats standing by to help guide the big ferry out of the narrow mouth of the harbor. Their lights glowed brightly in the fading daylight, as they shepherded our boat out into the more open waters of the Bay of La Paz. Too bad the city of La Paz was so far away. Its twinkling lights were just a thin line on the horizon as the ferry turned northward into the Sea of Cortez.

A tugboat guides the La Paz to Mazatlán ferry out into deeper waters. Bay of La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As the ferry steamed into the darkness, we went below to kill some time before calling it a night. The boat has multiple “salons” packed with airplane-style seats and playing the same movie (in this case, Black Panther), 24 hours a day in constant rotation. These are the areas where passengers “sleep” if they haven’t booked a cabin. With the bright lights and loud volume of the movies, we would have been hard pressed to get any real rest there.

We spent some time in one of the salons watching the movie, but it was dubbed in Spanish so we couldn’t follow the story very well (we had not seen the film previously, and it seemed to have a very complicated plot). Giving up on that, we went back to the restaurant, where a couple of singers were performing a live show, drenched in purple stage lights. That was fun for a little while. Then we headed back to our cabin.

The boat was very quiet, and the beds were reasonably comfy (if a bit small and cramped). Despite warnings from the staff that the room might get too hot, it stayed comfortably cool. And the boat rocked us gently all night.

Exploring “The Pearl of the Pacific”

Once the boat was safely in the dock, one of the stewards came to find us so we could be led down to our bikes before the other foot passengers were allowed to go. Most of the cars and trucks had already disembarked. And by the time we had untied our bikes and were rolling down the gangplank, the other pedestrians were right behind us. We had arrived in Mazatlán, Pearl of the Pacific.

The giant Baja Ferries boat rested at dock, as we made our way into Mazatlán. Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The ride into the old town was short, but very scenic. At least half of the time we were cycling right along the waterfront.

The Cerro de la Nevería (“Ice Box Hill”) stands out prominently along the shoreline separating modern Mazatlán from the historic Centro. In the 1800s, limestone caves that honeycomb the hill were used to store ice shipped in from San Francisco, hence its name. Having access to ice drove a boom in Mazatlán’s seafood industry. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We spent two full days in Mazatlán, exploring the old colonial center and strolling along the city’s endless malecón (seaside promenade). Here are some of the sights we encountered:

Built in the late 1800s, Mazatlán’s Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception is relatively new by Mexican cathedral standards, and its exterior is a bit more gothic than the ornately baroque facades on many earlier mission churches. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Bursts of color appear everywhere in the colonial Centro. Colorful streamers or other decorations often are hung from trees or overhead wires, giving you the feeling that you’ve stumbled upon an outdoor party.

Glittering piñatas and streamers create a festive atmosphere at a restaurant beside the Plaza Machado. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Even when there weren’t any additional decorations, the buildings themselves were painted in bold colors that brightened up the narrow colonial streets.

Just a couple of blocks from where we were staying, we were surprised to stumble upon a little corner of England. The first thing that caught our eye in Liverpool Alley was the life-sized statue of the Beatles ripped right from the cover of the Abby Road album. A red, English phone booth, a MINI Cooper car, and a replica of the Yellow Submarine rounded out the Liverpool theme.

Mazatlán has one of the longest seaside promenades in the world - running for thirteen continuous miles (21 km). Known as the Malecón, this bustling waterfront offers some of the most enjoyable views of the city and bay, as well as tons of public art, palapa-shaded restaurants, an ocean-filled swimming pool, platforms for cliff divers, and some of the best surfing in western Mexico. Each morning we went for a long stroll along the Malecón, soaking up the tropical ocean vibes.

PedalingGal ascends the stairs to one of the cliff-diving platforms. The divers prefer to work in the afternoons, when they can draw big crowds. So we had the platforms to ourselves in the morning. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The Carpa Olivera was a pretty cool sight. It’s a concrete swimming pool built right into the ocean. Waves crash over the outer wall, keeping the pool full. When we passed, the pool appeared to be closed (there was yellow tape across the entrance). But some local ladies had gone down for a swim, anyway. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Beware the Cueva del Diablo (the Cave of the Devil). A red gate protects the entrance to a tunnel in the side of Cerro de la Nevería (Icebox Hill). Legends say the cave leads to the underworld. Within the hill is a labyrinth of tunnels that over the years served as a hiding place for pirates (1500’s), a storehouse for ice in the seafood trade (1800’s), and most recently as a repository for dynamite used to construct the road that hugs the coast (mid-1900s). But legends about the devil have persisted for centuries, including stories of people disappearing in the caves - never to return - and claims from road workers that they heard or saw strange things within the tunnels. Who knows?

A red gate keeps hapless tourists from entering the underworld via the Cueva del Diablo (Cave of the Devil). Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

For more than 200 years, Mazatlán was a notorious pirate hideout. The outlaws would launch surprise attacks on Spanish galleons that carried Mexican gold and silver across the Pacific. These days the pirates are much more conspicuous, especially around restaurants and souvenir shops. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

There are really two Mazaláns: the colonial Centro (seen in the photos of colorful buildings shown above), and the separate, more modern city that lies several miles further up the coast.

View from the Malecón across the bay, towards the modern skyline of Mazatlán’s Zona Dorada (Golden Zone). Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A surfer rides a wave perilously close to rocks near the Mazatlán Malecón. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A fanciful shopping area at Punto Valentino, part of the modern Mazatlán. Sinaloa, Mexico Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling Into the Foothills of the Sierra Madre

On 6 May 2023 we were finally ready to pull ourselves away from the charms of Mazatlán, and begin the long ascent from the coast. We would cycle into Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental - the majestic spine of mountains that runs along the western side of the country. Over the next week or so we would climb from sea level to over 9,000 ft of elevation (2,750 m) - nearly as high as Quito, the capital of Ecuador in the Andes. It is a huge undertaking on a bicycle - similar in scope and difficulty to the momentous climb from the Sahara Desert up onto the Ethiopian Plateau which we cycled in 2019. (Actually, the ride in Ethiopia was both shorter, and had a bit less in elevation gain).

Conditions for our ride were not exactly ideal. Due to our layovers in La Paz and Mazatlán, we had not done any serious cycling for two weeks. That meant we had lost some of our physical conditioning, which we would have to regain along the way. In addition, May is one of the hottest months in this part of Mexico, with cloudless, humid days. The afternoon cycling would be oppressive in the heat, especially at lower elevations. And finally, PedalingGal was still on the mend from a stomach bug she had contracted the day before, and so was not feeling 100%. We would soon see if we were up to the challenge.

The day started off well enough. We were up early, and on the road by 7am. It was a Saturday morning, so traffic in the city was light, and our exit from the urban center went smoothly. In just 10 minutes we reached a small, fairly informal dock. From there, we caught a pedestrian ferry across the broad canal that lies between Mazatlán’s old town and Isla de la Piedra on the the Mexican mainland. It took just a few minutes to secure our tickets, which cost just 25 pesos each (less than US$1.50). And moments later we were gingerly positioning our fully-loaded bikes in the bow of a waiting lancha boat.

Prepping the bikes for loading onto the small ferry, which would whisk us over to Isla de la Piedra. The ferries run on demand, with waits usually being less than 20 minutes. We were able to board a departing ferry right away. Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Scooting across the canal from Mazatlán to Isla de la Piedra. The ferry ride was quick, lasting no more than five minutes. (Our bikes can be seen in the bow of the boat, along with a local cyclist’s steed.) Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Commercial fishing appeared to be a big part of the economy on the Isla de la Piedra side of the canal. There were lots of fishing boats of all sizes, as well as stacks of fishing gear piled around the docks.

Piles of fishing nets on the dock. Isla de la Piedra, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A line-up of some of the bigger fishing boats. Isla de la Piedra, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Although our route paralleled the coast for more than an hour, we weren’t close enough to see the water. We were separated from the ocean by a huge coconut plantation that is more than seven miles long, and half a mile wide. It was quite an experience to cycle past mile after mile of tall, graceful coconut palms in plantation-style rows. They say that more than 10,000 coconuts are exported from here every week to cities throughout Mexico. That’s a lot of coconuts.

Across the road from the coconut plantations was a mix of farms, mangrove swamps, and scrubby woodlands. And from the woodlands came a periodic, startlingly loud squawk that sounded a lot like a rooster with a sore throat. It was strangely enigmatic, and we wondered what could make such an ear-splitting, exotic-sounding call?

It didn’t take too long for us to find out, because the creature making the noise was also inclined to perch high in the bushes where it was relatively easy to see. The call was coming from male rufous-bellied chachalacas - a large, game bird reminiscent of a pheasant. But it was tough to get a reasonable photo of one, because they always seemed to be backlit by the morning sun. Still, it was fun to spot them in the trees, and pedal along to the cadence of their raucous calls.

We stopped at this rural restaurant shortly before reaching the town of Villa Unión for a cold drink in their air-conditioned dining room. At 10am the day was already heating up fast. The cloudless sky also called for applying a bit of sunscreen in the shade of the restaurant’s porch. Near Villa Unión, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As the clock turned toward 11am the temperature was already creeping into the 90s F (30s C), and we started getting into the foothills of the Sierra Madre mountains. They weren’t too steep, and should have been relatively easy to climb. But the heat and humidity took their toll. PedalingGal really struggled, battling nausea from her not-quite-healthy stomach. Some precious Gatorade powder that we had been carrying since early March helped save the day. (Gatorade bottles are ubiquitous in stores. But the powder, which is lighter and can easily be carried for long distances, is very rare in Mexico.) After PedalingGal drank some of that, she felt a little better. The remainder of the ride was not particularly fast, but we were able to keep moving.

By the time we reached Concordia’s leafy central plaza, the mercury had risen to 102 F (39 C). Needless to say, we didn’t linger. We made a bee line for a small hotel close to the Centro. It was pretty basic accommodation, but it did have air conditioning and hot water - both lifesavers for two tired cyclists. We cleaned up and rested in the room throughout the hottest part of the day. The opportunity to gain some elevation in the Sierra Madre mountains over the next couple of days - which would take some of the edge off of this heat - was starting to look very appealing.

Around 5:30pm we finally ventured out of our nice, cool room for a walk around town. Even with the sun sinking toward the horizon, it was still 98 F (36.5 C). In typical Latin American style, the central plaza is dominated by the town’s beautiful, old church. The mission in Concordia was established in 1565, way before any of the missions we had visited in Baja. But the current church was built much later, in the 1700s. It had an ornately carved, baroque facade that was offset by an oversized bell tower, with a really big bell inside.

San Sebastián Church glowing in the evening light. Concordia, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Each town and state in Mexico has its own coat of arms. In Sinaloa, they seemed particularly enamored of displaying these designs. The heraldic shields of all the towns in the municipality of Concordia were painted along a length of road leading away from the plaza. Concordia, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A Big Climb on the Road Less Traveled

After taking a day off in Concordia to allow PedalingGal to fully recuperate, we were ready to tackle the ascent into the heart of the Sierra Madre Occidental. And it would be a really big climb. For comparison, the ride we had just completed from Mazatlan to Concordia was roughly 36 miles (58 km), and gained about 1,200 ft (365 m). The next day’s ride would be 10 miles shorter, but would ascend a lung-busting 4,200 ft (1,280 m). We needed to be feeling our best.

The next morning we arose at 5am, hoping to get out on the road as early as possible to beat the heat. Even so, we started the ride in our shorts and short sleeves before 6:30am. And by 8am it was downright hot.

We cycled out of town on Highway 40, also known as the Interoceanic Highway. Built in the 1940’s, it was an engineering masterpiece of its time. It was the first fully paved road to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Mexico, giving a shot of adrenaline to the economies of the towns along its length. This was especially true on the section that ran from Mazatlán to Durango (which we were cycling) where small, isolated mountain towns could now ship to and receive goods from the big cities.

But the road was only one lane in each direction (sometimes barely that), and had lots of dangerous curves. By the 1960s, it wasn’t really suitable for modern shipping that relied on big, diesel trucks. So plans were put in place for a new superhighway. Yet because of the extreme challenges posed by the Sierra Madre mountains, the final length of the new highway from Mazatlán to Durango wasn’t completed until 2013. The limited-access toll road has 63 tunnels and 115 bridges, reducing the trip that took more than 12 hours on the old highway to less than three hours. For obvious reasons, Mexicans vastly prefer to take the new superhighway, rather than the narrow, winding Hwy 40.

That makes Highway 40 perfect for cycling. After departing from Concordia, the traffic volume quickly dropped off until we were riding on a beautifully scenic road with very few vehicles. The views of the mountains were quite dramatic as we gained altitude, even though a lot of the trees were still leafless because we were in the dry season.

Looking towards the Sierra Madre mountains from Highway 40, just north of Concordia. Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

At first the ride was not too tough. The hills were moderate, and we moved along quickly. After only two hours, we had covered half the distance we had planned to ride for the day. It was the second half of the ride where the mountains really kicked in. The gradients became steeper, and flat sections became scarce.

Just past the halfway point we stopped at a little tienda near a road junction. By then the sun was beating down, and we were ready for a break. We sipped cold drinks in the shade of a palapa, in the company of the store’s five dogs and two cats. It was heaven.

As we ground our way up the slopes, we left the coastal dry forests behind and entered a realm of pine and oak trees. There weren’t many fences, so it was pretty common to see cows wandering along the side of the road - and even standing in the traffic lanes. Much of the area was open range where the cows wear bells so that the owners can find them. Just another reason that Hwy 40 is considered dangerous, and drivers prefer to take the faster toll road.

Free range cows would typically stare at us with mild curiosity as we rode by. Hwy 40 North of Copala, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Rising higher into the steep-sided mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental. We could see the high-speed toll road crossing over bridges and through tunnels on distant slopes. Hwy 40 North of Copala, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling through the pines. Hwy 40, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we gained elevation, we struggled with the heat. We began stopping at half-mile intervals to rest in the shade, which thankfully was provided by the big pine trees. With all of the breaks, it took us five hours to cover the second half of the ride. But we finally arrived in the tiny hamlet of Capilla del Taxte (pop. 52), brutally tired.

We were delighted to find that both the hotel and the little tienda in town were both in business. A sweet, elderly lady named Irma checked us into the hotel, giving us a room on the first floor with five (yes, five) beds for just under US$20 for the night. But at that price, you can expect some drawbacks. One of the lights had a short in its wiring, sending sparks flying when we tried to use it (not a great thing in an old, wooden hotel). The toilet didn’t have a seat (a fairly common situation in Africa, but our first encounter with that in Mexico). And there was no air conditioning or fan. But none of that mattered. It was a relief to get out of the scorching sun, and we were able to clean off the salt that had crusted on our skin. Drinks from the tienda across the road were cold. So it was all good.

The little tienda across the road from our hotel. The selection of items in these stores is limited, but you can count on getting cold drinks and snacks, and often other staples like tuna and crackers. Capilla del Taxte, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

After we had settled in and were resting in the shade on the front porch, a couple of cars drove up to the hotel. Other guests! That’s how we met Octavio, Rosaria, and César who were all geologists employed by mines in the area. Octavio was the senior manager. He spoke English as well as a bit of Portuguese that he had learned while working for a Brazilian company in the past. He also had worked for a while in the USA at a mine in Arizona. But he had to drive Rosaria to Mazatlán that evening to catch a flight home, so we didn’t have much time to visit with either of them.

However, when we asked them whether there was a restaurant in town, Octavio invited us to eat with César. Their company had arranged for a woman in town to cook meals for the mine workers at her home. We gratefully accepted the offer, and César called ahead to let her know that there would be two more mouths to feed.

Dining with César was a special treat. It was just the three of us, and we had all the carne asada tacos we could eat. César was a wonderful host, and we enjoyed chatting with him during the meal. We learned that the primary ore being mined in the area was silver, with some gold as well. He would spend 20 days working in the field (staying in a hotel), then get 10 days off when he could return home. His job took him all over Mexico, working on contract for different mines and companies.

When we were finished eating, the hostess said she would be making sandwiches for dinner. César offered to bring us each a sandwich later in the evening, around 7pm. It was very generous, and saved us from having tuna and crackers for dinner. We were incredibly grateful. The two, delicious meals set us up perfectly for tackling the next big mountain climb the following morning.

Crossing Into the Tropics

It was a hot and stuffy night. The air outside cooled down, but that didn’t help us much. Our hotel room had no screens on the windows. So as dusk settled in, and a handful of mosquitos found their way into our bedroom, we decided to close the windows for the night. Without a fan or air conditioning, we sweltered in our enclosed room. Plus, the few mosquitos that had slipped in before the closure buzzed in our ears and bit our arms, keeping us awake.

Unable to sleep, we were up at 4:30am and out on the road by 5:45am. On the bright side, we would get in a couple of extra hours of riding before the day heated up. The elevation gains from our early start also meant the afternoon temperatures wouldn’t be quite as miserable. So, although we were groggy, we were pleased with the way the day started.

We were out on the road in time to catch the sunrise over the mountains, and a modest house with a million dollar view. La Capilla del Taxte, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It was another day of climbing. The first 12 miles (19 km) were the toughest, with nearly 3,000 ft (915 m) of elevation gain. As we plugged along on the endless ascent, the road twisted and curled around a relentless series of hairpin turns. The engineers that built this section of road had their work cut out for them, negotiating a path through some of the steepest mountains in the Sierra Madre. One look at a map of our route that day and it is obvious that this terrain was rugged - the road squiggles so much that it looks like a ramen noodle splattered on a table.

Map of our route from Capilla del Taxte to El Palmito, Sinaloa, Mexico. The terrain was so rugged and steep that our route squiggled through the mountains along a relentless series of hairpin turns. (Our route is shown as a red line. The blue dot marks the end of the first 12 miles, and the end of the steepest part of the ascent.) Map by Ride with GPS.

Traffic was very light. As we wound our way up the side of the mountain, we would be passed by a vehicle every couple hours. Interestingly enough, the vehicles were often buses serving the people who live in some of the remote mountain communities. Our route passed back and forth over the newer toll road (the road with all the traffic) which cut a straighter line through the hills. As we snaked our way through the mountains by hugging the steep slopes, the superhighway bored its way through tunnels and over bridges.

This ramshackle miners’ cabin sat on a hill overlooking one of the places where our route crossed the new superhighway. Looking closely, we realized the cabin was haunted, and we were being watched. Highway intersection north of Sant Lucia, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The winding nature of the route meant that we often had views looking back on the road we had just traveled, hundreds of feet below us. This picture shows one of the larger mountain towns. Potrerillos, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Frequent stops to rest meant that we had plenty of opportunities for encounters with roadside wildlife - including the jaw-droppingly magnificent black-throated magpie-jay. It’s hard to describe just how astonishing these birds are. They grow up to 27+ inches (70 cm) in length, with more than half of that comprised of their long, flowing tails. On top, they sport a jauntily curved crest that looks like a feather stuck in their cap. In places along the route they were downright common, flying back and forth across the road squawking loudly the way jays do. But we were still lucky to see them. Black-throated magpie-jays only occur in the higher elevations of Mexico’s western Sierra Madre mountains.

Some of the other roadside wildlife was not so welcome. Dozens of red bites on our legs were evidence that we must have waded through some grass infested with biting bugs, similar to chiggers.

But the big event for the day was that we crossed out of the temperate zone and into the tropics. That is, we crossed the Tropic of Cancer - the imaginary line on the earth where the sun is directly overhead at noon during the summer solstice. The land between the Tropic of Cancer (in the northern hemisphere) and the Tropic of Capricorn (in the southern hemisphere), is officially known as the tropical region. No wonder it was so hot.

We’ve made it into the tropics! Today we cycled across the Tropic of Cancer. Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

About 4.5 hours into the ride we finally reached the top of the biggest ascent. From there, we cycled through a roller coaster of high-altitude ridges, with fast and fun downhills to break up the climbs. That was fantastic, because the breaks from climbing, and the cooler, high altitude temperatures made the mid-day cycling much more pleasant.

Unfortunately, as we cycled higher into the mountains there was a heavy layer of smoke in the air. May seemed to be the “burning season” in the sierras, and lots of people were burning brush to clear land or to establish fire breaks on their property. We also saw at least one, very big forest fire on a ridge not too far away. There were times when the smoke from roadside brush fires was so thick that it burned our eyes and we could see ash falling in the road. Needless to say, the “spectacular views” we should have witnessed in the afternoon were hidden in the haze. We were glad that when we finally reached the town of El Palmito (pop. 576), the air had cleared a bit and we could breathe a little easier.

A member of the welcoming committee in El Palmito, a small, mountain village where we spent the night. El Palmito, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The modest hotel in El Palmito was a big upgrade from the one where we had stayed the night before, even though the price was the same. Almost everything about the room was in a little bit better shape. But the best features were that there were screens on all the windows (so we could have a cool breeze at night), and the room had a refrigerator where we could keep a stash of cold drinks (a very rare thing in Mexico, and a total surprise in a budget hotel). Given how poorly we had slept the night before, it didn’t take much to convince us to take another rest day in El Palmito. We used the time to catch up on sleep, rest our tired legs, and acclimate to the change in altitude since we were now nearly 7,000 ft above Mazatlán. For anyone familiar with the United States, this is higher than Mount Mitchell (6,684 ft) the tallest mountain in the Eastern United States.

To pass the time we went for a walk along the quiet highway. We continued to be smitten by the beautiful and exotic-looking birds that were relatively easy to spot along the side of the road.

As an added treat, the hotel manager gave us five oranges from his orchard, which was growing just across the road. They were sweet and delicious.

Oranges from the hotel manager’s orchard - a wonderful afternoon snack. El Palmito, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Unfortunately, on our second night around bedtime, the house right behind the hotel started blasting music loud enough to fill a 100,000 seat stadium. We appreciate lively Mexican music, but when it lasted until midnight, it definitely impacted the quality of our sleep. Loud music is much more tolerated in Latin America. We just got unlucky this time.

The Spine of the Devil

The next morning we were delighted to wake up to a nice, cool morning - the first we’d had in quite a while. The altitude change was finally starting to work in our favor.

The section of Hwy 40 between El Palmito and La Ciudad is affectionately known as “Espinazo del Diablo” (the Spine of the Devil). We hardly thought it was possible, but this part of the highway traversed even more rugged terrain than what we had cycled over the past few days. For long stretches, the highway seemed to be just barely etched into the side of steep cliffs that rose spectacularly overhead on one side, and dropped off precipitously on the other. In a few places, the road followed ridgelines where the terrain fell off sharply into dark valleys on both sides. The scenery was very dramatic, and we stopped often to soak up the majesty of the mountains. Smoke from fires still hung in the air. But it had settled into the cool valleys, leaving the air at higher elevations more clear. Visually, the effect was quite stunning.

Morning in the Sierra Madre mountains. Smoke from fires shrouds the valleys, while the taller peaks rise into the sunshine. Espinazo del Diablo, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

On this stretch of the road we passed a number of little shops that were closed. It wasn’t clear if they were not in business anymore, or if our timing was just off. Often we would see stores or restaurants with signs saying they were open 24 hours. But this was almost never true, since they were mostly closed. Maybe the signs and restaurants were left over from the days before the superhighway was built, and drained most of the traffic off the road we were on. Puerto El Yesquero, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Scenic bluffs rose high above our route. Espinazo del Diablo, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One particularly large forest fire was pumping out smoke on a far ridge. Fortunately, the wind was in our favor, and it blew the smoke away from us. Espinazo del Diablo, Sinaloa, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Ever since leaving the town of Concordia in the lower foothills, we would occasionally catch glimpses of the high-speed toll road that had replaced Hwy 40 (the road we were riding). Usually we would see a distant bridge over a ravine, or the road emerging from a tunnel. On this day we spotted a suspension bridge which we later learned is quite famous. The Baluarte Bridge, which opened for traffic in 2013, rises 1,320 ft above the river below. Until 2016 it was the highest bridge of its type in the world, and it remains the highest in the Americas. Completing the bridge in such remote and forbidding terrain was one of the crowning achievements in engineering represented by that remarkable road.

We spotted the Baluarte Bridge on the Mazatlán-Durango superhighway through the smoky haze. In this photo, the suspension bridge (the highest in the Americas), can be seen just below center. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

In several places the road teetered along the edge of a ridge between cliffs. The school seen in this photo was perched in one of those saddles, where the terrain fell off dramatically on both sides of the ridge. The schools in this remote area usually were very small, with just a few classrooms. But they always had a very large veranda on the front for shelter from the sun (lower left of the photo). Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Looking back at the road we had traveled. You can just see the line of the highway, hugging the side of a gigantic cliff. If you look closely, you can see a full-sized, inter-city bus. Its tiny size gives some perspective on just how far away the road is, and how massive the mountain is. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As rugged and forbidding as the mountains were, there were still people who lived and worked there. We passed this lumber mill, with the sound of buzzsaws and the smell of sawdust rising through the air. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Making progress. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Every so often we would see a small village down deep in one of the valleys or perched on a far ridge, and wonder, how do the inhabitants get down there? Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

In the end, with a short night’s sleep and a late start, we decided to call it a day after cycling just 17.5 miles (28 km). We found a beautiful, peaceful, wild campsite on a pine-covered ridge that was well hidden from the road. After pitching the tent on a soft bed of pine needles, we rested in our camp chairs for a couple of hours, chatting and listening to the sound of the wind in the pines. It was very relaxing and tranquil, compared to the last couple of difficult nights in hotels. A Mexican whip-poor-will serenaded us for a short time after dark. We both slept great.

Our wild camp among the pines. Just two days ago it had been almost too hot to cycle. Now, at nearly 8,000 ft (2,440 m), PedalingGal needed her down coat to stay warm in the evening. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As the sun set we took a short walk to an overlook. The evening light cast theatrical shadows on the rugged cliffs. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The next day we covered the final miles on the Espinazo del Diablo to reach the mountain town of La Ciudad. There were plenty of steep hills. But now that we were high in the sierras, there were almost as many downhills as ascents, while we careened over a series of mountain ridges. That made the terrain much less strenuous.

You can just barely read it, but this sign confirms that we were on the Espinazo del Diablo. State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We caught sight of several high, isolated peaks that reminded us of the Sky Islands in Arizona and Sonora, or even the tepuis in Venezuela. We wondered if there were any rare plants or animals on top. Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Given all the smoke and fires in the area, this sign seemed appropriate. It means, “Prevent Forest Fires.” Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

This road sign uses a gentle touch to encourage safe driving. It means, “Drive With Care, You’re Family Is Waiting For You.” Espinazo del Diablo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We arrived in the town of La Ciudad without much of a plan on where we would stay. As a “gateway community” to the Mexiquillo Natural Park, La Ciudad has an abundance of cabins for rent. But they are all individually operated, and often aimed at families with lots of beds and way too much space for us. Online information about the various options was very sparse and confusing, making it hard to hone in on the best lodging option. We had to come up with a solution on the fly.

The first thing we tried was asking the folks in the village’s main supermarket if there was a hotel in town. With a puzzled look, they pointed to a building across the street and declared that it was a hotel. But when we went over to the door on the building it was locked. Multiple efforts to rouse someone by ringing the doorbell didn’t work. There was no sign posted with a phone number to call for help (a fairly common practice in small towns). So that hotel was a bust.

We then thought we might try checking out some of the cabins. Cycling around near the entrance to the park, we finally pulled in to the driveway of a cluster of buildings that had a sign out front promoting cabins for rent. But it was not clear where to go to find a proprietor. As we stood in the driveway wondering what to do, a pickup truck pulled in, and some folks got out.

A woman who seemed to be in charge came over and asked if we were looking to rent a cabin. Yes! However, when we mentioned that we were looking for something small, for two people, it became clear that she did not have anything that fit the criteria. But she was very kind and wanted to be helpful. so she started texting and calling some of her friends to see who might have something we could rent. Unfortunately, the only thing she turned up was a cabin outside of town, several miles away. Not really what we had hoped for.

We then confirmed with her that there was another hotel in town, a little over a half mile away. We decided to go there.

That’s how we ended up at the cheerily painted Hostal Mexiquillo. But our struggles were not over just yet. The patient and helpful receptionist showed us most of the rooms on offer, but they were all either really tiny (no room for the bikes), or on the second floor, which could only be reached by climbing a set of stairs too narrow for the bikes. Just as we were wondering whether we would have to move on, the receptionist asked if we would want to stay in a cabin. It turned out that in back of the hotel, they also had a cabin for rent, with seven beds. But it was getting late in the day, and maybe she figured that the cabin wouldn’t rent that night anyway, so she offered it to us at a discount. We gladly accepted.

You can’t miss the Hostal Mexiquillo. It’s one of the most brightly colored buildings we’ve seen - and that’s saying something in Mexico. La Ciudad, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The cabin had a lot of space and features we didn’t really need. But one thing it did have was a nice, warm shower. That was the best.

Like most of the cabins in the area, this one didn’t have heat. Instead, it had a big fireplace in the main room. But we weren’t that interested in tinkering with a fire, and decided to just let the cabin get cold. And at 8,500 ft in altitude (2,600 m), it did get very cold. We snuggled down into the piles of blankets that they provided, and went to sleep. We had survived cycling the Spine of the Devil.

Otherworldly Rocks and an old Rail Trail

According to our weather app, the temperature got down to 45 F (7 C) during the night. But it felt a whole lot colder to us inside the cabin. With all of the recent hot weather, we had gone soft. Even temperatures well above freezing chilled us to the bone. We bundled up in most of our warm clothes just to have breakfast.

The day began with a magical ride among the amazing rock formations of the Mexiquillo Nature Park (Parque Natural Mexiquillo). Known as the stone garden, it is covered with softly rounded towers of volcanic rock that rival other, more famous locations like Arches Natural Park in Utah.

Cycling among the volcanic towers of the stone garden. Parque Natural Mexiquillo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But the ride through the stone garden was not very long, and in less than a half hour our route dropped down into a narrow ravine that had been carved through the bedrock to create a railroad bed. In fact, the railroad line was never completed. The project was scrapped in the mid-1900s when it was superseded by a different train route to the sea. But nearly 30 miles (48 km) of the route was leveled through the mountains along a series of embankments, rock cuts, and even tunnels that are now open to the public as a rail trail.

Cycling through the high mountain pine forests along the rail trail continued the sense of wonder that began in the stone garden. The air stayed fresh and cool as we cycled past rocky embankments and among some of the tallest trees we’d seen in Mexico. Often the route would break out of the forest onto a ridgeline, with spectacular views of the forested slopes of the Sierra Madre mountains. Like all rail trails, the gradients were long and gentle - much easier on our legs than the route taken by the Espinazo del Diablo. The tranquility was palpable. We didn’t encounter a single person along the entire 30 miles of trail.

Cycling among the tall pines near Mexiquillo Natural Park. Terraplén Tren Mexiquillo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The deep green of the pine-covered mountains was a refreshing change from the drier, browner, more open forests we had ridden through on our way up from the Pacific Coast. Terraplén Tren Mexiquillo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We enjoyed the ride so much that we decided we would stop to wild camp before reaching the town of El Salto. We had been having a string of bad luck with the town hotels, where there always seemed to be a reason we didn’t get a good night’s sleep. On the other hand, up on the mountain there were lots of promising looking campsites. We figured we would sleep a lot better in the quiet woods. A formal campground along the descent off of the mountain would be a good spot to pick up the extra water we would need to spend a night in the forest.

With that idea in mind, we slowed down our pace and took lots of breaks to photograph and enjoy the abundant wildlife and majestic scenery.

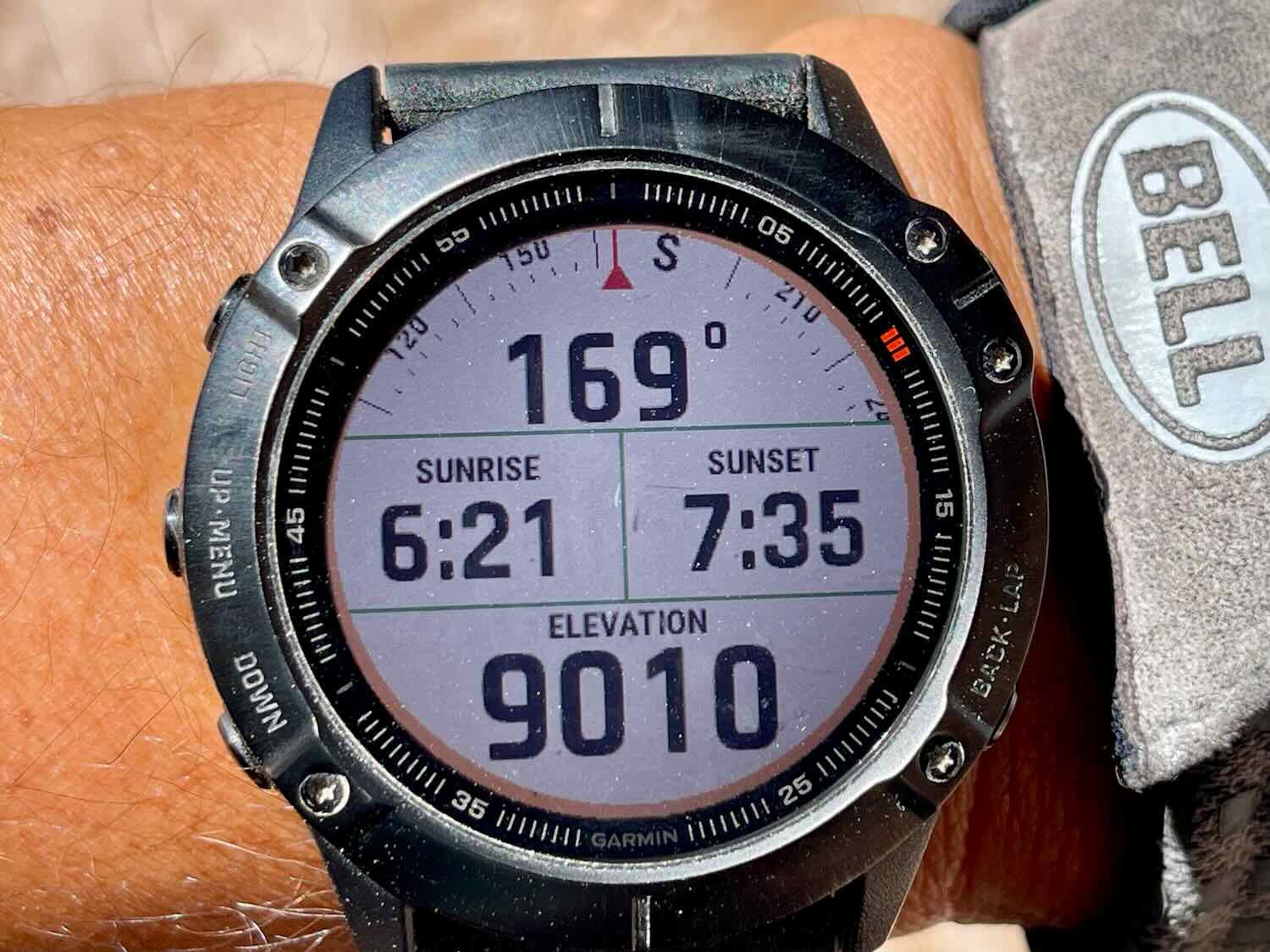

We cycled through two tunnels along the way. The second tunnel was long enough that for several minutes we were unable to see the ground in front of us. Fortunately, the surface of the trail within the tunnels was smooth and straight, so we were able to keep cycling without having to get out our headlights. But it was definitely a bit sketchy in the darkest part. The longer of the two tunnels cut through a mountain right near the highest point on our ride to Durango, where we reached an altitude of over 9,000 ft (2,745 m).

Emerging from the first of two abandoned train tunnels. Terraplén Tren Mexiquillo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The descent from the heights of the Terraplén Tren Mexiquillo, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Five hours into the ride we finally reached the La Pirámide campground, part way through the descent off of the mountain. It was a surprisingly fancy campground, with a cluster of inviting-looking cabins. We pulled up to the main office to inquire about water, and were immediately drawn in by the attractive, on-site restaurant. We enjoyed a very satisfying meal under the large, wooden canopy. It was luxurious. And as a bonus, we were able to fill our water bottles with delicious spring water.

From there we planned to cycle a few more miles down the trail and find a place for a wild camp. We had seen tons of very nice camping spots before reaching La Pirámide. But past the campground, what had been a quiet, forest trail suddenly became a populated gravel road. For the rest of the day the road was lined with barbed-wire fencing on both sides. As we rode past farms and ranches, we began to suspect that wild camping was not in the cards. Our plan was foiled.

Our quiet forest trail quickly turned into a rural farm road, lined with ranches and barbed wire fences. Approaching El Salto, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We had a bit of excitement when the road crossed a deep stream channel on a very rickety, old wooden bridge. Many of the boards were only loosely attached to the main structure. And it looked like the whole thing was being held together by bubble gum and a prayer. We didn’t quite realize how bad the condition of the bridge was until we were about halfway across. At that point the best thing seemed to be to simply hurry along and hope for the best. We quickly rumbled across the shaky boards, glad to have made it to the other side.

A particularly sketchy bridge along our route. Approaching El Salto, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Just before reaching the lumber town of El Mil Diez, we saw a dirt road heading up a hill. Still hoping to camp, we decided to check it out. We pushed our bikes up a steep and highly-eroded section of gravel for nearly a quarter of a mile. At the top of the ridge, a lovely, pine tree studded, grassy field appeared to be the perfect place to camp. But as we looked around, we realized that there were ranches very nearby. After wandering around the field for 45 minutes trying to find a spot that would be sufficiently discreet, we finally gave up. Reluctantly, we got back on our bikes and headed down the road towards the town of El Salto.

On the outskirts of El Salto we rode through a very active lumber town with sawmills everywhere. There were piles of logs and lumber covering acres of land. The sound of buzzing saws filled the air. El Mil Diez, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Given our recent experiences, we had low expectations for the hotel by the highway in El Salto. But we were pleasantly surprised. The room was clean and comfortable, the wifi was pretty good, the shower worked without surprises, and it was set back from the highway, so it was nice and quiet. We both slept really well.

A Camp Among the Pines

The hotel room in El Salto didn’t have heat, so it was quite cold in the morning. Still enjoying the comforts of our room, we stayed snuggled under our plush blankets until well past sunrise. It was a Sunday morning, so our late departure wasn’t really a problem. The traffic on the road was nice and light.

The friendly Chihuahua at our hotel came to wish us ‘buen viaje,’ but he got distracted by the scent of one of our water bottles. El Salto, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

This restaurant had a couple of kettles out front simmering over open, wood fires. They were cooking up a special Sunday stew. El Salto, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The day’s ride was uneventful. We were passed by quite a few lumber trucks. Sunday also seemed to be the time for folks to be out riding on their motorcycles. Several large packs of motorcycles (and dozens of smaller groups) whizzed past. Even though there was no shoulder on the highway, the traffic was light enough that we didn’t have to worry too much. Vehicles could easily pass us with plenty of room to spare.

In less than four hours (including a lunch stop) we arrived at Parque El Tecuán, a state natural area that was designated as an ecological reserve in 2018. Although there were a number of cabins for rent, the tent camping was pretty informal. Once we had paid the minimal entrance fee, we asked the park attendant where we should camp. He said, “Just camp anywhere you would like,” which we found interesting. There was no designated campground.

Being able to “camp anywhere” sounds great, but in reality it can be pretty hard to find a suitable spot. In Parque El Tecuán, we didn’t want to camp near the cabins, so that was our first constraint. In addition, the landscape was very open and hilly - the pine trees were scattered very far apart, with tall grass growing on the slopes in between. It wasn’t going to be easy to find a flat spot with a little shade. We rode out to the end of the dirt road through the entire park, to a spot on the map that showed a small water body. But the pond was mostly empty, and looked like a mosquito breeding zone. So we decided not to camp there, either.

We finally decided to try out an area on a hillside that actually looked like it was meant to serve as a campground. There was even a car with a tent already there, although they left in the early afternoon. It took us a long time to find a spot level enough to pitch our tent. And in the end we had to settle for a location that still had a pretty strong slope. But we hoped it wouldn’t be so steep that it would keep us from sleeping.

Our campsite among the pines, on one of the less steep slopes. El Tecuán Ecological Park, State of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

With plenty of daylight left, we went for a walk among the pines. There were quite a few birds around, scratching for bugs and seeds among the pine needles and gravel. They seemed quite used to having people nearby, and would come very close to our campsite if we ignored them. But as soon as we tried to approach them, the birds would get a lot more skittish and keep their distance. Getting some good photos of the birds became a dance in which we had to pretend we weren’t really interested in them, while sneaking up on them anyway.

The night was very quiet, except for the call of a poorwill right after dark.

Arrival in Mexico’s Central High Plains

We had finally crested the highest passes of the Sierra Madre mountains. From Parque El Tecuán, the ride into the city of Durango would drop us more than 2,000 ft (610 m) from pine-clad peaks, down into Mexico’s central high plain. The forests were soon replaced by a more desert-like habitat sporting yucca trees, scattered thorny shrubs, and the impressive Durango giant prickly pear cactus.

But the ride was not all downhill, of course. We traversed two dry river valleys, each over 1,000 ft deep (305 m) with scorching, fun downhills where we hit speeds close to 40 mph (65 kph). Those were followed by slow slogs out the other side of the valleys, involving climbs of nearly the same height. Traffic was surprisingly light, even as we approached the big city.

Leaving behind the Sierra Madre mountains. Hwy 40 approaching city of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Our bikes enjoying a vista overlooking the Rio Chico, one of the steep valleys we had to cross on our descent out of the Sierra Madre mountains. Hwy 40 approaching city of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A hillside covered with Durango giant prickly pear cacti, which grow as big as trees. The species is endemic to a small area of the foothills in the Sierra Madre Occidental, in the general vicinity of Durango. Hwy 40 approaching city of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Woodpeckers were the most visible wildlife along this part of the route. We spotted several different species on roadside posts.

Our road heading into the second, steep-sided valley. Hwy 40 approaching city of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we crested the final ridge, we got our first glimpse of the broad central plain, with the city of Durango spread out below us. In the blink of an eye we plummeted down the final descent. And before we knew it, we had reached the outskirts of the city.

The fast and steep descent onto Mexico’s central high plains. Hwy 40 approaching city of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We made it to Durango, after nearly 23,000 cumulative feet of climbing (7,000 m) through the Sierra Madre mountains. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Upon entering Durango, we were able to cycle on a bike path that paralleled the highway. The path had its hassles - like lamp posts plopped right in the middle of the cycling lane, lots of cars and store fronts that were “temporarily” making use of the space, and some sketchy road crossings with cliffs (i.e., 2 foot high curbs) - but it still was a great alternative to cycling on the now very busy highway. We started to think we might sail into Durango without any major headaches.

But that was not to be. Two miles and 20 minutes later, the bike path disappeared just as we entered the older urban center, with much narrower roads and no shoulder to ride on. The final 2.5 miles (4 km) were a scramble on busy roadways with lots of weaving traffic, and sidewalks that were full of pedestrians and other barriers. We occasionally had to get off our bikes and fit them between sidewalk vendors and other obstacles that left just enough room to squeeze through - with one or both sides of the bike rubbing a building or some other obstruction. We were greatly relieved when we finally arrived at the Plaza de Armas, the heart of Durango’s historic district just a stone’s throw away from our hotel.

Taking it Easy in Durango

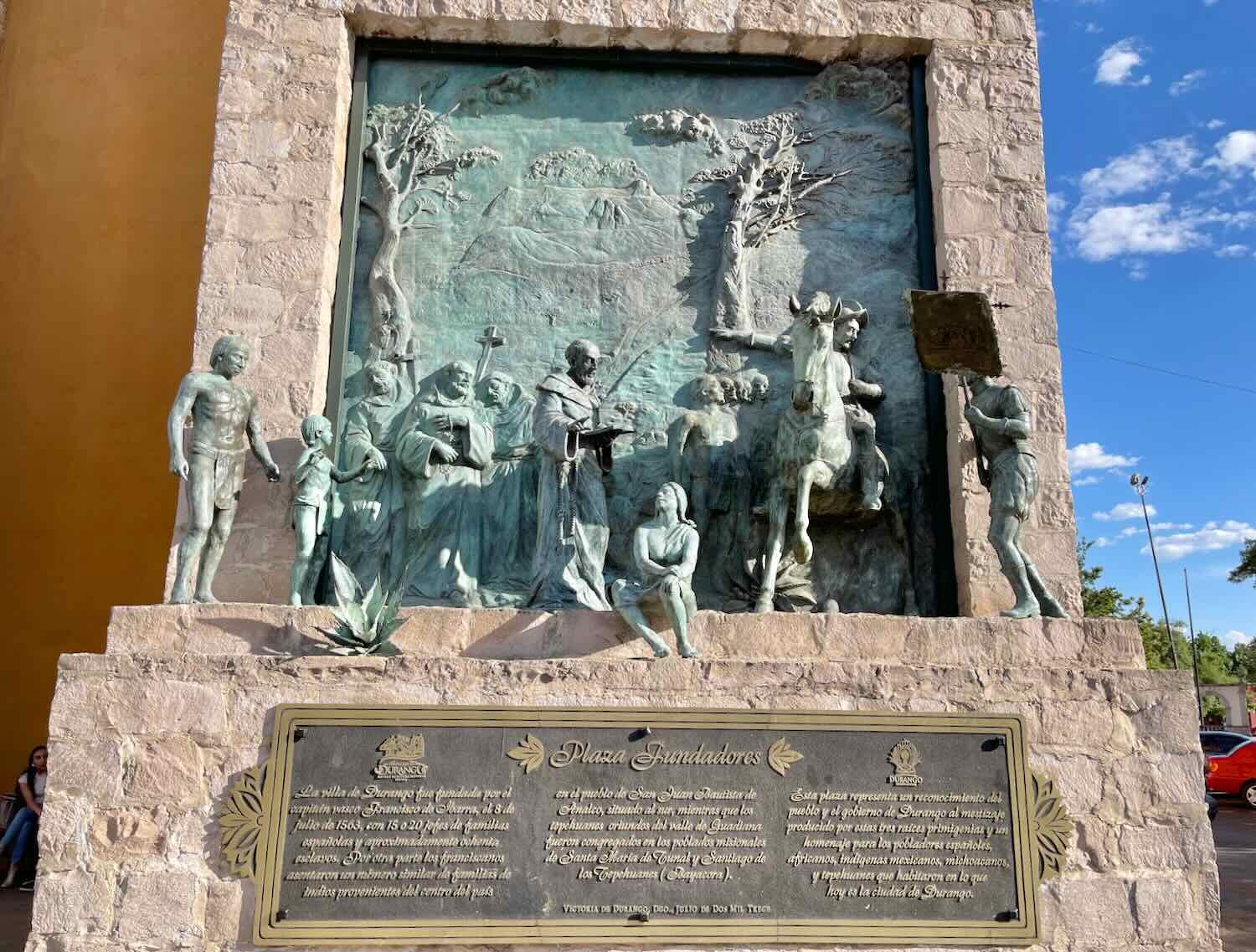

We spent the next few days hanging out in Durango, enjoying the sights and sounds of this lovely, colonial era city. The city was founded more than 450 years ago when the Spaniards discovered gold, and especially silver in the surrounding mountains. As is common in Mexican colonial towns, the cathedral forms the centerpiece of the historic district. Construction of Durango’s cathedral began in the 1690s, but it took 150 years to complete. A popular legend says that one of the bell towers is haunted by the spirit of the nun Beatriz, whose doomed love affair with a French soldier led her to commit suicide by throwing herself from one of the towers when he failed to return for her (he had a good excuse - he had been killed by the Spanish).

Our hotel was an old, converted convent adjacent to the cathedral. We have stayed in converted convents and monasteries in the past, and love it. You can be in the middle of the busiest and noisiest city, and the hotel will be a perfect refuge of peace and tranquility. With walls of stone that were 2-4 feet thick, the hotel was cool and quiet despite having one of the most crowded and hectic streets in town right outside the front door. Unfortunately the thick walls made for challenging internet reception, but it was a worthwhile tradeoff.

Evening light on the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. The ghost of a nun still haunts one of the bell towers. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Most mornings we would go for a long walk before the day got too hot. That gave us a chance to explore Durango’s numerous plazas, the famous Calle Constitución (a pedestrian street lined with shops), and to climb a nearby hill to admire the city from above. Despite its many attractive features, Durango is not a big destination for foreign tourists - we didn’t hear any English spoken on the street like we did in Loreto, La Paz, and Mazatlán. Most of the visitors appeared to be from other parts of Mexico.

A fountain in the Plaza de Armas. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Balloons and other toys add a splash of color in the Plaza de Armas. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A nickname for Durango is the Land of Cinema - due to the fact that more than 130 movies were filmed there (especially westerns). The walk of fame honors Mexican and Hollywood celebrities that worked on these movies. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Calle Constitución, Durango’s colorful pedestrian street, is always packed with Mexicans out for a stroll. It’s not the kind of street that sports high fashion or name brands. Instead it was lined with local businesses, bars and cafes. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The Church of San Augustín, at one end of Calle Constitución. Early in the morning, the street was practically deserted. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A morning climb up the Cerro de los Remedios (the Hill of the Cures). Climbing these stairs each day helped keep us in shape during our layover. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

View of Durango from the heights of the Cerro de los Remedios, on one of the few cloudy days we’ve had in the past few months. City of Durango, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Another Side of Mexico

After spending more than three months in Baja - where many of the villages had fewer than 100 people, and most of the landscape was very sparsely populated (typically requiring 2-6 days of cycling between towns where we could replenish our supplies), mainland Mexico was a whole different experience. Both Mazatlán and Durango are twice as big as La Paz. And during eight days of cycling, we always seemed to pass at least one town (often more) with a little shop where we could rest and find a cold drink. Opportunities to wild camp were much less frequent, replaced by small town hotels that typically had just the most basic facilities.

But the scenery was spectacular. Nothing quite rivals the mountain vistas of the Sierra Madre, with its astonishingly steep slopes that form jagged ridges stretching to the horizon. And we’ve thoroughly enjoyed our encounters with a whole new suite of wildlife - some of which begins to evoke the the exotic shapes and colors of more tropical species. Moreover, the people in the mountain communities were kind, generous and welcoming. The crossing of the Sierra Madre mountains has been another epic adventure in our journey south.