Cycling Over the Cascades: Libby, Montana to Sedro-Woolley, Washington

1 - 14 October 2022

1 October - Libby to Noxon, MT (55.7 mi, 89.6 km)

2 October - Noxon, MT to Sandpoint, ID (42.5 mi, 68.4 km)

3 October - Sandpoint, ID to Usk, WA (53.0 mi, 85.3 km)

4 October - Usk to Gillette Lake, WA (53.0 mi, 85.3 km)

5 October - Gillette Lake to Colville National Forest, WA (47.5 mi, 76.4 km)

6 October - Colville National Forest to Republic, WA (33.5 mi, 53.9 km)

7 October - Layover in Republic, WA

8 October - Republic to Tonasket, WA (40.7 mi, 65.5 km)

9 October - Tonasket to Okanogan, WA (38.3 mi, 61.6 km)

10 October - Okanogan to Winthrop, WA (32.5 mi, 52.3 km)

11 October - Winthrop to Okanogan National Forest, WA (27.0 mi, 43.5 km)

12 October - Okanogan National Forest to Marblemount, WA (62.7 mi, 100.9 km)

13 October - Marblemount to Sedro-Woolley, WA (43.6 mi, 70.2 km)

14 October - Layover day in Sedro-Woolley, WA

Staying a Step Ahead of Winter

There was definitely a nip in the air. Nighttime temperatures were now regularly hovering around 40F (4.5C), and trees on the hillsides were rapidly turning a golden-yellow. It was time to push on from Libby, Montana, before fall turned into winter.

Most of the time, if you wanted to stay a step ahead of winter you would travel southward as fast as possible. And for several weeks before arriving in Libby, that’s what we had done. But now we faced a dilemma. If we continued cycling southward, we would be traveling through the Rocky Mountains where winter arrives much earlier, and with greater force. There was a high probability that we would be waylaid by bad weather if we continued on that route.

Instead, we decided to take a right turn and cycle almost due west. Our goal was to reach the Pacific Coast where the climate is generally more moderate, even in the dead of winter. But there was one potential problem. The Cascade Mountains - famous for their heavy winter snowfall - lay directly in our path. Winter would soon arrive in the higher elevations of the Cascades. In the past, the highway we planned to cycle across had closed due to snow as early as mid-October. Since it was already the start of October, our primary concern became biking over the Cascades before snow began to fall.

Following the Kootenay River

A thick layer of clouds hung low over the mountains as we pedaled westward out of Libby. It was not quite foggy, but there was enough moisture in the air that it almost felt like a drizzle at times. The dim light filtering through the clouds made it seem like the sun rose more slowly than usual.

Out on the road, we both noticed a big difference in our bikes. The shallow tread on our new tires rolled much more easily on the pavement than the knobbier tires they replaced. There also was noticeably less vibration in our handlebars. It felt like we could ride just a bit faster with the same level of effort - always a great feeling when you need to cover a lot of miles.

Our route followed the Kootenai River as it flowed westward. This is where the river reaches its southernmost point, before looping back northward towards Canada (where it empties into the Columbia River). After about an hour of cycling we arrived at one of the area’s most popular attractions, the Kootenai Falls, and decided to check it out.

The falls are accessed by taking a short trail from the road to the river. We don’t like leaving our loaded bicycles unattended, so we decided to take them with us down the trail. But about 2/3 of the way to the river, we ran into a problem. At that point, the land fell away down a steep embankment with a set of active railroad tracks at the bottom. The trail crossed high above the tracks on an enclosed bridge, then descended down four flights of stairs before continuing on a dirt path to the river’s edge. There was no way we were going to lug our loaded bikes down, and then back up those stairs.

We decided that PedalingGal would wait with the bikes at the bridge, while PedalingGuy went on to photograph the falls.

Waiting with the bikes at the top of the stairs. Kootenai Falls Park, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

But after viewing the falls, PedalingGuy encouraged PedalingGal to go see them as well. We locked the bikes at the top of the stairs, so that we could visited the falls together. We figured that the bikes were probably safer there than if we had left them back at the parking lot, since no reasonable person would want to haul the bikes up the hill we had just come down. Unfortunately, that same hill awaited us upon our return.

The falls turned out to be quite picturesque. The Kootenai River plunges about 60 ft (17 m) over a series of cascades where the channel enters a narrow canyon. When we visited, there was a high volume of water churning through the ravine. The roar of the rushing water and billowing waves of foam were impressive, and we stood on the shoreline mesmerized by the swirling currents for quite a while.

Admiring the cascading water at Kootenai Falls. Kootenai Falls Park, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Apparently the currents are dangerous as well. A sign along the path warned visitors to be careful, and noted that a number of people have lost their lives in the water here.

After viewing the falls from the shore, we walked to the park’s second big attraction, a swinging bridge over the gorge. The path near the water was lined with snowberry bushes, laden with their striking, white berries. We enjoyed walking out onto the bridge over the canyon. The view of the river from the swinging bridge was beautiful.

Soaking up the view of the Kootenai River as it rushes through a canyon below the swinging bridge. Kootenai Falls Park, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

By the time we made it back to the main road, the sun was finally starting to break through the thick layer of clouds. So as we pedaled up the road, we were treated to the sight of the Kootenai River below us, reflecting the fresh, blue light of the clearing sky.

As the gray clouds of the morning lifted, the Kootenai River turned a dazzling, azure blue in the sunlight. Kootenai River Park, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Back in Familiar Territory

It wasn’t long before we reached a familiar intersection. For most of the rest of the day we would pedal through countryside that we had visited while cycling the Western Wildlands Bikepacking Route (WWR) in June 2021. Of course, the WWR spent most of the time on dirt roads, rather than the pavement that we were on now. But roughly 20 miles of today’s ride would be on exactly the same route that we had traveled just over a year ago.

Bracken fern, turning yellow with the changing season, formed dense thickets along our route. Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We stopped at an intersection where last year we had taken a rough dirt road up into the Cabinet Mountains. Back then it had taken us two full days to go up and over the pass we would now cycle around in a single day. It’s great to be able to cover more miles on the pavement, but we wouldn’t trade anything for the memories we gained by cycling over those remote, dirt passes on the WWR.

This sign marked the intersection where last year we had turned onto a rugged forest road, up and over the Cabinet Mountains. That was an epic ride. But today we would stick with the pavement. Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Near the end of the day we stopped for dinner at a roadside pizzeria. It’s a new business, replacing an old deli and general store that had been closed when we passed by last year. For hungry cyclists, this was definitely an upgrade.

From the pizzeria it was a short jaunt to a campground run by the US Forest Service. After pitching our tent, we went for a walk along the Cabinet Gorge Reservoir. We watched the evening light fade over the water, while several folks fished along the shore.

As we were resting on some rocks near a dock, we were surprised to see a small bat flutter slowly by, not far above our heads. It was moving pretty slowly, not darting swiftly around like most bats we’ve seen. We watched as it landed about 25 ft up (7.5 m), on the side of a nearby tree, then headed over to have a closer look.

At first the bat had bundled up into a little ball to rest, and we couldn’t get a very good look at it. It seemed cold and lethargic. Perhaps it was a young, juvenile bat that was still struggling to feed itself. We recognized the possibility that the bat might be ill, but it was quite far away from us so it didn’t seem to pose any danger. Then, the little bat stirred and looked around. It studied its surroundings for several minutes, and turned its face towards us. We watched it for quite a while, but it did not take flight again. As the light faded away, we headed back to our campsite.

This little bat (genus Myotis), flew low over our heads before landing on a nearby tree. Big Eddy Campground, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Crossing into Idaho

From the Big Eddy Campground, we cycled northwestward, following the Clark Fork River valley. For most of the day we cycled along hilly roads that wound through ranch lands, horse farms and woodlots. The foothills of surrounding mountain ranges marched along on either side of us.

This restored covered wagon was on display near the entrance to a farm. Clark Fork River Valley, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We witnessed some of the drama of nature when this red-tailed hawk caught a snake by the side of the road and carried it away. Clark Fork River Valley, Montana, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

About an hour into our ride we crossed into Idaho. There was no sign marking the border. We were only alerted to the change by the fact that the road signs suddenly had a different style. More significant for us was the change in time zone at the Montana-Idaho border. We were now on Pacific time, which set our clocks back an hour. Tomorrow sunrise would come at 6:45, instead of 7:45, and sunset would appear to arrive an hour earlier as well. That’s something we would have to keep in mind since we like to make camp before dark.

Information signs along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille gave us a chance to take a break from the busy highway, and enjoy the scenery. Lake Pend Oreille. Idaho, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Crossing into Washington State

It was misty the next morning when we left town via the lovely Sandpoint Byway Bike Trail. The bike path followed a long, picturesque bay which runs right through the heart of town. The banks were lined with boat houses, small boats, and homes that were reminiscent of New England - rather than the “Old West” motif that is so common in the American West.

Near the trendy downtown shopping area, we passed a covered bridge that housed a number of boutique shops, bistros, cafes, and artisan’s workshops. Inspired by the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, Italy, it’s the only marketplace on a bridge in the USA.

The Cedar Street Bridge Market’s red roof reflected in the still waters of Sand Creek as we cycled by. Sandpoint, Idaho, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

From Sandpoint, we rode out onto the Long Bridge, a 2-mile (3.2 km) long span across Lake Pend Oreille. Over the years there have actually been four bridges built on this spot. The first two bridges were made of wood, and at the time were billed as the longest wooden bridges in the world. But the northern winters were hard on the wooden structures, so a third bridge was built of concrete and steel. But eventually the heavy automobile use became too much for that bridge. So a fourth was constructed in 1981.

These days all car and truck traffic uses the fourth bridge. Fortunately for us, the third bridge was kept intact for use by cyclists and pedestrians. Because it was originally built for automobiles, it is really wide. There’s plenty of space for cyclists, runners, and strolling tourists to use it without bumping into each other.

They say that the view of Lake Pend Oreille and the surrounding mountains is spectacular from the Long Bridge. But we couldn’t tell. The heavy mist completely obscured any scenery as we cycled across. The visual effect of the fog was still pretty interesting. The gray waters of the lake faded away seamlessly into the hazy distance, making it seem like we were crossing a much bigger body of water - or even an ocean where the distant shore is too far away to be seen. Without the benefit of other scenery, we focused our attention more closely at hand and enjoyed the spectacle of hundreds of spider webs on the bridge shimmering with dew.

Cycling across the Long Bridge, a 2-mile long span across Lake Pend Oreille, in the morning mist. The fog was so heavy we couldn’t see the shoreline, and the lake seemed to go on forever. Idaho, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

On the far side of the bridge we had to detour off of the bike path because of construction along the road. Fortunately, the detour was pleasant as it wound its way through a residential area on the shore of the big lake. Along the way, we spotted a sign at a local business applauding the construction for getting rid of the potholes in the road. We could certainly appreciate that sentiment.

Wild turkeys continue to be really common along our route. Yesterday we saw at least three big flocks, and there were even more today. It seemed like every few miles we would see a flock of wild turkeys out feeding in a cut-over hayfield. Most of the flocks seemed to be composed of a few adult females and their many offspring.

A flock of wild turkeys darts across the road. Pend Oreille River Valley, Idaho, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We also had the pleasure of spotting a sleepy barred owl, resting on a branch along the side of the road. Pend Oreille River Valley, Idaho, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Foggy conditions dogged us throughout the first half of the day. When the route ascended onto a hill or ridge, we would break out of the mist and bask in some sunshine. But pretty soon the road would return to the water’s edge, which remained cloaked in the fog well into the afternoon. Mid-morning, we took an extended, roadside break in the sun. For the first time in a while, we got out our camp chairs and enjoyed a snack of bananas and gorp along a quiet backroad. It was rejuvenating.

For a bit of excitement, PedalingGal got the first puncture in the new Schwalbe G-One tires. She knew something was wrong when she heard an intermittent hissing sound as she labored up a hill. After checking the tire, it was pretty obvious what was wrong. A big staple had punctured her tire. We pulled out the staple and rotated the tire. Fortunately, the holes from the staple were very small, and the sealant seemed to close them up.

After a quick dinner in Oldtown, Idaho, we cycled for just a few minutes before we crossed the state line into Washington. Once again, our little backroad did not have a sign welcoming visitors to the state. The only thing that gave it away was the fact that the mile markers along the road suddenly re-started at “Mile 0.” If it hadn’t been for that, we wouldn’t have known where the border was.

There’s no “Welcome to Washington” sign along LeClerk Road. The only indication that you’ve crossed a state line is the fact that the mile markers suddenly re-started at zero. Washington-Idaho State Line, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

A bit further up the road there was a county historic site sign that noted the presence of the state line. But what really caught our eye here was a smaller sign that someone added on the right-hand signpost. Instead of just noting that the area was a wildlife crossing, it advised motorists to “Watch for Suicidal Deer.” It sounded like a good tip.

It’s not the big, brown sign that caught our eye. The smaller, yellow sign seemed to have a much more important message. Washington-Idaho State Line, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

From there it took us just about an hour to cycle to the Skookum Creek Campground, run by the state Dept. of Natural Resources (DNR). The DNR campgrounds in Washington are a particularly good deal for cyclists because they are free. Cars and RVs have to buy an annual parking pass to use the campgrounds, but bicycles are exempt. The sites are relatively primitive (no potable water, pit toilets). But they’re usually clean and well kept.

We settled into a lovely spot overlooking the creek. As we were getting ready for bed, a woman walked by our campsite and remarked that the temperature had gotten down to 39F last night (4C). So we prepped for another cold night in the tent. Just after twilight, a great-horned owl serenaded us for the evening.

Leaving the River Valleys, and Back into the Mountains

It was a very misty morning, and our tent was covered with dew. In fact, the mist was so thick that everything was wet. The dampness added to the harsh chill in the air. But it also gave the campground a lovely glow in the morning sun.

Packing up in the morning mist. Skookum Creek Campground, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

A soft-focus sunrise over Skookum Creek. Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2021 Pedals and Puffins.

For the first four hours of cycling we continued to follow the Pend Oreille River. It had been several days since we had begun following the big river valleys, and the landscape remained a pleasant mix of private woodlands, open hayfields, pastures, occasional homesteads, and intermittent towns.

Within the first half hour of cycling, we spotted a handsome bald eagle resting on a wooden piling in the river. The subtle shades of white, gray and brown gave the image an almost surreal look, like a painting meant to be hung in an austere, modern-decor room.

This bald eagle seems to instinctively know how regal it looks, perched on a wooden piling in the Pend Oreille River, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We had a bit of extra excitement along the way when we came upon a long section of road where they were painting new lines. At the start of the construction zone, a sign warned motorists that it was illegal to drive on the fresh paint! This meant that cars would have to squeeze between us and the line down the middle of the road. This was not reassuring. There was no shoulder on this road. Fortunately traffic was light. A couple of cars tried to squeeze by a bit too close for comfort. To give ourselves a break, we stopped periodically to just get off the road, and appreciate the views of the river.

As we neared the town of Ione, we crossed the river on a cheery, red bridge. The color was very unusual for a bridge, which made the crossing memorable. And speaking of cheery, someone had placed a smiling face by the side of the road. Things like that always brighten our day.

After some debate, we decided to cycle into the town of Ione for lunch, even though it would add some distance to our ride. It was the wise choice. The detour was just under a mile, and the supermarket had indoor seating where we could relax for a bit. The meal and the break gave both of us a boost.

That was a good thing, because shortly after departing from Ione, our route launched up a mountainside to climb out of the river valley. The ascent into the Selkirk Mountains was four miles long, and sections were pretty steep. It took us slightly more than an hour to cover those four miles. We were both worn out by the time we got to the top.

But the hard parts always end, and the remaining miles breezed by. It took us only about a half hour to cover the next six miles to the Beaver Lodge Resort. The “resort” offers the only services for many miles, and we had planned to grab dinner and possibly camp there. The store was not very well stocked, but we managed to put together a pretty good dinner of crackers, cheese, baked beans and some tuna packets. When you’re hungry, that’s all you need to hit the spot.

Camping was another matter. The resort had a dozen different pricing levels based on access to various amenities. We learned that the tent camping fee didn’t include use of the flush toilets and showers, or even the potable water. They all cost extra. It was quickly evident that the US Forest Service campground about a half mile down the road would be better. So we went there, instead.

After setting up camp we took a walk around the grounds. Along the shore of Gillette Lake, we stopped to view a memorial that was dedicated to a local hero. He had been an outdoorsman in the area, before losing his life in combat in Afghanistan. The memorial was very tastefully done. In addition to a plaque that told the man’s story, it included a small, but detailed, 3-D holographic image of him. The hologram made it possible to see what he looked like, in a way that seemed more personal than a simple photograph. It made a big impression on us.

The campground was billed as having potable water. So the next morning we used up a bunch of our water supply to make Ka’Chava (a powdered protein and fiber drink) for breakfast. But then we made a big tactical error. In anticipation of filling up with fresh water before departing, we both dumped out all of the remaining, old water in our drinking bottles.

When we went to use the campground’s water pump, no water came out. Not a drop. The Forest Service had turned off the water for the winter.

We each still had a bit of water left in a reserve bottle, but that didn’t leave us any room for error if we ended up getting delayed before reaching the next available water source.

As we were bemoaning our bad judgement, a woman emerged from a nearby RV and asked if we needed water. She was really sweet. We learned that she and her husband were heading home that day, and had water to spare. Gratefully, we accepted the offer. So she filled a 1 L bottle with water for each of us. It was just what we needed.

Cruising downhill toward the Columbia River, we finally left the Northern Rocky Mountains behind. We had been in that ecoregion for a whole month. But now we entered a landscape that was drier and a bit more open. We still saw a lot of logging trucks go by, but the forests felt airier, with patches of meadows and less dense undergrowth. This was the Okanogan Dry Forest.

The miles flew by. Over lunch in the town of Colville, we decided that we should try to go further for the day than we had originally planned. On the far side of the Columbia River (just a few miles away), we would begin a long, tough climb towards Sherman Pass - the highest point on our route to the Pacific Coast. Any of those uphill miles that we could cover today would shorten the big grind up to the top of the pass tomorrow. After considering our options, we set our sights on making it to a campground 10 mi (16.1 km) past our original goal.

Less than a mile before arriving at the campground we stopped at the Log Flume Heritage Site. Walking along the forested trails, we read about how the first logging company in the area used horses and log flumes to harvest trees. The flumes used water from a nearby creek to send cut logs nearly five miles down the mountainside to a sawmill on the Columbia River. Remnants of the original log flumes can still be seen among the new growth of forest.

A shadowy statue of a logger evokes the spirit of the men who once sent huge logs down the mountain via wooden log flumes. Log Flume Heritage Site, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Like the vast majority of US Forest Service campgrounds, Canyon Creek Campground used a self-registration kiosk to collect payment. It’s pretty straightforward - on arrival we look for the key information such as how much the fee costs, grab a payment envelope, and go look for a suitable tenting site. Sometimes the message boards are covered with a variety of miscellaneous signs, mostly reminding people about the campground rules. Other times there is hardly any information besides the list of fees. Only rarely is there any information about the natural history of the area.

Since we were now in the colder camping season, only two of the campsites at Canyon Creek were occupied, so we had quite a few options to choose from. Once we selected our site we put our payment in the envelope, tore off the receipt, and went to drop our payment in the “iron ranger” (an iron post with an envelope drop slot). In most campgrounds you then clip your receipt to a post near your campsite, marking it as occupied.

But this campground’s procedures assumed that everyone would be driving a car. The instructions said we should hang our receipt on our car’s rear view mirror. The paper even had a helpful loop designed to fit around the mirror’s stem. In an effort to comply, PedalingGuy hung the receipt on his brake lever. We figured that would suffice.

After dinner we went for a walk, but didn’t get very far because it started to get dark. The main thing we noticed was that a lot of the leaves were turning yellow and brown. Winter is coming.

Little America

The big event for the next day was the 15-mile climb over Sherman Pass in the Kettle Mountains. Even though we had already ascended nearly 1,000 ft (305 m) the day before, we still had another 3,800 ft (1,160 m) to go. It was going to take a while.

There was no grace period, either. The climbing started right out of the exit from the campground. Needless to say, we took any opportunity to stop and take a break.

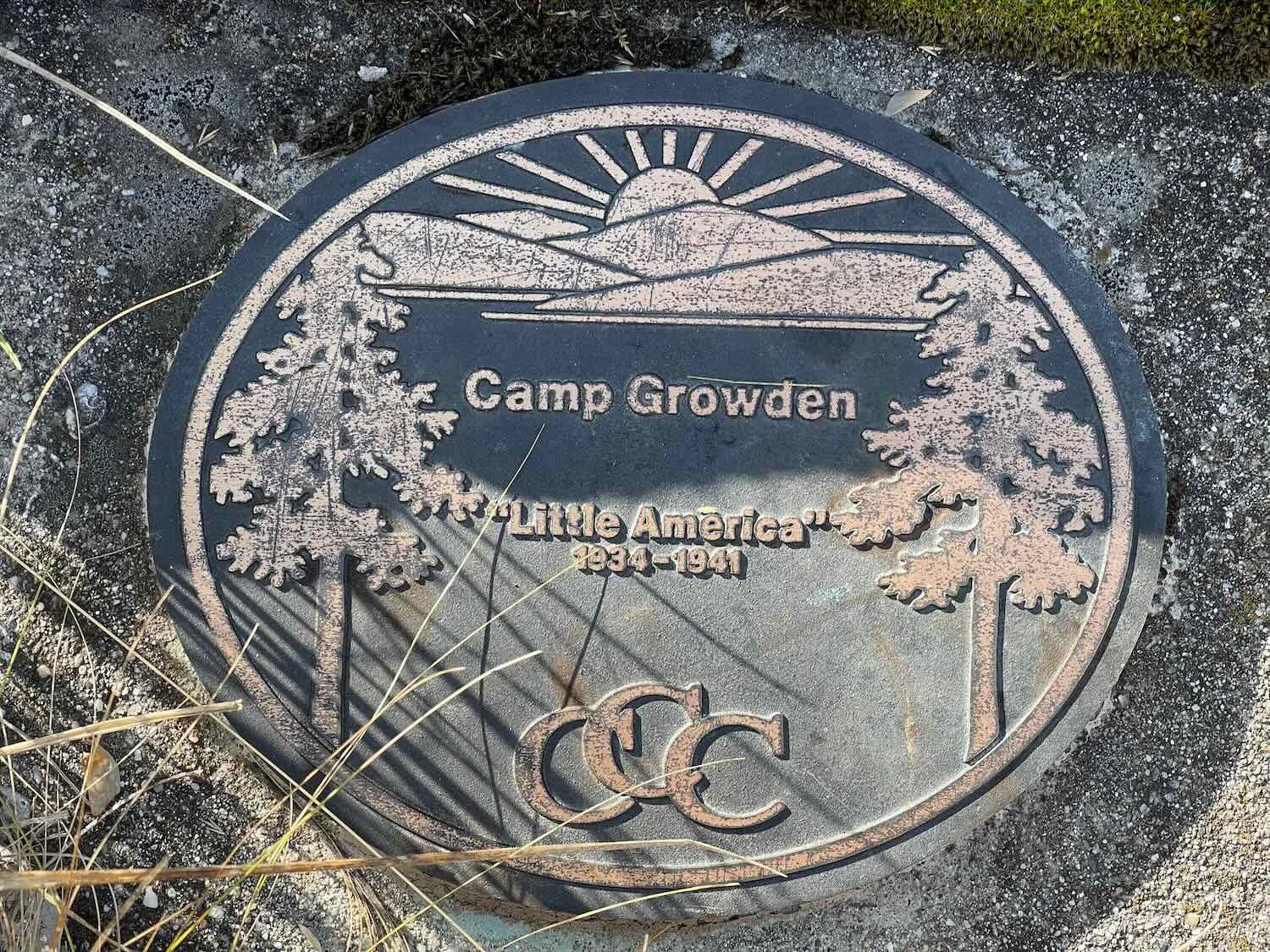

Just 3.5 miles up the road we stopped to check out the CCC Camp Growden Heritage Site. As one of the biggest Civilian Conservation Corps camps in the area, Camp Growden housed hundreds of men from all over the country - earning it the nickname ‘Little America.’ The interpretive signs at the heritage site were very informative. We particularly enjoyed reading excerpts from letters that the young men sent home to their families. During the Great Depression, these guys were grateful for the work, the meals, and the roof over their heads. Their legacy is a system of roads, trails and buildings, many of which are still used today.

Three and a half hours later, as we drew close to the top of the pass, we stopped at a scenic point overlooking a big bend in the road that skirted the edge of Sherman Canyon. Some of the steepest sections of the road (including a 16% grade) are found in the last two miles of the climb. So the vista stop came at the perfect time. We cycled out to the overlook on a paved path, and soaked up the view as we rested our tired legs.

A logging truck passes on the road below us at the Sherman Canyon overlook. Near Sherman Pass, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling on the path out to the Sherman Canyon overlook. Near Sherman Pass, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

A gray jay came by to see if we had any picnic snacks it could steal. Near Sherman Pass, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We finally reached the summit of Sherman Pass after nearly five hours on the road (including 3 hrs of cycling). Nothing beats the sense of accomplishment in reaching the top of a particularly big mountain pass.

That was a big climb. Sherman Pass marks the highest point on Highway 20 over the Cascades. Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

From the top of the pass, we sailed down the 14 miles (22.5 km) to the town of Republic in just over half an hour. The pavement was smooth and there was relatively little traffic, making for a fast and fun descent. At the bottom of the hill, we stopped at the first store we encountered to guzzle some chocolate milk and ice cream. Before long, we could feel the energy returning to our bodies.

We were delighted to see the “Welcome to Republic” sign as we passed a store on the way into town. Republic, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

There was a bit of confusion about our hotel reservation when we arrived in town, but in the end we settled into a big, quiet room at the Prospector Inn. Wifi was dismal throughout the town, but there was a strong cell signal that we could use in a pinch.

A Rest Day in the Old West

The town of Republic proudly retains its Old West character. Nearly all of the buildings along the town’s main thoroughfare are restored wood and brick structures from the early 1900s. Even the city hall is a log cabin that was originally built by the Civilian Conservation Corps as a ranger station. While taking a day off from cycling, we enjoyed a stroll among Republic’s old-fashioned storefronts. We were also amused to see that local wildlife regularly wander through town. Among the animals we saw were a mule deer ambling across the main street, and a flock of turkeys passing by the local auto repair shop.

Republic’s City Hall is a log cabin built in 1933 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Republic, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

This flock of wild turkeys wandered through town. Republic, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Into the Okanogan Highlands

Our ride from Republic to the town of Tonasket was another day filled with lucky breaks. As we left the hotel, we were each given a little Snickers chocolate bar by the hotel manager. That was a really sweet gesture, and we looked forward to having them as an energy-boosting snack out on the road.

Fall was now in full swing, and our route out of Republic was lined with the golden-yellow glow of the changing leaves.

Trees in full fall colors. Republic, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

The road out of town immediately began climbing towards the second big pass on our journey towards the sea. At 4,310 ft (1,314 m), Wauconda Pass would be considerably lower than Sherman Pass. But unlike Sherman, which was a pretty steady climb, the road to Wauconda Pass was quite hilly. As a result we benefitted from some downhills along the way to the top, but that made some of the uphills steeper. Even so, it was a lot easier getting to the top of Wauconda Pass.

But on our way up, disaster struck. At one of the rest stops, PedalingGal lost her Snickers bar. Now there are some things like major hills and cold rain that are difficult on a cycling trip, but losing a Snickers bar is devastating. However, when we reached the top of Wauconda Pass a small miracle happened. As PedalingGal reached into one of her panniers to get a jacket for the downhill ride, she discovered the missing Snickers bar. It had fallen out of her handlebar bag, and magically landed in one of her front panniers. She was elated, and promptly celebrated by eating the candy bar.

As we cruised down the far side of the pass, we entered a new region known as the Okanogan Highlands. Here, the dry forests gave way to wide open prairies and savannas. Forest-covered ridges were replaced by more gentle hills covered with tall grasses and sagebrush, populated with horses and cows. Rabbitbrush (a shrub we had last seen on the south rim of the Grand Canyon) bloomed along the roadsides. And stacks of hay bales as high as multi-story houses provided a bit of privacy when taking a roadside break. With the drier conditions, a sign reminded us of the danger of wildfires.

An old farm building in field of tall, golden grass. Okanogan Highlands, Washington, USA Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Taking shelter behind a wall of hay. Okanogan Highlands, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Our other bit of luck came on the final descent into the town of Tonasket. For a change, it really was all downhill into town (as opposed to what usually happens, where there’s a big uphill, right at the end). We sailed down a steep, 5% grade. And for the last five miles (8 km), we barely had to pedal at all.

The town of Tonasket is particularly friendly for cyclists. The visitor’s center has a tidy, enclosed, grassy area in the back that is designated for cyclist-only camping. Perks included a picnic table and access to an electrical outlet for charging our devices. We pitched our tent, and were delighted to discover that the wifi from the visitors center was blazingly fast - the best internet speeds we’d had in a really long time. It was a huge bonus after the painfully slow wifi in Republic. During an evening walk, we checked out some of the beautiful murals around town.

Our campsite behind the town visitor’s center. Tonasket, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Signs at the visitor’s center warned camping cyclists that lawn sprinklers would come on at 9am - a perfect way to prevent cyclists from overstaying their welcome. We had heard from others about the melee that occurs when waking up to lawn sprinklers. So the next morning we were a bit more motivated than usual to pack up all of our gear and leave camp as early as possible. We were up and out by 8am.

For 2.5 hrs we cycled on easy terrain through a valley filled with grasslands and farms. Low, sagebrush-covered mountains topped with rocky outcrops bordered the valley on both sides. There were very few trees. If we didn’t know better, we might have guessed that we were in Wyoming.

The route then passed through the more populated towns of Omak and Okanogan. Ten more miles passed quickly as we cycled through residential areas, past small-town businesses and city parks. This was our last chance for shopping before heading back into the mountains, so we stopped at the supermarket in Okanogan to fill up our water bottles and round out our food supplies.

A mural depicted a family of apple farmers, reflecting the region’s agricultural heritage. Okanogan, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

The unusual architecture of Okanogan City Hall was reminiscent of an old mission church. Okanogan, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Not long after departing from Okanogan, we hit the uphill stretch of road leading towards the next big mountain pass. For the next 7 miles (11.3 km) we slogged up a steep hill in the heat of the day. In fact, we hardly needed to have worried about snow just yet. The whole Pacific Northwest was experiencing above-average temperatures and unusually dry weather. We left Okanogan under sunny skies, with an afternoon high of 83F (28C) (the average high temperature for this time of year is 65F/18C). To make it up the hill, we stopped often to cool off in the shade.

In the lower foothills, our route was bordered by large groves of trees - which seemed out of place in the otherwise open landscape. We were cycling through some of Washington State’s famous apple orchards. Apples are the state’s most valuable agricultural product, with 60% of the country’s supply grown here. In fact, apples are so important that they were designated as Washington’s “state fruit” in 1989. Pedaling up the hill, we passed orchards labeled with the names of the varieties (gala, fuji, red delicious) being grown. There were farms with cherry trees as well. It was fun to see where all those apples come from.

But the orchards require a fair amount of water to operate, so they’re only grown in the lower foothills, close to the Okanogan River. Before long we left the apples behind, and continued our climb through golden-hued grasslands.

View back into the Okanogan River Valley, as we began our ascent toward Loup Loup Pass. Okanogan, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

After an especially steep ascent to enter our campground, we were relieved to finally arrive. We were both fatigued from the climbing and the heat. It felt awesome to rest our legs. We relaxed at a picnic table in the shade of the trees for a while before mustering the energy to pitch our tent.

Then we went for a walk along the lake. The air was very calm, allowing the still water of the lake to reflect the surrounding hills like a mirror. It seemed like the water levels in the lake (which is really a small reservoir) were pretty low. Many feet of rocks and mud below the high water line were exposed, creating a wide, rocky beach.

Fall colors reflected in the still waters of Leader Lake. Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Later in the evening, as we were preparing to turn in for the night, the full moon rose over the lake. There must have been some smoke in the air, because the moon shone with a vivid golden-orange color. We didn’t want to miss the moment, so we grabbed a camera and scrambled over to the lake in the near darkness. It was a beautiful way to end the day.

The flame-orange glow of the full moon reflected in the water of Leader Lake, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Once we were nestled inside our tent, a full chorus of barking dogs and yapping coyotes broke out. The dogs were far away, but the coyotes were much closer at hand, with calls coming from two different directions. We hoped the coyotes wouldn’t find our food, which we hadn’t tied up in a tree that night. All of the nearby trees were blackened at the base due to a fire, and we didn’t want our bear bags to get covered with soot. So we had tied them to a log fence in the campground, with the bags laying on the ground. Even if the coyotes couldn’t tear their way into the bags, they could do a lot of damage. We crossed our fingers and hoped for the best.

Then things got even more interesting. Just before bedtime, we both started smelling the very strong scent of a skunk. We hadn’t heard any nearby noises since the coyotes had quieted down, so we wondered whether a skunk had been attracted to our food bags. PedalingGuy took a flashlight and went out to check on our bags, but there was no sign of a skunk or any other animals. Meanwhile, the the smell was slowly starting to dissipate. Our best guess was that either a skunk had sprayed a potential predator nearby, or that one had been hit by a car out on the road in the valley. Regardless, we didn’t hear or see any skunks that night, so we were relieved.

The next morning dawned with a layer of high, thin clouds. We retrieved our, thankfully, intact food bags and hit the road. It was a perfect day for riding up a big mountain pass. We were surrounded by lovely ponderosa pine forests (one of our favorite habitats). Furthermore, the clouds kept the temperature comfortably cool all morning. Even though the climb was on the steeper side (6%-10%), we only had to stop and rest a couple of times.

We hardly broke a sweat on the ride up to the top of Loup Loup Pass. Okanogan National Forest, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Unfortunately, on the far side of the pass the air was much more smoky from some forest fires to our south. As the haze began to thicken, we realized that smoke was likely to be much more of a problem for us than snow on our ride across the Cascades.

The 12-mile (19 km) descent into the incredibly scenic Methow River Valley was a blast. The gradients on the downhill side of the pass were just as steep as the ascent had been, making for a very fast ride. With an average speed of over 20 mph (32 kph), we arrived in the valley in less than a half hour.

As we were leaving a supermarket after a hearty lunch, a woman named Masha stopped to talk with us. She now lived in the nearby town of Winthrop, but had done some cycling previously while living in Florida. We shared stories about cycling in the Florida Keys, and she asked a lot of questions about our trip. She said she had always dreamed of cycling the Pan-American Highway (from Alaska to Argentina), and invited us to stay with her and her husband for the night.

We had already planned to spend the night in Winthrop, so we decided to accept her offer. It turned out to be quite an adventure. The first inkling that this would not be a typical home visit came when Masha was giving us directions to her house. She mentioned several times that the house looks like a castle.

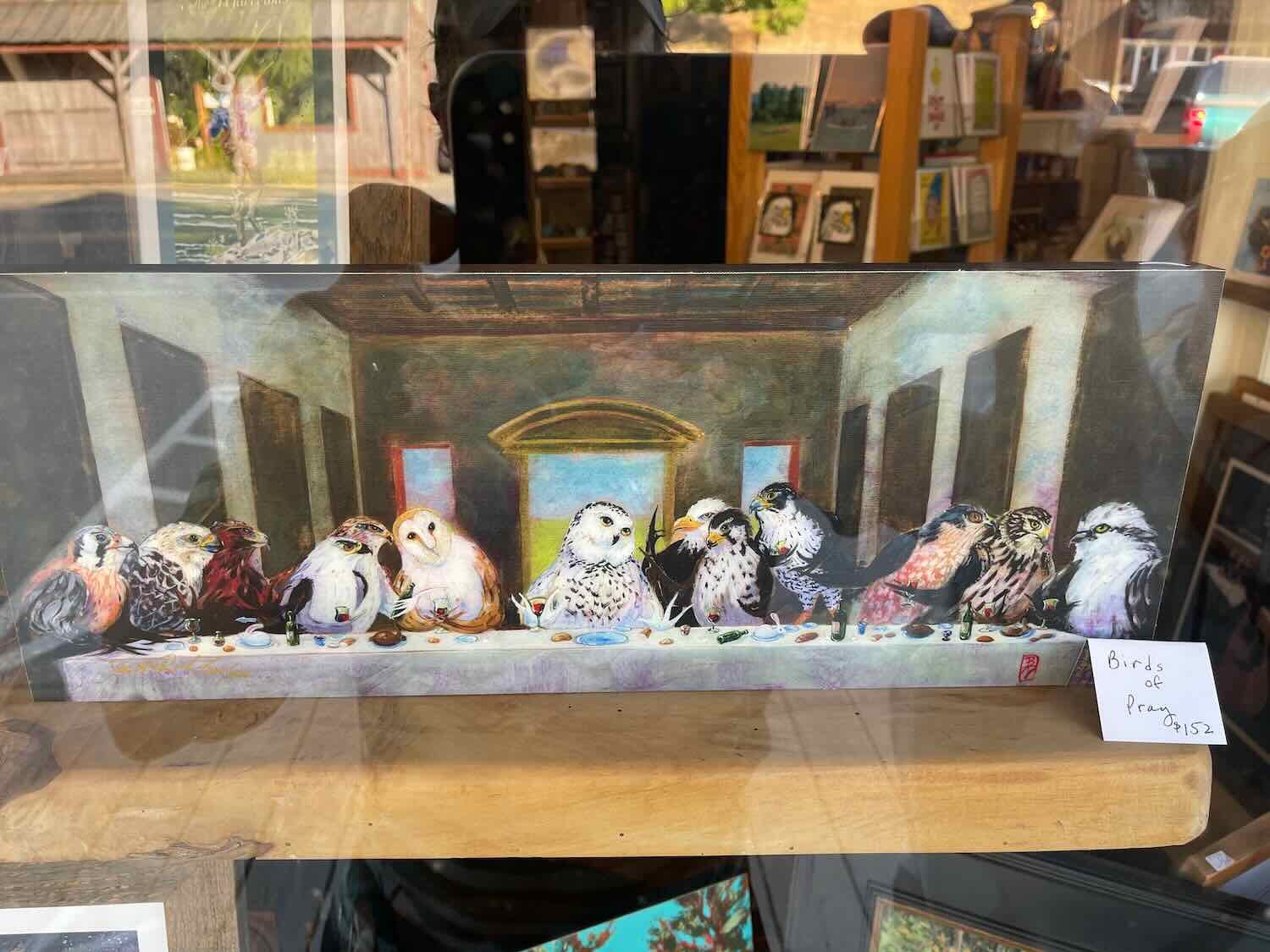

But Masha wouldn’t be home until 6:30pm, so we had some time to kill in the quaint town of Winthrop. All of the store-fronts in town have been restored to make it look like a 1900’s western town. We walked around the downtown shopping area, soaking up the Old West ambiance.

“Old West” storefronts in downtown Winthrop, Washington. USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Here are some more photos that capture some of the spirit of the town:

We also visited the local history museum, which had an extensive collection of items from the town’s mining and agricultural past.

A child-sized high-wheel bicycle at the local history museum. Winthrop, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

And, yes, when we arrived at Masha and Justin’s house we had to agree that it looks like a castle. In addition to turrets and towers, it even has a drawbridge over a small moat. Masha showed us to a room in one of the towers where we would spend the night. Then we visited with them over a delicious dinner of coconut soup with shrimp and mussels. We enjoyed learning about their interesting pursuits, and sharing stories about our ride. They were incredibly generous and welcoming hosts. It was a wonderfully memorable evening.

Our castle for the night, as we were guests in this unusual home. Winthrop, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Cycling Over the Cascade Mountains

The next morning we stopped at the Winthrop Store, where we had bought a few items the day before. We were warmly welcomed back by the proprietor, Keith. As we ate breakfast at a table in the back, Keith chatted with us for quite a while. Although many people pass through the store (including a lot of cyclists), he hadn’t met anyone before who was making the ride all the way to Patagonia. He said he was inspired by our plans. His life story was pretty interesting as well. He had worked for the US Forest Service for many years, and when he was transferred to Winthrop, he fell in love with the surrounding mountains. We could certainly relate to that. The Methow River Valley is very beautiful.

As we were heading out of town, we stopped to fill up our water bottles at a public fountain. There we got into another conversation with a friendly couple who were also getting water. They were from the San Juan Islands in western Washington, and were out for a trip in their camper. They knew about Ushuaia, Argentina, and we chatted with them for a long time as well - particularly about traveling in Baja, Mexico (where they had a lot of experience). In the end, we didn’t get a very early start on our ride.

We had a pleasant, but uneventful ride to the tiny town of Mazama (pop. 137). The smoke from the forest fires seemed to have cleared a bit, which was a relief. There was still a dull haze in the air, but we had expected it to be much worse.

In Mazama, we stopped at the general store and bought one of their famous sea salt baguettes that Masha and Justin had recommended. Topped with some garlic hummus, it was absolutely delicious. The baguette was huge, probably about a meter long. We were stuffed when we were done.

Savoring a sea salt baguette with hummus at the Mazama Store. Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

As we were prepping our bikes for departure from the store, we were approached by another former cyclist. John chatted with us for quite a while, asking about our bikes and our gear. We learned that in 2008 he and his wife had attempted to cycle from Bellingham, Washington (near the Canadian border) to Ushuaia. They also took the route down Baja. They made it as far as Guatemala, but then they had to abandon the trip. John was a great guy, and we really enjoyed talking with him.

Right out of Mazama the road started its ascent up to the next mountain pass, on the North Cascades Scenic Highway. We had decided to keep the day’s ride short, so that we could have as much time and energy as possible tomorrow to make it over two high, mountain passes before reaching the next campground. It was nice not to be in a hurry, and we took our time ascending into the mountain forests of the Cascades. Although we were in a national forest, and wild camping was theoretically an option, the highway passed through a steep-sided canyon that didn’t offer much hope for finding a flat spot big enough for our tent. So we stopped in the early afternoon at the Lone Fir Campground, with the beautiful Silver Star Mountain as a backdrop.

There were three notable characteristics of this campground. First, it was overrun with chipmunks. They were pretty tame, so we had to keep an eye on them (we worried that they might try to chew through our panniers). Second, there were many large tree stumps - remnants of a much older forest with bigger trees that had been cut down in the past. The huge size of the old stumps was a teaser for some of the big, old trees we would see later on along the coast. And third, the steep mountains that lined the valley cast very long shadows. By mid-afternoon, the sun was already disappearing behind the ridge, and it got quite cold.

The Lone Fir Campground has lots of big, old tree stumps scattered among the campsites. Okanogan National Forest, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

After finishing our evening chores, we went for a walk on a paved trail that headed out of the north side of the campground. We were surprised to see that there was a lot of damage to the trail where it crossed over a couple of creeks (including some bridges that had washed away). There must have been some flooding in the recent past. But the water was very low when we were there, barely covering the rocks in the stream bed. All of the surface water was beautifully clear. When the light in the forest became almost too dim to see, we turned around and headed back to camp.

Crossing a creek on a bridge made from a single, large log. The stairs leading up onto the bridge were etched out of another section of log. Lone Fir Campground, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We spent a quiet and peaceful night in our tent, but it was very cold. Even with all of our clothes bundled inside our sleeping bags, it was hard to stay warm. That made it tough to work up the motivation to get out of our sleeping bags in the morning. It was the kind of morning that totally chills your hands. Everything we touched seemed to steal warmth from our numb fingers.

Once we got going, it took us forever to cover the 6 miles (9.6 km) to the top of Washington Pass. Of course, part of the reason was that the road was steep. But a huge factor was that the air was very clear, providing stupendously beautiful views of the surrounding mountains. We stopped a gazillion times to take photos. Like many travelers on this scenic highway, we were particularly enthralled by the views of the Early Winters Spires - a majestic set of rock formations that tower over the road. The bright blue sky enhanced the views even more.

Ascending towards the Early Winters Spires on the North Cascades Scenic Highway. Okanogan National Forest, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

Near the top of the pass we stopped to enjoy a panoramic view back down the valley. We asked another tourist to take our photo, and he proceeded to take about 10 different photos, from different angles. He was very serious about getting a great photo for us. When we thanked him afterwards, he said that he didn’t speak any English, so we struck up a bit of a conversation in Spanish. We learned that he was originally from Honduras, but had been living in Mexico for the past 20 years. He was very friendly, and we had fun getting acquainted.

Approaching the top of Washington Pass, with the North Cascades Scenic Highway below. North Cascades National Park, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We finally reached the top of the pass around noon. And on the far side of the pass, we crossed over the famous Pacific Crest Trail, a hiking trail that runs north-to-south, from Canada to Mexico along the spine of the mountains.

From there we had another short, but strenuous climb over Rainy Pass, the final big pass of the Cascade Mountains. Then it was 20 miles (32 km) of downhill riding on an often-steep road. Flying down the mountainside at 20+ mph (32 kph), in the shadowy valley without direct sunlight, we struggled to stay warm. We could feel the humidity increasing with each passing mile as we descended deeper into the coastal rainforest zone. All the moisture in the air made it feel even colder. We bundled up in all the layers of clothing we could find.

There was also a striking change in the vegetation. The open ponderosa pine forest was replaced with dark, damp, moss-covered forests of Douglas fir, giant cedars and bigleaf maple, with an understory of vine maple. Many of the broad-leaved understory plants sported a dazzling array of fall colors.

Unfortunately, smoke from the forest fires increased dramatically as we descended into the valley. That made it hard to see any scenery more than a couple of hundred yards away. We didn’t stop at any of the overlooks because there wasn’t any point. We couldn’t see anything in the distance. Even worse, we could feel the smoke searing our lungs, so we didn’t want to linger any longer than necessary.

This sign along the road came a little bit late. We had long since descended into a thick cloud of smoke. North Cascades National Park, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We couldn’t enjoy the mountain scenery on our descent from Rainy Pass because smoke obscured our view. North Cascades National Park, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

A tunnel through a mountain ridge. North Cascades National Park, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

At the bottom of the descent, we finally took a break near the Gorge Power Station. Information at the site described how the power station had been built to supply electricity to Seattle, Washington. Three dams along the Skagit River send high-pressure water through mountain tunnels to run the power station’s turbines, supplying 20% of the power consumed by Seattle.

The Gorge Power Station. Ross Lake National Recreation Area, Cascade Mountains, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We had planned to spend the night at a national park service campground not far from the power station. But the smoke in the air was still very thick. So we decided to continue down the valley in hopes of reaching cleaner air. It was already late in the afternoon, so time was of the essence. We powered down the hill. Then finally, more than an hour later, we stopped at a modest RV park alongside the highway. It was nothing to get excited about, but we were the only people camping in the tent area, so we had a measure of privacy. Even better, the air was not quite as smoky here. For one night, it was okay.

Emerging from the Cascade Mountains

We had planned to ride the short distance to the town of Marblemount for breakfast. But on our way there, disaster struck. PedalingGuy had forgotten to tie up the loose ends on the ROK straps that held our food bag onto the top of his front bike rack. Cruising down the road, one of the straps got sucked into his front wheel, and within a split second had wrapped itself tightly around his front axel. He heard the noise of the strap as it jammed the wheel, and stopped as fast as he could. But it was too late. The ROK strap was wound tightly around the front axel, and the force of the spinning wheel had snapped the strap apart. We managed to get the strap unwound from the wheel, but it was unusable after that.

In addition, the massive force exerted on the strap bent the end of PedalingGuy’s steel front rack down towards his tire. He was incredibly lucky that the rack didn’t bend any further. There was still a quarter of an inch of clearance between his tire and the steel front end of the rack. But there was no way we were going to be able to bend the steel tubes back. We would have to buy him a new front rack as soon as we could arrange it.

When PedalingGuy accidentally got one of his luggage straps wrapped around the front axel on his bike while riding, the incredible force of the strap being pulled into the wheel bent his steel front rack down towards the tire. Here you can see the bent rack compared to a straight, new one (which we purchased later). Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

On top of all that, the accident damaged the magnet that detects the wheel rotations for PedalingGuy’s odometer. He re-seated the magnet on the front disk brake, but when he rode the bike, the odometer readings were way off - almost double the speed he was actually going. This was really discouraging, and not a great way to start the day. But at least the front wheel, spokes, brake and dynamo hub appeared to be okay. So we were able to proceed down the road.

When we arrived at the small store in the town of Marblemount for breakfast, we discovered that we were in luck. The store had a small hardware section, where we were able to buy a short bungee cord that would make a suitable replacement for the broken ROK strap. We also fiddled with the odometer, and pretty soon that seemed to be working again. Things were looking up.

About four hours into the ride, we stopped to view the big, old silos at the town of Concrete. Once part of a giant cement factory, the silos loom 100 ft (30.5 m) over the surrounding area. A sign at the base of the silos told the history of concrete production here, including the fact that the town had supplied the material to well-known places like Pearl Harbor and the Grand Coulee Dam, as well as most of the more local dams that provide hydropower to the city of Seattle. Interestingly, the words “Welcome to Concrete” painted on the silos are relatively new. They were put there for the filming of a Hollywood movie in 1993. Right from the beginning the words were painted in a way that made them look old and faded. Not everything is what it seems.

That tiny figure is PedalingGal at the base of huge cement silos. Concrete, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

An hour and a half before arriving in the oddly-named town of Sedro-Woolley, we hopped onto the Cascade Bike Trail. It was a nice change to cycle on the gravel and to be off the main highway. But it was also very dusty. Pretty soon, all our stuff was covered with a layer of fine dust.

Happy to be cycling on the peaceful (but dusty) Cascade Bike Trail, and getting a break from the highway traffic. Hamilton, Washington, USA. Copyright © 2019-2022 Pedals and Puffins.

We also left the Cascade Mountain Forests behind. The final 15 miles (24 km) of riding were nearly flat as we cruised across the Puget Lowlands - a broad, flat, coastal zone devoted to agriculture.

We ended up spending an uneventful rest day in Sedro-Woolley. For those wondering where the town got its name, Sedro and Woolley were rival, neighboring towns in the late 1800s. Sedro is said to have gotten its name as a mis-pronunciation of the Spanish word “cedra”, which means cedar. And Woolley was named after its town founder, Phillip Woolley. In 1989, the two towns set aside their rivalry and merged, but neither one was willing to give up its original name. Hence, Sedro-Woolley.

Upon our arrival on the western side of the Cascades, we had successfully beaten the winter snows. In fact, as mentioned above, we actually rode across the mountains in the throes of a serious heat wave. But just over two weeks later the road over Washington and Rainy Passes had its first snowfall closure of the season. And before three weeks had passed, the road was closed for the winter. We felt incredibly fortunate to have experienced the iconic North Cascades Scenic Highway with balmy temperatures, but relatively few other tourists. It was a fantastic time to be out in those mountains, and a part of our trip we will always remember.