Cycling the Guatemalan Highlands: Cuatro Caminos to Huehuetenango, Guatemala

27 October to 9 November 2023

27 Oct - Cuatro Caminos to Jacaltenango (17.1 mi, 27.5 km)

28 Oct - Jacaltenango to San Martin Chuchumatán (12.2 mi, 19.6 km)

29 Oct - San Martín Cuchumatán to Todos Santos Cuchumatán (9.8 mi, 15.8 km)

30 Oct - Layover in Todos Santos Cuchumatán

31 Oct - Todos Santos Cuchumatán to Huehuetenango (28.4 mi, 45.7 km)

1-9 Nov - Layover in Huehuetenango

The Alps of Guatemala

For a country roughly the size of the state of Tennessee, Guatemala’s landscape is strikingly diverse. The northern part of the country, which is thrust between Mexico and Belize, is mostly flat and steamy lowland jungle. But about halfway down, the land rises steeply into a tangled jumble of mountains cloaked in cold mists and inhabited by people whose indigenous traditions date back thousands of years. Many areas are decidedly challenging to reach with modern transport, giving the towns an air of mystical isolation.

Known generally as the Guatemalan Highlands or ‘Los Altos,’ this is the largest, high-altitude area in Central America. Multiple mountain ranges jumble together here, but perhaps the most storied region is the Sierra de los Cuchumatánes - the mountain range we were about to cycle into. Sparsely inhabited throughout most of history, these difficult to reach mountain valleys have been a refuge for Mayan people to escape domination by civilizations as varied as the Toltecs, Aztecs, and Spanish. These days, more tourists are finding their way into the ‘Alps of Guatemala.’ But our trip through the Guatemalan Highlands still felt decidedly off-the-beaten-path.

Wetter Than Expected

Rain had kept us hunkered down in the low-elevation town of Cuatro Caminos for the past two days. On the morning of our departure, the weather was supposed to clear up. But it turned out be just another wet day. We donned our rain jackets and headed out into the misty drizzle. Pretty quickly we were soaked.

After about a half hour of cycling we reached the foot of the Guatemalan Highlands, and our route turned sharply upwards. Over the next three days we would gain nearly 10,000 ft (3,050 m) in elevation.

Our big ascent into the Guatemalan Highlands started in this unassuming town at the foot of the mountains. As we turned onto the road toward the sierras, folks seeking shelter from the rain watched incredulously as we cycle by. Santa Ana Huista, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

From there the road pitched up onto a ridiculously steep slope that lasted for about a mile. In addition, rain had made the surface even more slick and treacherous. The road was so steep and slippery that we were barely able to push our bikes up the slope without our feet sliding out from under us. Both cars and trucks, were spinning their wheels trying to get up the mountainside. And a few vehicles had to give up completely when they began to slide out of control, backwards down the hill.

This photo does not do justice to the insanely steep incline of the hill ahead. The two cars in the photo had just slid backwards down the hill on the slick, wet road. Santa Ana Huista, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

For us, the rest of the route was an exhausting crawl up to the mountain town of Jacaltenango. Low clouds hung over the surrounding peaks, as we cycled through a mixture of fog, drizzle and rain that lasted all day. Fortunately we had anticipated the difficulty of the climb, and had planned on only covering 17 miles (27.5 km) to avoid totally shredding our legs.

The payoff came in the form of spectacular vistas across the mountains and valleys. The mist and thick tropical foliage often obscured our view. But whenever the clouds parted and we caught a glimpse of the surrounding mountains, it was gorgeous. We gained elevation so fast that the towns we passed through quickly became clusters of tiny buildings in the valleys far below us.

A breathtaking view down the Río Capulín Valley. Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Many hillsides were planted in thick groves of coffee bushes. Nearly all of the coffee plantations had some shade trees, but they were not ‘rustic’ plantations incorporated into natural forests. The shade trees included just one or a couple of species, and were trimmed to allow quite a bit of light to reach the coffee plants. Los Mangalitos, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Our destination lay just ahead in a bowl of the mountains 4,800 ft (1,465 m) above sea level. Jacaltenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We rolled into the town of Jacaltenango (pop. 22,500) a little after 2pm, soaking wet and ready to call it a day. But there was one last hurdle. The only room available in the town’s hotel was on the fourth floor! So we steeled ourselves for one last effort, to push both of our loaded bikes up six narrow flights of stairs, with tight turns on the landings between each floor. It was not exactly what we had hoped for at the end of a big ride. But we were rewarded with an expansive view of the city from an open-air patio down the hall from our room. And it was wonderful to have a place to dry off from a day that was much wetter than expected.

Our damp arrival in the mountain town of Jacaltenango. Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

From the fourth floor patio of our hotel we had a great view of the town - although the low-lying clouds often shrouded the surrounding mountains. Jacaltenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Many People in the Mountains

We were absolutely thrilled when we woke up to a sunny morning. And for the first couple of hours of cycling, we enjoyed spectacular views of steep-walled mountain valleys.

Although the landscape was extremely rugged and the roads were treacherous for cars, the hillsides were covered with a surprising density of houses, clustered tightly in bands along the lower mountain slopes. Jacaltenango itself is quite large, with 22,500 inhabitants. And there was a nearly unbroken corridor of development stretching for 6.5 miles (10.5 km) from Jacaltenango to the town of Concepción.

An unbroken band of human settlements followed our route through the rugged Guatemalan Highlands. We were impressed by the large number of people living in such a hard-to-reach place. Southeast of Jacaltenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Historians believe that prior to the arrival of the Spanish, these harsh and remote highlands were only sparsely populated. But during the colonial era and early days after independence from Spain, many native Mayan people relocated into the mountains to escape forced labor on the large haciendas that took over the fertile valleys. Even today the vast majority of mountain residents are of Mayan descent, and for many of them Spanish is not their first language.

Steeper Hills and a Little Bit of Mud

It was a good thing we had planned on another short day. The ride to San Martín consisted of an endless succession of crazily steep hills. For the first 3.5 hours we pushed our bikes as much as we rode them. It was exhausting.

Some of the steepest hills were actually within the towns. The village of Concepción had a particularly nasty hill that seemed to go on forever. Our feet slipped and slid on the wet concrete road as we struggled to gain enough traction to slowly push our bikes up into the center of town.

The village of Concepción is built right on the side of a breathtakingly steep mountain side. We just barely managed to push our bikes up into the town, because it was so hard to get traction on the slippery, wet, concrete road. Concepción, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The people of Concepción were especially friendly, and several stopped to talk with us as we took rest breaks between bouts of pushing our bikes. A guy on a motorbike with his son perched on the back and his dog sitting in front stopped to say, ‘hi.’ We learned that he had lived in the USA in the past, and that he had a sister who still lived in Florida. A few minutes later a guy in a pickup truck stopped to ask us how we were doing. His name was Felipe, and he seemed particularly pleased to see two foreigners visiting his town. We got the impression that not many people from outside the area - and especially from outside Guatemala - pass through town.

After a quick break at the top of the mountain in Concepción, we found ourselves cycling on a dirt road for the rest of the day. On the bright side, the ride into the town of San Martín was mostly downhill. But just like the uphills, the descent was brutally steep. Our brakes got a good workout - as did our hands from squeezing the brakes.

Descending towards the town of San Martín. Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

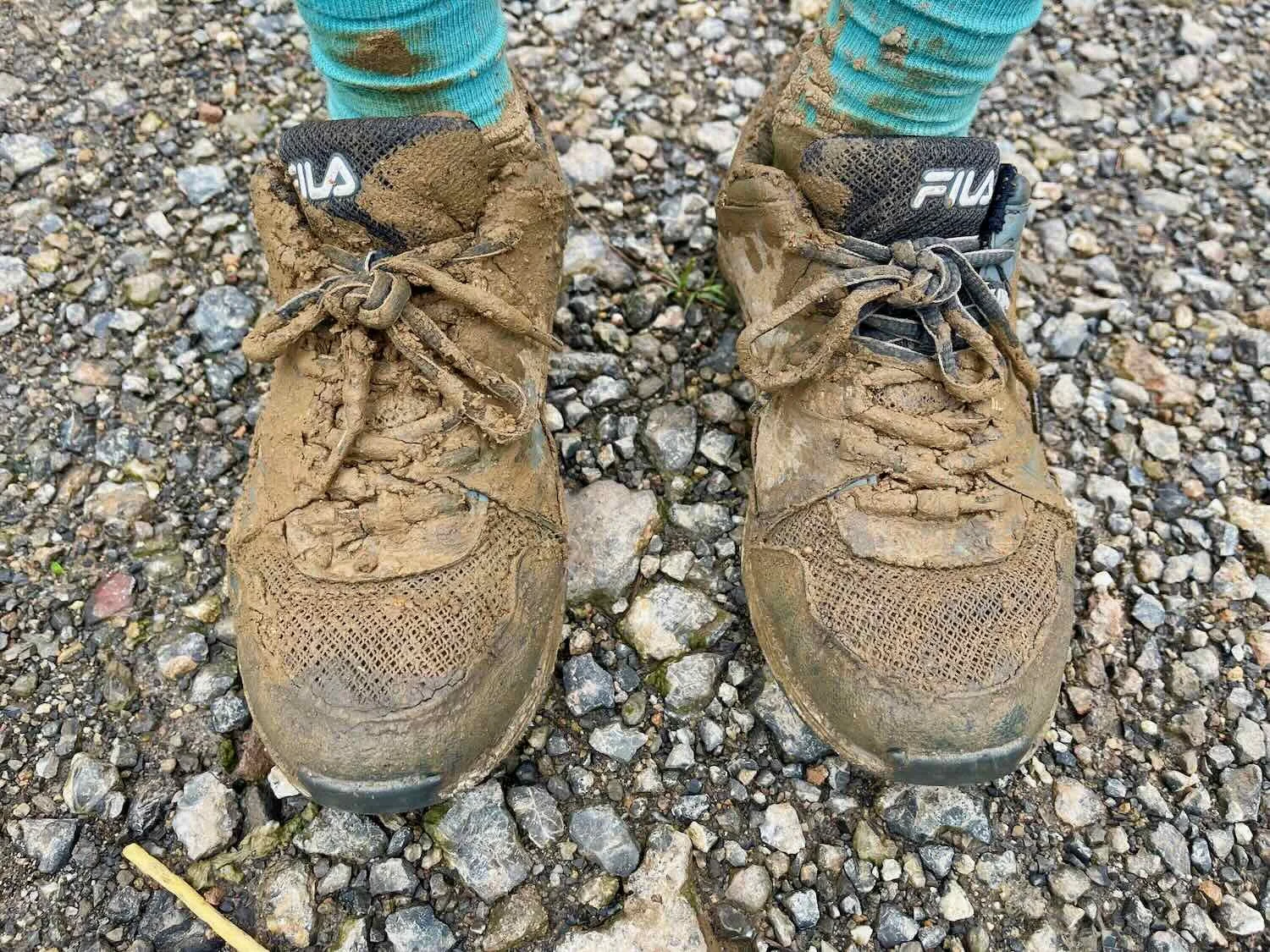

Part way down the hill we reached a section of the dirt road that was under construction. And to top it off, it began to rain. We passed several groups of heavy trucks laying new gravel. Meanwhile, the dirt road became liquified - like cycling through deep, moist, peanut butter. We got completely soaked, while our bikes and shoes acquired a muddy, brown coating.

The dirt road got rutted and muddy as we entered a construction zone. This photo was taken just before it started to rain. North of San Martín Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins

It was still raining as we arrived in town. So we were absolutely thrilled to discover that our hotel’s parking area was covered by a high corrugated metal roof. It was deeply satisfying just to ride our bikes into the parking area and be out of the rain. The enclosed courtyard also provided a calm, safe place to stow our bikes while we secured a room. Surprisingly, the ladies who ran the hotel didn’t seem to care how dirty we were. Perhaps they were used to lots of mud given all the dirt roads leading to town. Whatever the reason, they were not in the least concerned that we wanted to take our dirty bikes up a flight of stairs and into our hotel room.

The parking area of our hotel was covered by a high, corrugated metal roof. That was perfect for us, since a light rain was falling when we arrived. The machine in the bottom left is for grinding corn. The corn in these mountain communities is planted by hand, harvested by hand and shucked by hand. They then use a grinder to make cornmeal for tortillas. San Martín Cuchumatan, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Not long after we settled into our room the rain started coming down hard. We could hear it pounding on the big metal roof. It was soooo nice to be warm, and relatively dry.

There were only a couple of dinner options in town. We ended up at a rustic, open-air diner. The restaurant was adjacent to the town’s small, dirt plaza and modest church. However, the scene was anything but tranquil. Our meal was punctuated every few minutes by explosions so loud that they sounded like someone was firing a cannon next door.

In fact, it was just a teenage girl setting off really enormous explosions (think, an 8-inch stick of dynamite) inside a metal canister in the plaza. That was our first introduction to bombas - the bomb-like fireworks that sound like a canon, and that are very popular in Guatemala. Locals would later tell us that folks will explode bombas to celebrate just about anything, including birthdays, holidays, anniversaries, graduations… or just because they like the eardrum-shattering, window-rattling bang. These explosions have been known to set off car alarms a block away, not to mention waking up sleeping cyclists. During celebrations it can feel like you are in a war zone.

Our dinner spot in San Martín. The meal was accompanied by the sound of periodic cannon-fire (bombas) from the small plaza next door. San Martín Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Even Steeper Hills and A Whole Lot of Mud

The next day, by the time we were ready to hit the road, the rain had subsided into a light drizzle. We cycled out of San Martín into the mist.

Much to our chagrin, our route stayed on dirt roads for the entire day. As a result, we slogged through every type of mud imaginable, from slushy gravel to ankle-deep sludge. Pretty soon we were about as dirty as we had ever been while out on our bikes.

Enjoying a day of playing in the mud. Southeast of San Martín Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Rivulets of chocolate-colored water streamed across the muddy road, splashing up on us and our bikes. Southeast of San Martín Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

And then there were the hills. As if they weren’t challenging enough, we managed to add another layer of difficulty to our day’s ride.

About 2.5 hours after departing we reached a sign across our route announcing that the road was closed for construction. It had an arrow pointing down another road, which was supposed to be the detour. We could see the other road on our map, and it looked like it was about the same length to our destination as the original route. But we had no other information about it, so we weren’t sure what to do.

On the one hand, it’s often easier for bikes to get through a construction zone than cars - we could weave around the construction vehicles if needed. So we might have been able to muddle through. Unlike in the United States, construction zones in Guatemala were usually not completely closed to bike traffic. But on the other hand, with the rain and soggy road surface, we could have found ourselves mired in some pretty bad muck if the heavy machinery had torn up the gravel surface - and if it was bad enough, we might not actually be able to even push our bikes through. But, of course, we had no idea what to expect on the detour, either.

As we stood in the mud puzzling about what to do, a local man came up to us to offer his advice. He felt pretty strongly that we should take the detour. He said that the construction crew would be working with heavy equipment on the road, even though it was a Sunday and it was raining. He told us that the detour had some more hills, but he thought it was still the better option.

So we took his advice, and headed down the detour. But really, we should have known better. One lesson we have learned repeatedly is that advice from locals can be invaluable, except when it comes appreciating what it is like to travel by bike. Distances are usually misjudged, and difficult terrain is always underestimated.

The detour was brutal, including several hours of climbing and descending. It plunged down into two very deep, very steep-sided, V-shaped valleys. The descents were slippery and treacherous - causing us to grip our brakes tightly all the way down to avoid gaining any speed which might send us sliding off the road. And the climbs out of the valleys were impossibly steep. On the final ascent, PedalingGal was barely able to push her bike 20-30 feet (6-9 meters) at a time before having to stop and rest. It felt like a miracle when we finally reached the edge of town in Todos Santos Cuchumatán.

Hike-a-bike up one of the steep, sloshy hills. Aldea Chicoy, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we entered town we reached a road paved with concrete. It was heaven. There was still one more, ridiculously big hill to get to the center of town where our hotel was located, but at least it wouldn’t be so muddy.

We had arrived in the midst of the town’s two-week, annual Heritage Fair which culminates on November 1 with a famous, raucous, horse ‘race’ that is more like an extended version of Pamplona’s running of the bulls than what most people think of when they hear the term ‘horse race’ (more about that later). The road was lined with market stalls selling food, clothing, gifts, pastries and sweets, and even a few carnival games. In spite of the damp weather, the streets were crowded with people out for an afternoon stroll, socializing, or shopping for the holiday.

A banner welcomed us to the town’s annual Heritage Fair which lasts for two full weeks at the end of October and beginning of November. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we had feared, the first hotel we visited in town was completely booked. The Heritage Fair is probably their busiest two-week stretch of the entire year. So we considered ourselves very lucky when the second hotel actually had room for us, even though it was very basic. The rooms were tiny, with hardly any space to move around the beds. There was no way we were going to get two bikes into one of those rooms. To get everything safely inside we ended up renting two rooms (at appx US$14 each) and even then it was a very tight squeeze. In PedalingGuy’s room, he literally had to step over the front wheel of his bike to get into the bathroom. To top it off, the rooms were very cold and damp (at an altitude of 8,200 ft), and there was no hot water - only ice-cold water in the shower. But under the circumstances, we were happy not to be sleeping out on the street.

Before we could bring the bikes up to the room, though, we really needed to clean them off. The teenage girls running the hotel told us there weren’t any car washes nearby. But that seemed unlikely, given the preponderance of dirt roads just outside of town. So we asked a guy passing by on the street and he confidently told us that yes, there was a car washing hose at a gas station not too far away.

To our chagrin, it was at the bottom of a very steep hill. And when we arrived there was a bit of confusion about whether we had to pay (no), and whether we could wash our own bikes or someone else would have to do it for us (we just went ahead and grabbed the hose and sprayed down our bikes, hoping no one would object). There were several cars also waiting to get washed. And at one point an older man got into a loud argument with a younger guy who was spraying off one of the waiting cars, and even kicked the younger guy. It was pretty tense, especially since we didn’t really understand what they were fighting about (they were arguing in Mam, the local, indigenous language). But fortunately, neither one of them seemed interested in us.

Our bikes were so encrusted with mud that we actually had to get hold of the hose twice, because our first, hurried attempt to clean the bikes didn’t get quite enough of the dirt off. When we were finally done, we trudged our bikes back up the steep hill to the hotel.

The Todos Santos Heritage Fair

With a population of over 33,000 people, Todos Santos Cuchumatán is one of the biggest towns in Guatemala where longstanding Mayan traditions are still observed. The primary language of most residents is Mam (a Mayan dialect). And a very high proportion of people in the town wear traditional highland garments year around - woven skirts and embroidered blouses for the women; striped pants and shirts with embroidered collars for the men.

When we returned after dinner, we found that the festivities had enveloped our hotel. There was a marimba set up in the garage, with a team of three musicians banging out a lively tune. Out in the street, a group of clearly drunk men were dancing to the marimba music. Their dance moves consisted of low-key shuffling up and down the street, shifting their weight back and forth and rhythmically rocking their arms and shoulders in very restrained movements. Beer cans littered the ground. And a small crowd of also-drunk onlookers shouted occasional words of encouragement.

A marimba band played lively tunes, sheltered from the rain in the garage of our hotel. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Men in traditional dress danced rhythmically to the music, shuffling back and forth while consuming lots and lots of beer. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As with many festivals around the world, getting totally plastered is part of the tradition - both as a form of entertainment and as a means of reaching a euphoric state that has a religious dimension. For the men of Todos Santos it’s a particularly unusual experience because drinking alcohol is strictly banned throughout the rest of the year.

One of the biggest events of the Heritage Fair is the annual Race of Souls - the horse ‘race’ mentioned above - which would take place in three days. There were signs celebrating the race posted all over town, and we were told that it is probably the single most important event of the year in Todos Santos Cuchumatán. People from all over the world come to witness the spectacle.

In a nutshell, the men of the town spend the 24 hours before the race drinking and dancing to enter a trance-like state (and to lower their tolerance for risk taking). Then, dressed in colorful costumes of ribbons and feathers, they mount rented horses, which they ride at breakneck speed up and down a dirt track at the edge of town from 8am to around 4pm. The race is not won by timing, or beating the other competitors to a finish line. Rather, the winner is chosen from among the participants by the other men of the town based on their displays of endurance and skill (e.g., staying on your horse), and bravery (e.g., getting back on your horse after falling off, riding with no hands, and other displays of courage).

The Race of Souls has been held annually in Todos Santos Cuchumatán for at least three centuries (quite possibly even longer). Participation is considered a rite of passage for the men of the region, and they are expected to enter in at least four races during their lifetime. Most of the men only ride a horse (and drink alcohol) once a year during the Heritage Fair. As a result, the race is full of mayhem and danger. The main goal of most participants is just to stay on their horse as long as possible. Many riders fall off their horses and are seriously injured. Occasionally someone dies. Death of a participant in the Race of Souls is considered a sacrifice that will bring good fortune to the community in the future.

Image from a promotional poster for the Race of Souls, an annual test of bravery that is steeped in tradition. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala.

But we would not be staying long enough to be spectators at the race (the hotel was fully booked and we couldn’t find any place to stay). Instead, we spent an evening and the next day soaking up the sights and sounds of the less infamous aspects of the Heritage Fair. On the first evening, the main event hall in town was packed with spectators for a local talent show. Groups of kids performed costumed dances and sang songs, both modern and traditional, while family and friends cheered them on.

This group of teenage boys performed a dance in traditional costumes, and wielding machetes. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The large, community auditorium was full of friends and family there to cheer for their favorite acts. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Colorful banners were hung in the central church to celebrate the holiday. Every so often, guys in the town plaza exploded the big bombas fireworks that sounded like cannon fire. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The town’s streets were relatively quiet the first evening, probably due to the soggy weather. But the festival vendors were still open, hoping that a few more people would stop by. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Early the next morning we went for a walk. On a small lot near the center of town they had erected a mini fairway, with carnival rides. A crew of men was hard at work checking and tightening every single one of the bolts holding the Ferris wheel together.

Low clouds formed a mist around the Ferris wheel that was set up on a small lot in town. The town was at a high enough elevation that we were either in the clouds or the clouds were just overhead most of the time. It was impossible to dry clothing or anything else. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Three guys could be seen among the metal beams of the Ferris wheel, tightening all the bolts to get ready for another day at the fair. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Down along the main road through town we came across the start of a foot race. The first group to run was the under-14 age class. When we arrived they were still getting their instructions and lining up for the start.

Kids aged 14 and under gathered around the announcer to get their instructions for running a race during the annual Heritage Fair. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

It took them quite a while to get the race under way. The officials had a heck of a time clearing the road that the kids were supposed to run down. It went straight through the main market area, where vendors had set up dozens of temporary stalls right in the middle of the road. Everything had to be moved to the sides. And even then it was a losing battle to try to get the pedestrians to stay out of the way. Finally, after at least a half hour of road clearing, the runners took off. The kids ran incredibly fast as they sprinted down the hill, indicative of kids who don’t run races very often.

The under-14 age group finally took off running, racing down the hill as fast as they could. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Before long the kids came running back down the road in the opposite direction, heading for the finish line. We stood by the side of the road, applauding and cheering for the kids in the lead as they ran by. That really made us stand out as foreigners. None of the other spectators from the town clapped, let alone cheered. The locals were culturally very reserved. But the kids seemed to love the attention. Nearly all of them gave us a big, proud, smile or a thumbs up when they heard us cheering. One little girl even called out “Gracias!” as she ran by.

It didn’t take long for the crowds of vendors and pedestrians to close in behind the race, filling the street with colorful merchandise for sale.

The main road through town became a colorful jumble of vendors and shoppers in town to celebrate the Heritage Fair. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The traditional clothes worn by many people were all hand woven, and individually tailored. So a whole industry related to the making of clothes flourished in the town. There were numerous shops selling uncut bolts of cloth in the traditional patterns, plus a wide variety of colorfully embroidered accessories to give each outfit a bit of personal flair. Mixed in among the traditional shops were plenty of others selling more modern clothing, toys and household goods.

One of the many shops selling bolts of woven cloth used by the Mam Mayans to make their traditional clothing. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

No fair is complete without vendors selling all kinds of sweets. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A Guatemalan Icon - The Chicken Bus

One of the most iconic sights in Central America is a form of transportation known affectionately as the ‘chicken bus.’ And Todos Santos Cuchumatán had its share of these beasts rumbling along the narrow streets of town. They are second-hand school busses from the USA that have been repurposed as public buses for the masses, and are the primary form of public transportation in much of Guatemala. Buses are privately owned and operated by individuals, who raise the money to buy a bus and start their own bus route.

Flamboyant decorations give each bus its own, unique identity. And in Guatemala, the chicken buses have reached their highest form of artistry. They are almost always painted in outlandishly colorful patterns, often with cartoon characters on the back panel, and religious phrases inscribed just about anywhere. Some even sport a dazzling array of flashing lights and/or musical horns. They’re called chicken buses because you can take almost anything on them, including live farm animals like chickens. Bulky items are lashed with ropes on top of the bus, where you will often see someone arranging things while the bus drives down the road. Local farmers will even take their crops to town loaded in big bags, stacked on the top of the buses.

A fine example of a gloriously-painted ‘chicken bus’ on its way through town. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Unfortunately, one other thing that all chicken buses have in common is that they belch extraordinary amounts of toxic-looking, black exhaust. We began to wonder why the same buses that are smoke free in the USA produce so much dark exhaust once they are imported to Guatemala. Do the new Guatemalan bus owners remove some of the pollution technology on the buses to get better gas mileage? More likely, it’s just that the buses are using high sulfur diesel fuel that is unavailable in the USA, and which probably requires engine retuning. There didn’t seem to be a single chicken bus in the whole country that did not emit big, black clouds of smoke - especially when laboring up a big hill in front of a cyclist struggling to get up the same hill.

A Guatemalan chicken bus let out a cloud of toxic-looking, black smoke as it accelerated after making a turn. This amount of noxious exhaust was pretty typical for a chicken bus. Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The other universal characteristic of chicken buses is that they torpedo down the road with the velocity of a runaway train. They are loud and brash, honking their horns frequently to get the attention of potential customers, and speeding along at a pace that allows the driver to barely keep control (or so it seems). If you are on a bicycle, you don’t mess around with chicken buses. Luckily, with all the horn blowing and loud engines you usually hear them coming and can get out of the way. If the space the bus has to pass you is barely enough, they will blow their horn but they won’t slow down. It’s always best to yield to the chicken buses.

Just a stone’s throw from the bustling center of town, signs of the more rural lifestyle common in the Guatemalan Highlands could be seen on the back streets. Farm animals - especially chickens and turkeys - wandered in people’s yards. The style of the buildings, and their decorations, became more rustic.

As we walked back to our hotel, we heard a college-aged guy in traditional dress speaking perfect English. We asked where he was from, and he said Oakland, California. He told us that he had returned for the festival, and that the merrymaking would last most of the month of November. His father was apparently a rather important person in town, and he said his family would be hosting some big parties. We later learned that upwards of 5,000 people originally from Todos Santos now live in Oakland, California and that it is one of the biggest migration destinations for people from this area.

A Beautiful Day for a Bike Ride

The next morning we rode out of Todos Santos Cuchmatán into a beautiful, brisk morning. The air was cold, with a bit of mist, and the sky was full of dramatic clouds. But the rain and drizzle had finally ended. And the chill in the air was welcome as we cycled towards the highest elevation yet on our current trip. It was a wonderful feeling to be cycling without rain.

A magical sunrise over the Sierra Cuchumatanes. Leaving Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We gained elevation rapidly, and before long we were high above the town where we had spent the past couple of days. View back towards Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Along the road we passed a chicken bus unloading bundles of fire wood from the rear luggage compartment. One of the bundles split open and spilled all over the road as it was being jettisoned from the bus. The buses cram a whole lot of baggage in the back. But there’s often too much to fit inside, so the overflow gets strapped on top. East of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

On a steep part of the road where we had stopped to rest we met Julian, who was walking the other way with his two young sons. We quickly learned that Julian had lived in several towns in the USA, mostly working in agricultural fields. His sister still lived there, and he said he hoped to go back someday.

Our new acquaintances, Julian, and his sons Daniel and Franctonio. They are dressed in the traditional clothing for men. Todos Santos is one of the few large towns in Guatemala where men still wear traditional clothing year round. Traditional clothing for women is much more commonly worn, even in bigger cities. East of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The views of the mountains as we gained elevation were spectacular. Sierra Cuchumatanes, East of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A very popular design element on houses in rural Guatemala is a porch or terrace that has a railing supported by concrete columns. They’re often ornate, sometimes even taking the shape of a swan or a seahorse. Along the way to Huehuetenango, we finally found the source of these columns - with a display of the various sizes and designs available for purchase lining the road. East of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Within a few minutes after leaving Todos Santos, and for the next couple of hours, we were passed by at least 23 trucks heading down the mountainside carrying loads of 4-6 horses each, plus as many as 10 guys riding on top. Somehow the men avoided falling off as the trucks swerved down the tight hairpin turns on the mountain road.

They were almost certainly heading to Todos Santos to offer their horses for rent to the participants in the Race of Souls. We had heard that very few people in the mountains own horses, so they have to be shipped in from the lowlands for the race. It can be very expensive for the riders, who save up all year to be able to participate in the keynote event of the festival. There had to be well over 100 horses being transported into the small town. We had a hard time imagining where they would put all those horses, let alone accommodate all the additional people that came along with them.

One of 23 trucks heading towards Todos Santo to make some money renting horses to the riders in the Race of Souls. The trucks had 4-6 horses inside, and as many as 10 guys riding on top. East of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

As we rode higher and higher into the sky, clouds would periodically envelop the road. At times we were above the clouds, looking down on them as they filled the steep-sided valleys. Small birds darted among the bushes, and fed on the nectar of brightly-colored flowers.

Many sections of the road were too steep to ride, and we pushed our bikes uphill for many miles. Sierra Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One regal tree stood out among the others, on the far side of a steep-sided valley. Sierra Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A rustic farm building in the Guatemalan Highlands. Sierra Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Remittance Mansions

In the small communities that lined our route into the mountains, we saw many houses that had American flags painted on them. Most were relatively small designs, often on the corners of decorative trim near the roofline that included other images like flowers and stars. But some of them were big, bold flags that covered a large portion of an exterior wall.

This fine-looking, spacious home on a remote mountain road in Guatemala sported United States flags painted near the roofline. The flags were probably an indication that the home owner had lived, and earned the money to build the house, in the USA. La Ventoza, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

We later learned that these homes are known locally as ‘remittance mansions,’ built with money sent back to Guatemala by relatives who emigrated to the USA. They say that as many as 30% of the people who call Todos Santos Cuchumatán home live most of the year in the USA. The owners incorporate US flags on their homes as a way to show gratitude for the opportunities they gained while in America. Sometimes the whole family has moved to the USA, and the Guatemalan properties sit empty much of the year - or may never even be lived in if the owners don’t return. (If the owners are in the USA illegally, the home may also serve as an ‘insurance policy’ - a place to return to if they end up being deported - or a tangible asset that can later be sold when cash is needed.) The flags on these homes were just one more reminder of the extensive connections between the USA and rural Guatemala.

Over the Top and Into the City

We finally made it to the top of the ridge after more than five hours of cycling. The road topped out at more than 11,100 ft (3,400 m) - the highest elevation we had achieved since leaving Deadhorse, Alaska more than a year ago. At the top we rode through an area of decidedly strange vegetation that hugged a small area along the crest of the ridge. A tree with silvery leaves, and a huge agave with densely packed clusters of dark, yellowish-green flowers, were plants that we’d never seen anywhere else.

The huge and robust Agave hurteri has no common name. It is only known from five, small, mountain tops, mostly in Guatemala - and one of which we rode across on our way to the city of Huehuetenango. Sierra Cuchumatanes, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A quick descent off of the cold, damp ridge dropped us onto a high plateau of rolling hills blanketed with farmland. One of the things we noticed right away was the prevalence of livestock. We saw more sheep, pigs, horses and cows in a few miles than we had seen in all the rest of Guatemala so far. It was pretty clear that this was where all the horses that were headed for Todos Santos had probably come from.

Many of the pigs, sheep and cows that we saw on the high plateau were not kept in pens, but had a rope tied around their necks that was just short enough to keep them from wandering out into the road. Paquix, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

An hour later we plunged over the edge of an escarpment, and flew down a very long, very steep descent into the city of Huehuetenango (a.k.a., Huehue). The road was full of potholes, and it was super narrow, so we really had to keep our wits about us on the way down. We dropped a stunning 3,500 ft (1,060 m) in just under half an hour - and that included several stops by the side of the road to let our squealing-hot brake rotors cool off. Fortunately, the road’s tight hairpin turns kept the vehicle traffic from going too fast. With an average speed close to 25 mph, we were able to keep pace with the traffic most of the way down. But we were quite relieved when the slope finally moderated as we rolled into the city.

It was 31 October - the afternoon before All Souls Day (as the Day of the Dead is more commonly called in Guatemala). And everyone seemed to be out and about completing last-minute chores before the big holiday. Several miles outside the city center we hit a huge traffic jam of folks trying to make their way into the city. The cars on the road were literally at a standstill, going nowhere. There was no accident, just too many cars trying to enter the city at once. Drivers didn’t pay any attention to road crossings where there were no traffic lights, so every intersection was clogged, bringing traffic to a halt.

Fortunately for us, there was usually just enough space for a couple of bicycles to squeeze through. In typical Guatemalan style, we weaved our way back and forth among the stopped or slowly moving cars and trucks, often accompanied by a small fleet of motorbikes. It was pretty stressful, but at least we were making forward progress - unlike the vast majority of the cars. The snarled traffic extended all the way into the very heart of the city. We later discovered the primary source of the backup was that the street our hotel was on had been repurposed for selling flowers for All Souls Day. It was worse than a Christmas sale, because everyone was out buying or selling flowers all at the same time.

Celebrating All Souls Day

After settling in to our hotel we went for an All Souls Eve walk. A light but steady rain had moved in, causing most of the folks out on the street to hustle along on their business without lingering. The road next to our hotel was packed full of flower vendors working hard to make a last-minute sale to people who would take the decorative bouquets to their departed loved ones in the cemetery tomorrow. We even spotted a few businesses that were decorated for Halloween, even though it’s not a traditional Guatemalan holiday.

Bushels of flowers in a temporary flower market provided splashes of color along the street where our hotel was located. Shoppers were buying bouquets to take to the cemetery, to decorate their ancestors’ graves for All Souls Day. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Halloween is not a traditional holiday in Guatemala. But since many folks have spent time living in the USA, the holiday has slowly gained popularity here. It’s basically seen as a chance to have fun costume parties, and to enjoy another day of festivities. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The next day, 1 November, was the big holiday. In the central plaza, facing the city’s main municipal building, we passed a large altar decked out in ribbons and flowers that was dedicated to some of the city’s deceased forefathers.

An alter dedicated to the memory of some of the city’s forefathers had been set up in the central plaza. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But the main action was over at the municipal cemetery. There, families gathered around the graves of their ancestors to remember them and pay their respects. Tombstones were washed clean, and adorned with brightly colored ribbons and flowers. In fact, many of the graves were designed to include special concrete containers for flowers, and hooks for hanging wreaths, ribbons, and other decorations. Some folks also left offerings for their deceased relatives, including their favorite foods and beverages. A mariachi band played ballads while strolling among the tombs. And outside the cemetery gates, a fair consisting of food vendors, gift shops, and even a few carnival rides for the kids added to the festive atmosphere.

Colorful flowers and ribbons decorated most of the graves, giving families a chance to celebrate the memories of their deceased relatives. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A mariachi band played ballads among the graves at the municipal cemetery to celebrate All Souls Day. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

On the street outside the municipal cemetery, a small carnival with rides and games provided entertainment for families with children. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Waiting Out the Rain in Huehue

We spent the next six, soggy days in Huehue waiting for a wet weather system to pass. The rainy season in Central America lasts a bit longer than it does in Mexico - often through the middle of November. So although we had hoped that the damp weather would begin to subside by early November, it wasn’t a complete surprise that tropical storms continued to swirl in both the Caribbean and Pacific Oceans - dropping more moisture on Guatemala. At least Huehue was an enjoyable place to hang out while we waited for the weather to clear.

Although it was very rainy, we were thrilled to discover that our gear was able to dry out in our hotel room - even without air conditioning. Pretty much everything we owned - including gear we hadn’t even used - had become thoroughly damp during a week of cycling through montane cloud forests. The air had been so full of moisture that nothing escaped its touch. We really enjoyed being dry again.

Each day we made a point to get out and walk around the city. Huehue is not a tourist town, but it still had interesting places to visit. The big, central plaza had some unique touches, like a bougainvillea-covered, circular bench in the middle (where you’d usually find a gazebo), and a 3-dimensional, fiberglass rendition of the province with various peaks and towns marked by little flags. Of course, there’s also an elegant cathedral and a bustling city market.

The glistening white, neoclassical facade of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception rose gracefully on one side of the central plaza. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The inside of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was just as clean and refined as the outside. Built in the mid-1800s, it’s a lot newer than many of the others cathedrals we’ve seen. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Instead of a gazebo, the central element in Huehue’s main plaza is a circular bench under a bountiful canopy of bougainvilleas. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

On one side of the plaza there was a 3-D, fiberglass replica of the department of Huehuetenango. We had fun tracing our route over the Guatemalan Highlands on the big map. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The walkways through Huehue’s municipal market were particularly narrow, making it hard to squeeze past other shoppers and giving the market a crowded feel. Vendors hung their products densely on racks that stretched high towards the ceiling. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One restaurant where we ate was decorated with colorful bundles of dipped-wax candles hanging from the ceiling. We wondered if the building had been an old candle factory. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

One morning we walked out to see one of Huehue’s more eccentric attractions, the Temple of Minerva. Built in the earliest years of the 20th century, the monument was part of a vigorous campaign by Manuel Estrada Cabrera, the country’s dictator at that time. His vision was to promote scholarship and education by holding annual Festivals of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, commerce and strategy. More than 20 Temples of Minerva were built in cities around the country to serve as focal points for the fiestas, which involved student competitions and the awarding of national prizes to the best student scholars. But in 1920 Estrada Cabrera was forcibly removed from power, declared mentally unsound, and jailed for the rest of his life. And that was the end of the Festivals of Minerva. Of the 20 original temples, only five remain. And one of them is in Huehuetenango.

A bit of Greek culture in Guatemala - the Temple of Minerva was built as part of a national movement at the beginning of the 20th century to promote education and scholarship. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A mural near the Temple of Minerva depicted three of Guatemala’s most iconic symbols: a resplendent quetzal (the national bird), a marimba (the national musical instrument), and Tecun Uman (the national hero who legend says was killed by the Spanish in a decisive battle with the highland Mayas in 1524). City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

The streets and sidewalks in central Huehue were very narrow, probably dating back to the time when horses and carriages were the primary form of transportation. In addition, the sidewalks were often overtaken by street vendors, who thought nothing of setting up their canopies and food carts safely out of the traffic - and forcing pedestrians to walk in the road. As a result, there was a constant jostling of people, motorbikes, cars and trucks for road space.

So you would think that Huehue would be the kind of city where tuk-tuks - those small, nimble, mini-taxis - would prevail. But no, there weren’t any tuk-tuks. The narrow, crowded streets were overrun by chicken buses - the most oversized, lumbering, and hard-to-maneuver vehicles imaginable. The buses would crawl slowly through the tight gauntlet of vendors, pedestrians, motorbikes and cars blaring their horns in a mostly-futile attempt to clear a path. As a result we had plenty of close encounters with these dazzlingly-painted behemoths. Here are a few photos that give a feel for the showmanship embodied in the chicken bus:

Finally, after about a week of rain, the sun finally emerged. We were glad we stayed an extra day, because the city was completely transformed. We had come to think of Huehue as a pleasant, but rather subdued town. But that was wrong. Under fair skies, everyone seemed to emerge from their homes to soak up the sunshine. We got the impression that all the inhabitants had been suffering from cabin fever, and couldn’t wait to spend some time outside after the rain stopped. It was fun to see all the people hanging out in the main plaza and just strolling the streets. The city felt much more vibrant and alive.

The tower of the departmental capital building glowed against the clear, blue sky. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

A fair-weather sunset over the city’s municipal building on the main plaza. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

Trouble with a Wheel

We had planned to leave Huehue on 9 November, now that the rains had stopped. But as we were getting ready to leave, PedalingGuy noticed some cracks that had formed in the rim of his back wheel, around the points where the spokes were attached. A quick bit of research led us to the conclusion that this was not good at all, and that the rim was likely to fail and be unrideable in the not too distant future.

We were stopped in our tracks when PedalingGuy noticed that cracks had formed in the rim of his back wheel, near five of the spokes. This definitely seemed like something we should to get fixed soon. City of Huehuetenango, Dept of Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Copyright © 2019-2023 Pedals and Puffins.

But we couldn’t simply order a new, prebuilt wheel, because our bikes have Rohloff Speedhubs (which have the gears inside the hub). As a result, a new wheel would have to be built around the existing hub. This required finding someone who had the parts and expertise to build a wheel from scratch, accounting for details particular to the Rohloff.

After talking to a local bike mechanic in Huehue, as well as a couple bike mechanics in Guatemala City, we learned a few things. The first was that the mechanics had never even seen a rim the size that we needed (45 mm wide) anywhere in Guatemala. We would have to order one from the USA, which would take at least 2-3 weeks (provided there were no holdups in customs). Second, we would have to find someone locally who could rebuild the wheel, despite the fact no one had experience building wheels with Rohloff hubs.

Our best bet for finding a good wheel builder seemed to be in Guatemala City. Plus, if we had the new rim shipped there, it could be in transit while we completed the nine days of cycling that lay between us and Guatemala City - saving us us some waiting around time.

We then had to decide if we felt lucky (yes, just like in the Clint Eastwood movie). Would the cracked rim survive the nine riding days to Guatemala City, or would it leave us stranded along the way? Even more important, was it safe to ride? The bike mechanic we visited in Huehue seemed to think we had a good chance of making it to Guatemala City, so we decided that we felt lucky.

We then spent a whole day figuring out things like:

Amazon does not ship to Guatemala

the Guatemala City bike shop couldn’t order the rim for us, because their online system would not accept our foreign credit card

unless you use a reshipper with bulk rates, shipping a 3 pound package from the USA to Guatemala can cost more than a plane ticket home

depending on who you ask, Guatemala may or may not have a postal service (it has gone out of business a couple times which creates confusion)

whether or not the Guatemala Postal Service exists, no one seems to recommend using it

FedEx and DHL seem to be the best bets for mail, and

customs can often be a challenge, but this is usually solved by paying an uncomfortable amount of tax in a timely manner

We then placed our order for a new 45mm rim, some rim tape, and tire sealant along with some shipping magic from DHL.

The following day, after calling on all available good karma from the past (and sage advice from an 18 year old bike mechanic), we decided to hit the road and try to make it to Guatemala City with the cracked rim, in time to receive our package from DHL. To hedge his bets, PedalingGuy did redistribute some weight from the back of the bike to the front, and made a point to under inflate the back tire a little to relieve some of the pressure on the cracked rim.

Our next big stop on the way to Guatemala City would be Lake Atitlán, the the deepest lake in Central America, in a valley ringed by volcanoes.