Baja Divide Part 4: Cycling from San Ignacio to Mulegé

15 - 22 March 2023

Baja Divide Section #12

15 March - San Ignacio to Laguna San Ignacio (41.8 mi, 673 km)

16 March - Layover in Laguna San Ignacio

17 March - Laguna San Ignacio to Wild Camp, El Batequi (48.1 mi, 77.4 km)

Baja Divide Section #13

18 March - Wild Camp, El Batequi to Wild Camp N of Rancho Girasole (26.4 mi, 42.5 km)

19 March - Wild Camp N of Rancho Girasole to Wild Camp S of San Miguel (17.3 mi, 27.8 km)

20 March - Wild Camp S of San Miguel to Mulegé (34.8 mi, 56.0 km)

21-22 March - Layover in Mulegé

Salt and Sand

We had enjoyed our layover day in the charming mission town of San Ignacio. Its tranquil plaza and historic church were both lovely. But San Ignacio’s biggest claim to fame is the fact that it serves as a jumping off point for visiting one of the best and most famous places in the world to see gray whales - the San Ignacio Lagoon. And as luck would have it, the Baja Divide route goes right past the prime whale-watching beaches, which lie a little over 40 miles (64 km) south of town. During our stay in San Ignacio we had secured our reservation for a whale-watching tour. Now all we had to do was cycle across 40 miles of coastal desert to the tour company’s campground.

The ride out of town began with a heart-pumping, one-mile, 300 foot climb out of the oasis valley and up onto a parched mesa. It’s always a shock to your system when you have a steep climb at the very start of a day’s ride. On the other hand, there’s definitely something to be said for getting the hardest part over quickly (and in the coolest part of the day). Surprisingly, the section of the road through town was rough dirt. But as soon as we reached the last house at the edge of town, we were back on pavement. And for the next 30 or so miles (48 km) we cruised along on smooth black top.

The high quality of the road makes it easy for tour companies to shuttle whale-watchers back and forth. So it wasn’t surprising that we were passed by a number of minivans hauling prospective visitors out to the lagoon. After an hour and a half, we reached the small settlement of San Zacarías (pop. 6) with just a couple of buildings clustered around a bend in the road.

An attractive, lovingly-maintained chapel across the road from the other buildings was the first thing to draw our attention when we arrived at San Zacarías, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We had skipped eating that morning to help us get as early a start as possible, maximizing our cycling time in the cool morning hours. So we were counting on the small store in San Zacarías for breakfast. It was not a good feeling when we pulled up to the store, only to discover that the door facing the road was padlocked shut. But all was not lost. A bit of exploring confirmed that there was another door on the side of the building, and it was open.

We went inside, but no one was there. We started looking around, hoping someone would eventually show up. And sure enough, pretty soon a guy came over from a nearby house to help us. And before you could say “cookies and cold drinks,” we had procured enough food to get us through the afternoon. These little stores usually have ample cookies and baked goods, but very little other than carbohydrates and sugar (unless you don’t mind eating refried beans or tuna for breakfast).

We ate our energy-rich breakfast on the concrete wall outside of the small, roadside store. San Zacarías, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Two and a half hours later we reached the end of the pavement. From there, we rode out onto a hard-packed, dirt levee that cut a straight line across barren salt flats. The surface was not as smooth as we had hoped. Given the high volume of vehicles using the road, there were a lot of rocks, potholes and washboards that rattled our teeth and slowed us down considerably for the last 10 miles (16 km).

The dirt road cut a nearly-straight line across the otherworldly salt flats. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The salt flats, known as the Salina el Cuarenta, created a fascinating landscape. Here, at the northern end of the lagoon, mineral-rich water that flows down from the surrounding mountains evaporates faster than it can sink into the ground or flow out to the sea - leaving behind a cocktail of salts and minerals that form a crust over the mud below. Depending on its chemical composition, the crust can vary in color from snowy white (pure sea salt) to cream colored or even rusty brown.

Mineral-rich salt flats of the Salina el Cuarenta, with the Sierra Santa Clara in the distance. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

In several spots there were ditches along the side of the road that still contained water. The hyper-saline pools were a rich, rusty brown color. Their edges were crusted with snowy white salt crystals that glistened in the sunlight. It was a stark and fascinating landscape, with virtually no visible wildlife or plants.

Wherever water collected on the side of the road it had a rusty-orange color, with a halo of bright, white rock salt. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Close-up of the rock salt fringe on a mineral pool. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The ride across the flats went on for nearly 10 miles (16 km). Here, we still have 14 km to go. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Eventually we reached the edge of the actual lagoon, and a tiny settlement along the shore that hosted another, small store. With only about five miles (8 km) left to ride, we just bought a couple of drinks to keep ourselves hydrated and cool off a bit. As we were sipping our drinks on a step outside the store, the proprietor came out to ask if we needed anything else. He was going to close the store and go fishing.

In the United States, if someone closes their store to go fishing it usually means they are going to take the afternoon off and relax by a lake somewhere. In this case, fishing was probably his second job or an important source of food. These remote stores almost never post their hours and it can be rather unpredictable as to whether they will be open, even in the middle of the day. You never know when the person who runs the store will be sick, on vacation, out buying supplies, or need to go fishing. This can present challenges to cyclists who often are dependent on these stores for resupply. You quickly learn to not use the last of your water or food before making sure you can actually get more at the next store down the road.

The store on the shores of Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It actually took a bit longer than we expected to get from there to the campground. The hard-packed dirt of the salt flats was replaced with sandy washboards that really slowed us down. It was a relief to finally arrive at the little compound run by Kuyima Whale Tours, and leave the bumpy roads behind.

After checking in at the campground’s main building (which also houses the restaurant), we went over to the water’s edge to pitch our tent. The wind was blowing pretty hard off of the water. Later we would come to realize that Laguna San Ignacio is a very windy place, pretty much all of the time. But we hadn’t been there that long yet, so we didn’t appreciate how much the wind would be a factor in our visit.

The restaurant and registration office at Kuyima campground. It was basically the only indoor space in the compound. So in addition to eating our meals there, we would also hang out at a table inside to escape the sun and wind. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

There were no trees or other wind breaks in the camping area. We were perched on a low bluff directly adjacent to the bay, receiving the full force of the wind off the water. After pitching the tent, it was clear that more stakes than normal would be required in order to prevent the tent from becoming a kite and flying away. In such moments we are reminded of the fact that Dyeema (formerly called cuben fiber), the material our tent is made from, is also considered one of the best materials for making boat sails. In our current situation, we seemed to have a better sail than tent.

In addition to adding more stakes, we decided to re-pitch the tent lower to the ground to reduce the gap where wind could blow through around the base. But re-pitching the tent turned into quite an ordeal because we had to pull up the stakes that we had already driven into the hard ground. Every once in while you find yourself in a place like this where the stakes seem to go in just fine, but won’t come out. The strong, constantly blowing wind did not help. Eventually we won the contest between us, the wind and the ground. There were a few broken and bent stakes to show for our efforts, but we felt much more confident that the tent would hold up to whatever wind the lagoon would send our way.

Our campsite by the lagoon. It may look calm, but the wind was howling. We used four extra guy lines to help hold the tent steady. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The campground boasted flush toilets and hot showers, but there was a catch. Neither of these facilities operated exactly as you might expect. In the bathroom stalls, there was a bucket of water with a large cup. To use the toilet, you scooped a cup of water into the toilet bowl before doing your business. When you were done, you’d step on a foot pedal to send everything down a drain into a tank below. To shower, you filled a bucket with hot water from a solar heated tank outside, then took the bucket with you into a private shower stall. The stall had a drain in the floor, and you poured cups of water over yourself to get wet, or to rinse. It was definitely low tech and we had our doubts, but it worked surprisingly well.

The brilliant colors of the sunset as seen from our campsite. A company employee told us that he loved the sunsets over the water, because they were spectacular every night. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A Rendezvous With the Whales

Contrary to our hope for a lull in the wind, an incredibly fierce gale blew throughout most of the night. Even with the four extra guy lines, the tent heaved and rattled for hours. Around 1 am PedalingGal put in earplugs to try to block out some of the noise. A couple of hours later PedalingGuy went out of the tent to tighten the guy lines. That helped reduce the racket made by the tent’s fabric, but the wind kept pummeling us until after sunrise.

We were up and out in the early light, eager to be on the first boat out to the whale viewing area. We had prepped our gear the night before, so we were able to get ready quickly. We headed over to the restaurant as soon as it opened - not to eat breakfast, but to let the staff know we were prepared to go as soon as a boat was ready.

The Sierra Santa Clara as seen from our campsite in the morning light. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One of the rules of the boat tours is that they require a minimum of four people for a tour. So even though a boat could theoretically leave at 8am, we had to wait for at least two other people to be ready to go with us. At 8am, the staff were still serving breakfast to several other groups of guests. It was clear that there wouldn’t be any boats going out until at least a couple of other people finished eating. We sat at a corner table, biding our time, with only the whale on our napkin holder to entertain us.

The napkin holders in the campground restaurant depict various images of gray whales. Our table had the head of a whale, posed as if it were poking up out of the water. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Finally, after what seemed like a really long wait, three guys from Venice, Italy, were ready to go out on a boat with us. We were given a briefing that included a little bit of information about the lagoon, the biology and behavior of the whales, and what we could expect on the tour. Apparently you can encourage whales to approach the boat by splashing the water with your hands, or by singing. (Note: it is unknown whether the singing really brings in whales, or is just folklore meant to entertain the boat captain. But apparently the splashing really works.)

Everyone is required to attend a briefing by the team biologist before going out on a boat. The palapa where they give the briefing has an image of a whale next to a person (to show how big they are), plus a map of the lagoon. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The wind had died down a bit, so the boat ride out to the whale viewing area was not too choppy. And once we arrived at the whale viewing area, the seas were very calm.

Riding out to the whale-watching area. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A guy from the national park service monitored the number of boats entering the whale-viewing zone. They limit the number of boats that can be near the whales at any given time. There’s also a 1.5 hour limit on how long any one boat can be within the zone. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Early in the ride we spotted a California sea lion that had caught a flounder. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The main attraction here is the gray whales. They spend their summers feeding in the northern Pacific Ocean, especially the seas around Alaska. In the fall, they migrate down the coast to several shallow bays in Baja where they spend the winter - having babies and mating. By late March, the whales are on their way back north. Astonishingly, the whales eat little if any food throughout the entire 10,000 mile (16,000 km) migration and winter calving season. They eat almost all of their food for the whole year during the summer months in Alaska.

One of the best places in the world to see these gentle giants is in the bays of Baja, where they give birth, socialize and mate between the months of January and March. And Laguna San Ignacio offers some of the most intimate and rewarding experiences with gray whales, even compared to other sites in Baja. There can be hundreds of whales present over the winter, and some of them will curiously approach the boats to actually interact with the humans on board.

Our tour was a wonderful experience. We saw dozens of gray whales, and we could typically see them blowing spouts of water into the air in every direction. Some of them came very close to the boat, including some mothers with young, and some very big whales - probably males. It was awe inspiring to see groups of whales engaged in social behavior, including log rolls, raising their flippers and even their heads out of the water, and one, exciting, full-splash breach.

Whales in this large group nuzzled each other and rolled in the water very close to our boat. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

This whale lifted a flipper out of the water. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Another whale raised its head until its eye was above the water line. They call this “spy hopping,” and yes, the whales do it so they can see what’s going on above the water. The whale probably wanted to see who was in our boat. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The blow hole and barnacles on a large whale. Gray whales get particularly crusty - they carry a heavier barnacle load than any other species of whale. At least one of the species of barnacles is found only on gray whales, and nowhere else. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It’s not easy to capture a breaching whale on camera. It happens really fast. We just managed to catch this one in the act. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The absolutely most exciting thing that can happen on one of these tours is for a whale to approach your boat. We were among the lucky ones. A small whale - probably one of this year’s new calves - came right up to our boat. With its head next to the hull, it rolled over on its side to have a look at PedalingGal. But she was unable to touch it. Some whales like to be petted and scratched, but this one remained just out of reach. A different whale lifted its head out of the water next to another boat, not far from ours, giving us a great look at its face.

The folks on another boat got an even more personal visit from a different whale. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

After an hour and a half in the whale viewing area, we were required to head back to shore. It had been an incredible experience.

We spent most of the rest of the day in the campground restaurant, staying out of the heat and wind. In the early afternoon we briefly tried resting in the tent. But even with the wind it was just too hot. So we headed back to the restaurant.

After dinner we went for a short walk out to the main road. It’s a very barren landscape, and there was not a lot to see. But there was one thing that caught our attention. There are thousands of piles of scallop shells scattered across the land for miles. They are the legacy of a shellfish boom that virtually emptied the lagoon of scallops in the 20th century. Today there is a small, local scallop fishery, but the shellfish have not fully recovered to their previous abundance.

Piles of scallop shells surrounded the Kuyima campground as far as the eye can see. Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

On the first night in the campground we had been the only ones to pitch our own tent (other guests stayed in the sturdy, semi-permanent, canvas tents that you can rent). But on the second night we had quite a bit of company.

There were three camper vans, plus a couple that had arrived on motorcycles. Adrian and Jenn, the motorbikers, ended up camping next to us. And they had an UltaMid 4 tent, just like us. When we started chatting with them, it was clear that we shared a lot of interests. We talked for a long time about bicycles and bike components, tents, other gear, backcountry routes through Baja, long distance cycling and more. They were brimming with enthusiasm for their journey, and had just come in from the direction we were planning to head out the next day. Their excitement was just the thing to get us revved up for heading back into the mountains.

As we went to bed in the darkness, the wind was howling again. It was easily blowing at 20+ mph, with gusts much, much higher. The tent was heaving and creaking. Then, in the darkness, we heard PedalingGal’s bike fall over - toppled by the wind. Drat. We went outside and laid PedalingGuy’s bike down so it wouldn’t tip as well. Then we collected some of the items at risk of blowing away, like our helmets and empty water bottles, and brought them into the tent for safe keeping. We hoped that would be sufficient to keep us from losing any gear during the night.

Rolling With the Wind

It was a blustery night. The wind howled like crazy for several hours after dark. Then it would calm down, only to whip up again. Topping things off, a few, scattered raindrops fell on the tent right at dawn.

Needless to say, taking down the tent was an adventure in itself. It was like trying to fold up a miniature boat sail in a storm. Anything that was not firmly secured was at risk of blowing off across the desert, never to be seen again. To help maintain control of the tent, we unhooked it from the stakes, without taking the stakes out of the ground - a departure from our regular routine. In the end, we managed to get the tent folded and put away. But at a price.

Over the past nine months we had settled into a very specific process for taking down the tent. That made us efficient, because each morning we both knew exactly what to do, and in which order, so that every task was completed without any need for discussion and nothing was forgotten. By varying our routine this morning, we increased our risk of making a mistake - and that’s what happened. We forgot to go back and pull up those stakes after folding the tent - leaving them in the ground. They were thin and silver, making them practically invisible against the gravel. So when we checked our campsite to make sure we had packed everything before leaving, we didn’t see them. It wouldn’t be until the end of the day, when we were setting up our next wild camp, that we would realize that our favorite, titanium, shepherd’s hook stakes were gone. By then it would be much too late to find a way to get them back. With more bent, broken and lost tent stakes from this one campsite than from the previous nine months of camping, we were glad that most campsites were not so difficult.

But as we left the campground in the morning, we didn’t have tent stakes on our minds.

We made our way to the little store in the town of Ejido Luis Echeverria for breakfast. As we were eating some muffins on a couple of plastic chairs outside the store, it started raining. And before we knew it the rain was coming down pretty hard. That sent us scuttling back into the store to finish our meal while standing in a corner, trying to stay out of other people’s way. We wondered aloud if the rain would ruin the road surface, and if we would have to head back to the campground on the lagoon. But soon enough the rain ended, and things dried up quickly. We decided to go for it. For the rest of the day it remained cloudy and cool, but that was the end of the rain.

For most of the way to the coastal village of El Datíl we rode on hard-packed salt flats with the wind at our backs. - making for a fast, fun ride. But every so often we had to cross shorter stretches of sandy dunes. Most of the time the sand wasn’t too bad. But there was one section of about a mile that was very deep and soft. As we were pushing our bikes and starting to think about airing down our tires, we decided that we’d just try to get to the top of the next rise before making any changes. It was the smart move. Right after cresting that hill we were back on the hard-pack.

Racing down the smooth, hard-packed track across the salt flats. South of Ejido Luis Echeverría, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A loggerhead shrike was one of the few creatures we saw in this empty, windy landscape. It was perched on a brush pile on one of the sand dunes. S of Ejido Luis Echeverría, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Dumping sand out of shoes became a regular activity. South of Ejido Luis Echeverría, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Salt-encrusted mud flats covered the landscape between us and the Pacific Ocean. South of Ejido Luis Echeverría, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

At a remote crossroads near an abandoned building, a line of decaying telephone poles provided nesting habitat for an astonishing number of ospreys. There was an active nest on almost every pole. Only about half of the poles and nests that were present could fit in this picture. Fishing must have been pretty good around there to support so many ospreys in close quarters. Los Batequis, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A cardboard sign near the crossroads helps travelers get their bearings. We’ve really come to appreciate these makeshift signs in the middle of nowhere. Los Batequis, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The fierce winds that had plagued us on the shores of the lagoon now became our friend. We had a very strong tail wind most of the day. As a result, we flew across the miles. We often cruised along at 15+ mph, hitting top speeds over 20 mph (32 kph). It was a blast.

With the wind at our backs, we flew across the salt flats at 15+ mph. Approaching El Datíl, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

In theory we had entered an ecoregion dominated by mangroves as soon as we left the town of Ejido Luis Echeverrria. But for the first 5.5 hours of the ride, all we saw was mud, sand dunes, and bunchgrasses. The only place we saw any mangroves was in the immediate vicinity of the village of El Datíl. As we rode into town, a low, dense forest of mangroves hugged the shore close to the road.

The mangroves bordering the road in El Datíl were the only ones we saw. And these were only about chest-high - very short for mangroves. El Datíl, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

El Datíl had a very different vibe to it than any other small town we had yet visited in Baja. It was bustling with activity. As we rode through the town, we passed fishermen unloading the day’s catch from their boats, and lots of other folks out and about. Kids shouted to us, asking if we wanted to buy a meal from their homes. But we didn’t see anything that looked like a store. That was a problem, because we needed to pick up supplies for the next, multi-day stretch of backcountry cycling.

When we reached the far end of town, a guy in one of the houses asked us if we would like to buy some clams - and offered to cook us clams for dinner. But that wasn’t what we were hoping for especially since, if there was a store, we needed to buy supplies before it closed. So we said, “no gracias,” and turned around, heading back into town.

As we cycled slowly down the main street, a young kid ran over and asked if we would like to have dinner at his house. That sounded nice, but we were still looking for the store. So we asked him where the store was, and he insisted that there wasn’t one. That was weird, because we had read online that there really was a store. Finally, an older guy came out of the house, and showed us where the store was. It was only a couple of buildings away, but it was very low key. You entered through a dark, unmarked door adjacent to an old, semi-truck container that was full of groceries. There were no signs indicating that there was a store, probably because everyone in town knows where it is and the town does not get many visitors. No wonder it was so hard to find.

While PedalingGuy shopped, PedalingGal waited outside with the bikes. Soon, a group of kids had gathered around to investigate. It started to feel a bit like Africa, where whenever we rolled into a town groups of children would come running over to check us out. We hadn’t had this happen anywhere else on our current trip. Yet the kids were clearly curious, asking questions about our gear and what we were doing. Our arrival was definitely a source of entertainment - something new and exotic in their day.

Once our shopping was done, we decided to go back to the house of the guy who had helped us find the store, where the kid had offered us a meal. They were very welcoming, and his mother proceeded to cook us a big meal of fish strips, haba beans (a.k.a., fava beans, the same kind that are popular in east Africa), rice and limeade. It was a hearty meal and the price was very fair. The kids joined us for lunch, and we chatted with them about school and their village. It turned into a very pleasant visit, and we appreciated their hospitality. Then we got back on our bikes and headed out of town.

Not long after leaving El Datíl we spotted a couple of crested caracaras harassing an osprey, causing it to drop its fish. Here, the caracaras stand guard over the fish they’ve just stolen. Southeast of El Datíl, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We ended up crossing one more, short stretch of deep sand on the flats. As we neared the far end of the dune, we came upon a small car stuck in the sand. And it was really, very stuck. The front tires were buried in sand up over the hubs. It didn’t look good. Even a 4-wheel drive vehicle would have had a hard time making it though the sand in that spot. Six guys were trying to rescue the car, with two of them actively digging out one of the front tires. It was hard to imagine them being able to free that car with the tools that they had, but people do become resourceful living out in this remote landscape. An older lady was watching, and we wondered if it was her car. We stopped and asked one of the guys if they would like us to stay and help, but he said, no. So we headed on down the road.

After more than 40 miles of cycling we finally left the mud flats for good. Unfortunately, we then had to contend with an extended stretch of deep sand, with lots of bike pushing. But just as we were starting to consider airing down the tires for the second time that day, the route climbed out of the sand and onto a rocky road. That’s pretty typical for the Baja Divide. The road conditions often seem to change suddenly, just when you think the current sand, rocks or other obstacles are going to go on forever.

Toward the end of the day our route left the coastal flats behind, and started to climb into the foothills. A herd of goats indicated we were back in ranch country. Goats are able to survive better than most animals in this harsh environment and are the most common animal we saw on ranches. El Batequi, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

After nearly 50 miles of cycling, assisted by the wind across the salt flats, we finally called it a day. It had been an fascinating ride with strange and unique landscapes - one that would stand out among all the other days of cycling on the Baja Divide. We followed a dirt side track away from the main road, and camped in an opening not far from a dry wash. White sandstone cliffs provided a scenic backdrop for our evening.

Our campsite near the white, sandstone cliffs at El Batequi, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It was when we started to pitch the tent that we realized we’d lost the shepherd’s hook stakes back at the lagoon. That was a real bummer, and it crashed our good mood at the end of the day. We had to change how we pitched the tent, because our other stakes were all too thick to fit through the loops on the mesh inner tent. We found a temporary fix, but it wasn’t ideal and we would need to figure out a better solution going forward. At least we were able to put up the tent. But we were both out of sorts after that. Fortunately, the wind died down in the evening. We were very glad to be away from the crazy winds at Laguna San Ignacio.

A Fix for Our Tent

Over night PedalingGuy came up with a solution for pitching our tent without the shepherd’s hook stakes. We had been carrying a length of thin, high-tension line that we actually considered getting rid of at one point, because we hadn’t needed it for anything yet. But it turned out to be the ideal rope for tying loops onto the corners of the inner mesh tent. We made the loops big enough to work with our remaining, aluminum stakes. The rope is lightweight, thin and soft (so it won’t damage the mesh when the tent is rolled up), but also very strong. We took the time in the morning to tie the loops onto the tent and test them for strength, and they worked perfectly. Problem solved. We both felt a lot better after that.

The other issue that had been plaguing our tent was that the zippers were getting worn out, and starting to fail. One of the zippers had become very difficult to close without the teeth pulling apart afterward. So while we were in maintenance mode, PedalingGal also took the time to clean the zippers. We have found over the years that fine sand and powdery dirt, something there was plenty of in Baja, can wear out tent zippers really fast. We would probably have to get replacement zipper sliders at some point, but how to accomplish that was a big, open question.

Cycling Along an Arroyo

Our day started with a climb. Within the first half mile we ascended the face of the white cliffs, up and onto the top of the mesa.

A flock of lark sparrows watched curiously as we cycled toward the cliffs. El Batequi, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The ride up onto the mesa was steep enough to get our hearts pumping. But on the way up we got some extra motivation to tackle that hill as fast as we could. About three quarters of the way up the hill, we were ambushed by a wild colony of honey bees. PedalingGal was attacked first. Initially she thought it was a swarm of flies or beetles, as the insects started crashing into her panniers. Then one stung her hand. She shouted to PedalingGuy to hurry, as she stepped on the gas, laboring up the hill as fast as she could go. But instead of speeding up, PedalingGuy (who has worked with honey bee hives in past and is a little cavalier with bees), slowed down to try and help. Pretty soon he got stung on the wrist as well. We both were surprised by how aggressive those bees were, compared to our past experience with honey bees. We wondered if they were Africanized honey bees, which have been a concern in Mexico.

When we finally made it to the top, we had left the bees behind. And fortunately, we each had only one sting. But we hadn’t been able to stop to pull the stingers out until we reached safety, so we both got an extra dose of toxins. PedalingGuy remarked that he had never seen PedalingGal ride up a hill so fast. At least we had a beautiful view of the broad floodplain from the top of the hill.

View of the Arroyo Las Vacas Valley, where we had camped the previous night. We stopped at the top of the mesa to pull bee stingers out of our hands. El Batequi, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We had just started riding again after the bee episode, when we saw another cyclist coming the other way. In the last 3 months we had only seen one other touring cyclist going in the opposite direction from us, so this was unexpected. Alain was from Switzerland, and had been cycling in Mexico for nearly a year. We talked with him for a long time, learning about his experiences on the Trans-Mexico Bikepacking Route, which we plan to ride after completing the Baja Divide. He was hoping to cycle all the way to Deadhorse, Alaska, so we had lots of tips for him as well. We let him know about the bees. But he would be going downhill, so hopefully he could outmaneuver them. Eventually we said goodbye, and headed down the road.

At first the road conditions were pretty good. However, once we turned off of the mesa and headed into the mountains, the surface got a lot rougher. For the next 35 miles (56 km) the route would slowly wind its way uphill by following the path of a wide, mostly dry, desert arroyo. Along the way, it would weave back and forth across the floodplain - sometimes plowing through deep sand banks that lined the waterway, sometimes grinding over cobblestones deposited in the dry river bed, and sometimes crossing wide, shallow pools where last year’s rainwater had not yet evaporated or sunk into the ground.

Even with these obstacles, we made pretty good progress for most of the day. We were able to cycle over almost all of the rocks and sand, except for the occasional water crossing or particularly rough cobblestones.

One of the early dry-river crossings. This low in the foothills, the river channel was huge and the cobblestone river bed could stretch for more than a quarter mile (0.4 km). Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

2022 had been a particularly wet year in Baja, so water in the river crossings was often a foot or more deep. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

With all the water on this part of the route, some cyclists had recommended relying on filtered river water rather than carrying extra. But this was definitely ranching country, and there was evidence of cows, goats and horses everywhere. One thing you can be sure of when traveling in the desert is that if there are range animals around, they will know where the water is. And they likely will contaminate it, unless the water is fenced off. In fact, one of the reasons why this area was being used for ranching was probably due to the availability of water, which is a lot more scarce in other parts of Baja. Consequently, even though we traveled with a filter, we preferred to carry all of the water we were going to need. The extra weight probably slowed us down, but it also gave us peace of mind.

Cows were a common sight along the route. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

These two horses were hanging out along the edge of a water hole. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It was mid-afternoon when we finally arrived at Rancho Girasole, the first of several ranches along the Baja Divide back roads where the owners welcome cyclists into their homes. These aren’t full-blown businesses like the two ecotourism ranches between Bahía de los Ángeles and Vizcaíno, where we had stayed in cabins and eaten in restaurants. Instead they are more like informal homestays where travelers can rest, have a drink, eat a meal, and even camp if the timing is right. Some, like Rancho Girasole, have signs out by the road encouraging cyclists to stop and visit. How could we resist.

As we rode up we were greeted by two white puffballs of dogs, and lots of tail wagging. Pretty soon Jesus and María appeared and invited us in to a pleasant, palapa-covered sitting area. María asked if we would like something to drink (yes!), and whether she could prepare us a meal (double yes!). As María cooked omelettes with rice and homemade tortillas, we visited with Jesus and sipped cold drinks under the palapa.

We learned that they had been living on the ranch for nine years, and that they kept small herds of cows and goats. Prior to moving to the ranch, Jesus had worked in several different jobs including fishing on a boat out of El Datíl and working in the construction business. They had three sons, all living and working in cities to the south. They seemed like really sweet people.

Then María invited us into the kitchen of their home to eat. The meal was delicious and filling - a huge boost to our day. And having the chance to rest in the shade while visiting with Jesus and María was a huge bonus. We spent about an hour at their house. It felt like such a privilege to be able to share that time with people we would probably not otherwise meet. We were glad that they seemed to enjoy it as well.

Jesus and Maria opened their home to us, as they have for other cyclists on the Baja Divide. Rancho Girasole, Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Afterwards, it was a bit tough to go back out into the afternoon sun. But there were still a couple of hours of daylight left, and we wanted to get as far down the road as we could.

In anticipation of getting our feet wet, we had both worn sandals that day. By the end of the day we had gone through two water crossings. Both of them were about a foot deep, so we ended up walking across. Luckily, with the hot weather, wading through the water was actually quite pleasant. We certainly didn’t have to worry about getting cold.

Our second river crossing. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

When you wear sandals out on the trail, a lot of grit, stones and sand gets in. Every so often we had to top and dump it all out. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we followed the arroyo upstream and gained elevation, the valley got narrower and the white cliffs inched closer. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The cycling became much more difficult after Rancho Girasole. The biggest factor was that the road surface deteriorated dramatically, and seemed to take delight in crossing back and forth across the rocky river channel. In addition, the route launched over a steep ridge less than a half hour after leaving the ranch. From the top of the ridge we could see the wide floodplain snaking away from us, with an isolated, blue pool of water in the channel.

View from the top of a ridge, before descending back into the river valley. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We managed to bike another 5+ miles before deciding to stop for the night. After investigating a couple of side roads we found one that led back into the trees, to a sandy area along the bank of the river. There was water in the channel, so we enjoyed a lovely dinner sitting on the river bank as the sun went down. But as darkness set in, a few mosquitoes appeared sending us into the tent for the night. A western screech owl serenaded us as we drifted off to sleep.

A Canyon Into the Mountains

We woke up at dawn and packed up our sandy camp. We were extra careful to make sure we got all of the tent stakes, since we now had none to spare. One or more of the stakes could easily have disappeared under a carelessly kicked pile of sand. Adding to our challenges, the bee stings from the previous morning had swollen up a lot. Each of us had a very puffy left hand, and the swelling was extending up PedalinGuy’s arm. Having been stung by honey bees many times in the past, PedalingGuy wondered why his reaction was so much worse than any previous stings.

It turned out to be a surprisingly hard day. We only covered about 17 miles in seven hours of cycling (one of our shortest days on this trip), and it was exhausting. There had been only two water crossings the day before. On this day there were 14 water crossings - nearly one per mile. On top of that, there were easily 30+ additional dry riverbed crossings with large rocks that were just as difficult. All day the road surface alternated between loose and sometimes very large cobble stones and deep, soft sand. For us, much of the road was unrideable, so we were constantly getting on and off of our bikes. Some have called this one of the most difficult sections of the Baja Divide Route.

Another mile, another water crossing. Piles of rocks mark the line of the road for passing vehicles. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Sometimes we could ride on the dry riverbeds, especially if the rocks had been packed down. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But more often the rocks were scattered in loose piles that threw our bikes in multiple directions when we tried to ride across. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One of the best things about cycling in the valley was that the trees were often big enough to provide some shade, keeping us from getting too overheated. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Although the riding was difficult, the canyon we were riding in was very scenic. There were towering cliffs and majestic buttes quite close to the road. As we approached Rancho Riconada, the scenery became particularly beautiful as the canyon walls closed in on the valley.

As we headed further up and into the canyon, the valley got narrower and was lined with majestic stone buttes. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

And the river crossings kept coming. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A big motivator in keeping us moving was the promise of reaching another well-known ranch, where the friendly owners welcome bicyclists for a rest. We had expected to cover the 13 miles (21 km) to Rancho Riconada by mid-morning. But that was wishful thinking. Instead, we dragged ourselves into the ranch’s little courtyard around 2:30pm. This ranch was much more low-key than the first one. There was no “welcome” sign out by the road. And the house was perched high above the river bed on a steep hill - clearly to keep it safe from seasonal floodwaters. Nonetheless, as we approached, we heard a welcoming, “Hola, buenos dias. ¿Quieres comida?”

It was tough pushing our bikes up that last hill to the ranch, but it was worth it. Carmelo and Rosalina welcomed us warmly. They had a sturdy table and benches in the shade of a palapa where we were able to sit and visit. We learned that they were goat ranchers who get all of their food from their own land, so the meal was much more simple than at Rancho Girasole. Rosalina served us homemade limeade, and cooked us a big plate of bean burritos with goat cheese.

Carmelo and Rosalina’s get everything they need from their ranch in the mountains. A pretty big herd of goats provides milk for cheese. Rancho Riconada, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Carmelo was very friendly, and did his best to speak with us in our limited Spanish while Rosalina cooked. The only exit from their house to the road crossed one of the main river channels, and we asked whether flooding was a problem. They said that the rainy season runs from August to November, and they are typically marooned for two months each year when the road becomes impassable. But the isolation doesn’t bother them. It was clear that they love the quiet life on the ranch.

They were proud of their self-sufficiency and strength. We learned that Carmelo was 80 years old. Yet he still takes care of all the work on the ranch and seems at least 15-20 years younger. They both attribute this to their healthy, ranch lifestyle. It was humbling to visit with them and get a small glimpse into their lives. Once again, we felt deep gratitude for the hospitality of the ranchers along the Baja Divide route.

Carmelo, Rosalina and their mule with PedalingGal. Rancho Riconada, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

From Rancho Riconada we had a long stretch ahead of us without access to clean water. So they generously gave us 12 liters of water from their well. With that, we would have enough water to make it to Mulegé, the next big town.

Hiding from the afternoon sun in the shade of a tree. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Another water crossing, as the valley gets narrower. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling in the floodplain. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The late afternoon light was lovely on the buttes. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Not long after leaving the ranch, as we slowly pushed our bikes across another river crossing, Carmelo passed us on his mule. He told us he was “going for a walk.” Then he waved, wished us bien viaje, as he disappeared down the road. It was clear that in this rugged country, traveling by mule was far superior to any other form of transportation we could think of.

Carmelo, “out for a walk” on his mule. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The water often looked clear, but it didn’t have much and was sometimes covered with thick mats of algae. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The cliffs drew even closer as the day progressed. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As the sun lowered toward the surrounding cliffs, we found a spot to camp down a short, sandy track. Although we hadn’t seen any other vehicles that day, to our surprise two pickups full of people passed us heading downhill while we were eating dinner. Not long after that we heard voices and a chain saw coming from the direction they had gone. We wondered if one of the vehicles had gotten stuck. We’ll never know. They did not come back our way.

Our campsite, south of San Miguel. Arroyo San Raymundo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

At bedtime our hands were still quite swollen from the bee stings - perhaps even a bit more than the night before. We hoped they would start to get better soon, since hands are rather important when riding bikes

Over the Top of Sierra San Pedro

The next day, about an hour into our ride we passed the tiny settlement of San Miguel (pop. 1). No, that is not a typo. The estimate of one person living in San Miguel is based on official Mexico statistics. And we can confirm that there was not much to see when we passed the spot on the map where San Miguel allegedly is located.

But San Miguel still held special significance for us. Carmelo and Rosalina had told us that the road would improve once we passed San Miguel. That gave us hope that we would eventually start making real progress again. And as we rode, the surface gradually became noticeably better. There still were difficult sections, including nine more water crossings (for a grand total of 25!) and many more dry riverbeds. But they became slightly shorter and less arduous.

Clouds briefly hung over the valley in the morning, as we rode on the slowly-improving road. Arroyo Santo Domingo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Palms along the river banks are a sure sign of water near the surface. Arroyo Santo Domingo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Someone thought enough of this barrel cactus to put a ring of stones around it. Arroyo Santo Domingo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A small herd of goats indicated we were approaching a ranch near San Miguel. Arroyo Santo Domingo, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We were excited about nearing the top of the pass over the Sierra San Pedro mountains. The scenery was increasingly dramatic and beautiful as we approached the summit. But unlike most of the other mountain passes we have crossed in Baja, this one did not have a well-defined peak. Instead, we spent about an hour near the ridge line, cycling over a series of five to six very steep hills. The route wound through a jumbled maze of cliffs and buttes with green mountain valleys in between. We started to wonder when we would actually begin the descent on the far side of the mountains.

Cresting one of the numerous, very steep hills at the top of the pass. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The steepest hills, both up and down, were “paved” with big stones inlaid in concrete. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

View of a ridge from near the top of the pass, with a green mountain valley below. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

This cow seemed to stand guard over her water. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling between the ridges at the top of the pass. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Heading for the final ridge. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Eventually we crested the final ridge and found ourselves careening down a 14% grade on the far side of the mountains. Some sections of the road were insanely steep, often with tight curves thrown in for good measure. We carefully eased our way down off of the ridge, trying to manage our speed without completely losing control. It was definitely an adventure. Even after the initial, rapid descent a series of smaller (but just as steep) hills kept us on our toes.

Trying to stay hydrated in the Baja afternoon sun. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But eventually the terrain became more moderate, and we started to notice some of the plants and animals along the way.

A male northern cardinal watched us pass by. We were surprised to learn that cardinals are present in southern Baja all year, even though they do not occur in the northern part of the peninsula. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We spotted a particularly tall prickly poppy. This one was taller than PedalingGal. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Periodically the canyon walls would close in on us again, making for dramatic scenery. The sign got our attention. We had been though plenty of rock falling areas without signs so this area must have been particularly bad. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Every so often the road would pitch over the top of another hill into a short, steep descent. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As if to highlight the perils of this road, we saw a wrecked truck at the bottom of a ravine. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Trees did their best to cling to the side of the cliffs. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

At one point we spooked a young burro, which ran away from us as we first approached. But before long curiosity seemed to take over. Tentatively, the burro came closer and started to follow us up a hill. When PedalingGal dismounted to push her bike, the donkey became even more fascinated and came a little bit closer. But if she stopped walking, it stopped. And if she looked back, it would halt and look away as if to say, “Nothing to see here!” When she turned around and started walking again, it would resume following at the same pace. It was adorable, and had us both laughing as PedalingGal started and stopped, with the donkey shadowing her the whole way. We finally left the burro behind when we took off down the next hill.

A young donkey followed us, apparently curious about these two strange travelers. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Descending through the valley. Sierra San Pedro, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The final two hours of cycling into Mulegé covered relatively flat terrain, but continued to present challenges. We found ourselves back in the land of deep sand and cobblestone river beds. We were tired, and considered stopping to camp before reaching town. But the two or three potential camping sites that we checked out were not very appealing. Plus, we both were eager to have a nice meal and a shower. So we pushed on through.

Crossing another rocky riverbed. Approaching Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

For the final run into town, we stayed on the main, dirt road rather than taking the backroads of the Baja Divide. Approaching Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We didn’t arrive in Mulegé until after 6pm, as the sun was sinking toward the horizon. It was a thrill to finally see the “city gate” at the entrance to town.

The “city gate” is designed to evoke a medieval city wall. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

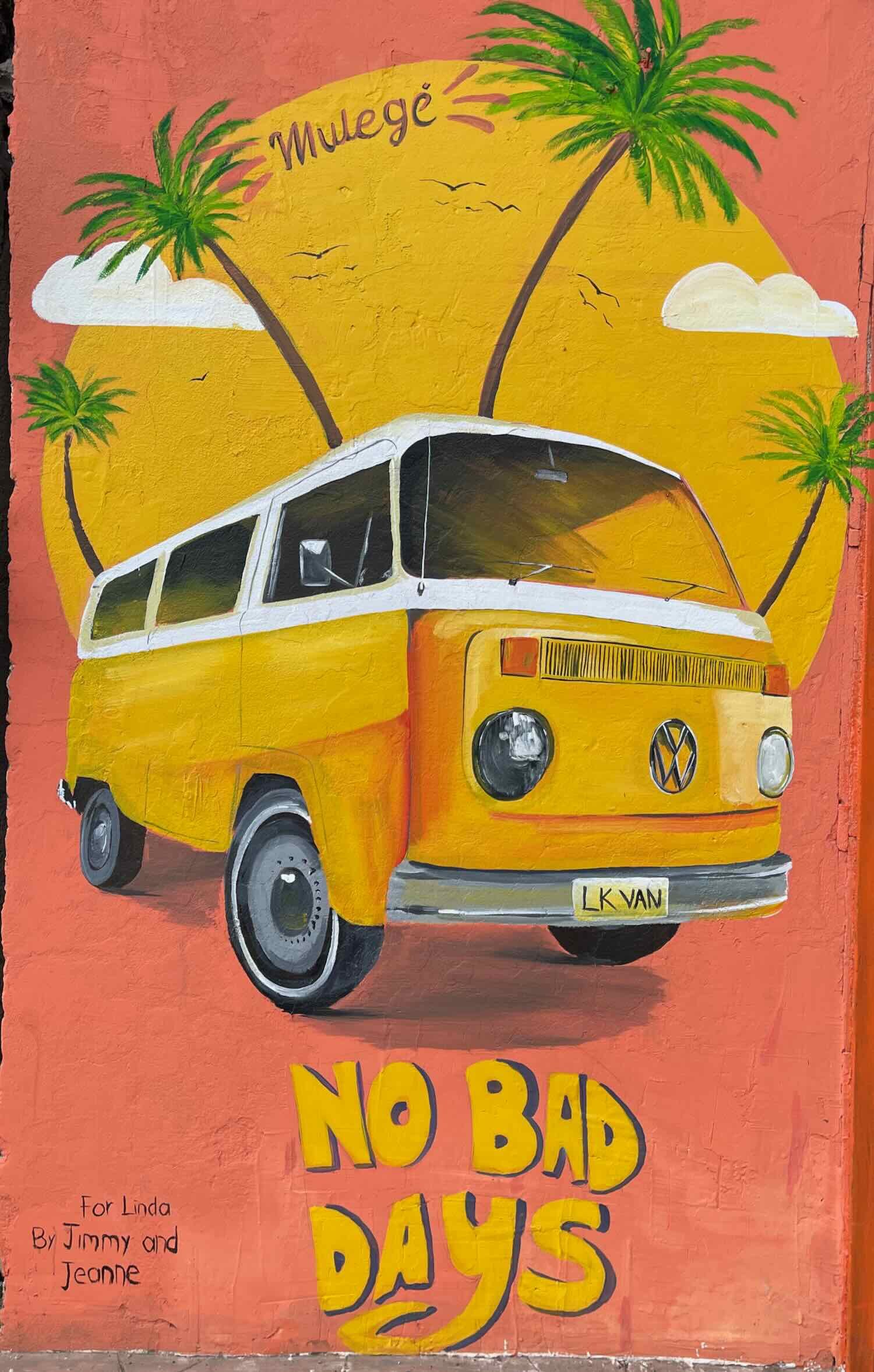

After passing through the gate, we felt like we had stepped back in time. Mulegé tries hard to maintain its historic character. It has a maze of narrow, one-way streets that lead to small, tidy plazas lined with benches. And the storefronts look pretty much like they might have 100 years ago.

One of the colorful, tranquil plazas in town. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

There are no “modern” hotels, just a handful of old-fashioned, rundown places and a couple of boutique hotels in the Centro. We went straight to the Hotel Las Casitas, one of the better run historic hotels. It’s been in business for over 50 years, before there were any roads to town and everyone arrived by boat. The rooms surrounded an intimate courtyard with burbling fountains and lots of potted plants, and were decorated with antique furniture that evoked Old Mexico. Unfortunately, the internet at the hotel was also from the last century, and was barely usable. But that seemed to be the case all over town.

A fountain in the leafy courtyard at the Hotel Las Casitas. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Festive paper decorations in the courtyard. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The Colors of Mulegé

We took a couple of days off in Mulegé to recharge, perform some repairs, and prep for the next leg of our ride. Fortunately, the swelling from our bee stings finally began to subside.

We’re still having problems with our tent zipper, so PedalingGal gave it a thorough cleaning in our hotel room. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

There also was plenty of time to go out and see some of the sights around town. The first evening we walked over to the city’s historic mission church. Built in the mid-1700s, it sits high on a hill overlooking the Mulegé River. We wandered around the grounds and admired the views from an overlook above the valley, while magnificent frigatebirds circled overhead.

The Misión de Mulegé church (1770). Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

View of the palm-lined Mulegé River, from the heights of the mission church hill. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The people of Mulegé love to display vibrantly colorful murals, fabrics, and furniture. After visiting the mission, we headed for a popular local restaurant with brightly-colored tablecloths. One of our favorite things about the restaurant was that it had a hummingbird feeder. Given that we constantly see and hear hummingbirds zipping around in the desert, we’ve been surprised that hardly anyone in Mexico has feeders. But at the restaurant we finally were able to get a good look at the two species of hummingbird that occur here, including the Xantus’s hummingbird, which occurs almost exclusively in Baja California Sur.

The next day we walked up to another prominent building on a hill - the old town jail. These days the building houses Mulegé’s history museum. Much of the information in the museum focused on the operations of the jail, which were pretty unusual. Up until 1975, when the first road was built to Mulegé, nonviolent, male prisoners were allowed to leave their cells and go to town every day. They could hold jobs and earn money to support their families, but had to return to the prison at sundown every night. The women prisoners stayed at the jail to clean and cook, but they also were paid for their labor. Without a road to escape on, the vast majority of the prisoners seemed content to follow the rules. They say that many of the families that still live in the town are descended from the prisoners who lived and worked there.

We ate our last dinner in town at a colorful taco stand lining one of the tranquil plazas. Mulegé, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But we didn’t tarry too long in Mulegé. The lack of a decent wifi connection was a challenge. Plus, now that spring was pushing the afternoon temperatures higher, we wanted to reach La Paz before the hot weather got much hotter. There would be many more mountains in our path, so it was time to roll out on the next leg of our journey.